MACAU:

TRIUMPH AND TRIBULATION

by Stuart Braga

Written at the request of Ed Rozario, President of the Casa de Macau Australia, this series of six essays outlines several aspects of the turbulent history of Macau over a period of four centuries.

They were first published in ‘Casa Down Under’ the newsletter of the Casa de Macau, Australia

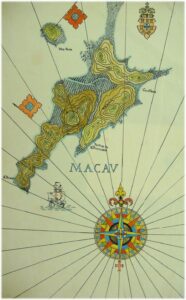

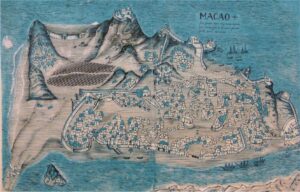

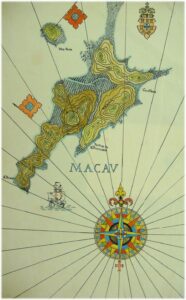

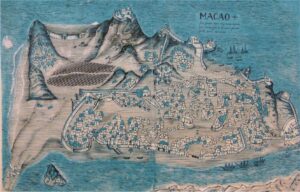

This is a reconstitution by Eugenio Beca. In the absence of any cartographic record of the original Portuguese presence in Macau in 1557, Jack Braga commissioned this map to indicate the location of the first Portuguese occupation: the Fortim de S. Francisco commanding the entrance to a protected bay and anchorage. A much rebuilt wall of this small fort survives in the modern city of Macau. Beca has provided embellishments in the manner of 16th century cartography: an elaborate compass rose, a caravelle and the Portuguese royal coat of arms.

Two flags are firmly planted in Macau and Green Island to indicate that the Portuguese were here to stay.

Part 1 — Conquest and Conciliation — the Portuguese come to Asia

A dramatised painting of the Battle of Diu, 1509, which established Portuguese naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean for the next 100 years.

Seeking a trade route to Asia, Portuguese seamen began to explore the west coast of Africa in the fifteenth century, at first cautiously, and then as they grew more familiar with ocean currents and remote coastlines, more boldly. By the end of the century, two great navigators had reached India, and commenced an era of Western influence in Asia that would change the world forever. Bartholomew Diaz rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488; a decade later, Vasco da Gama arrived at Calicut on the west coast of India. In the next twenty years, a string of some forty Portuguese forts dotted the coast of Africa and Asia as Portugal, a small country on the edge of Europe, established for half a century a commercial and strategic empire greater by far than any other power in Europe.

It was an amazing achievement, and it left its legacy for the next five centuries. The Portuguese occupation of Macau, which began in 1557, finally ended in 1999. Macau marked the furthest extent of the Portuguese empire. It was the first and last European colony in the Far East.

Colonial expansion is commonly the result of commercial prowess, often accompanied by religious zeal, sustained by overpowering military and naval force. This is broadly true of the astounding Portuguese conquests as they worked their way around the African coast and across the Indian Ocean between the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Francisco de Almeida who in 1506 was appointed the first Portuguese viceroy in the East, and his successor, Afonso de Albuquerque saw that to secure trade they must destroy any who might stand in their way. This they did in 1509 in the Battle of Diu, a major naval engagement off the Indian coast. At that time, the technological superiority of the Portuguese in shipbuilding and gunnery made it easy for Albuquerque to sweep his opponents from the seas. Arab dhows were no match for the far more manoeuvrable and better gunned Portuguese caravels and carracks.

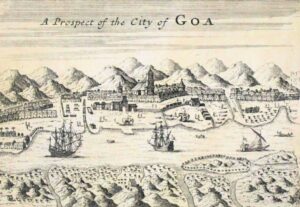

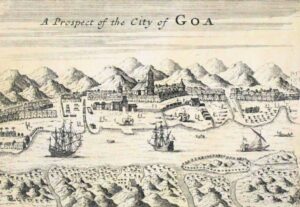

The next year, 1510, Albuquerque established a strong base at Goa on the west coast, held by a Muslim sultan. Albuquerque was a brilliant strategist, and with a much smaller force killed 6,000 of the 9,000 defenders. This, with two smaller domains, Diu and Damão, remained in Portuguese possession until 1961. The conquest was ruthless, bloody and swift. Portuguese religious and cultural superiority was at once asserted. Muslims were expelled and the practice of the Hindu religion was forbidden. Goa was seen as the springboard for the evangelisation of India in a remarkably militant way. It began with the establishment of numerous religious houses in Goa — convents, churches and seminaries. However, while Goa itself remained firmly Catholic, there was little impact beyond its boundaries. The impact of Portugal was in the long term demographic rather than religious. Some two thousand young men left Portugal each year to seek their fortune in India; few ever returned. Therefore Albuquerque encouraged inter-marriage with local women, thus beginning the long practice of racial integration that characterised Portuguese rule in sharp contrast to that of any other European empire.

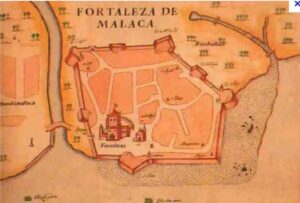

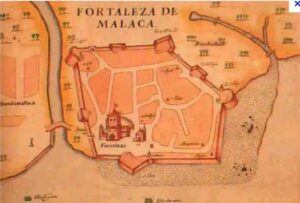

The next year, 1511, Albuquerque attacked Malacca, a strong position on the coast of Malaya, defended by a force of 20,000. Conquering it with a force of 900 Portuguese, 200 Hindu mercenaries and about eighteen ships, he set about at once to build a vast and very strong fort, which was intended to be impregnable, and was seen as such for more than a century.

This fort, A Famosa (the Famous), was the starting point of Portuguese expeditions to China and Japan in the following half-century. Facing the sea, Albuquerque constructed a huge four-storey stone keep, Torre de Menajem, the Tower of Homage, built in a style which modern artillery had rendered obsolete in Europe by the sixteenth century; in Malacca, it was intended to impress rather than to protect. It impressed local sultans who sought in vain to oust these foreign interlopers. 130 years later, in 1641, it took the Dutch nearly three years to drive the Portuguese from Malacca after a long and bitter siege.

Further east lay China. The Chinese were known in India, where the voyages of the celebrated Chinese admiral Cheng some fifty years earlier left a strong memory. The Chinese were seen by the Indians as a civilised people with paler skins than themselves, and Albuquerque decided to venture further east. When he arrived at Malacca in 1511, he found a fleet of Chinese junks there. He soon sent one of his captains, Jorge Álvares to find whether trade could be opened with these mysterious and remote people. The Portuguese engagement with China was about to begin, but this time, it would be by careful conciliation. There are no great naval battles, bloody conquests or extended sieges in the long history of Macau.

Part 2 — The great days of Macau, 1557-1640

The first Portuguese attempts to trade with China in the early 16th century ended in disaster when an embassy was despatched to the Imperial Court at Peking, led by Tomé Pires whose book Suma Oriental was an important reference work describing the Portuguese eastern discoveries. He seemed to be the ideal man for what proved to be an impossible task. After lengthy delays, the Chinese found that the communication to the Emperor which came, not from the King of Portugal, but his underling, the Viceroy at Goa, was not in the form of abject submission deemed proper for barbarian rulers. Pires and his entourage were seen as dangerous spies and were thrown into prison in Canton, where some were executed in 1524, while the rest died miserably some years later, still in prison. The Portuguese had discovered, as did other Europeans over the next three centuries, that dealing with the Chinese authorities was difficult, unpredictable, and could be dangerous.

This disaster halted Portuguese trade with China for a generation. Cautiously, others ventured back. It took some time to persuade the mandarins in Canton that the ‘Western barbarians’ (Portuguese) were not a threat, and that to do business with them was highly profitable for both the merchants and the mandarins. Business in the Far East has always depended on suitable gifts being made, and it is probable that the first Portuguese traders to arrive in the 1540s near Canton made sure that their presents were sufficient to gratify the mandarins. They sheltered and traded at several places before they found a small rocky peninsula at the mouth of the Pearl River with a sheltered harbour. Already well-known to the Chinese, this place was the location of a temple built in the late 15th century for the worship of the goddess A-ma. To the Portuguese the place became Ama-cao, eventually shortened to Macao or Macau. Within a few years a small settlement with a few mat sheds (temporary structures built of bamboo with rattan mats for walls) had grown up. In a few more years, this settlement had become far more permanent and costly, elaborate buildings had been erected.

How was this possible?

Macau and its merchants became, for about 70 years, the beneficiaries of a number of very favourable circumstances. The first of these was the decision made in the 14th century by the Ming emperors in China to forbid trade with the Japanese, who they contemptuously called ‘the dwarf barbarians’. The Japanese for their part made it punishable by death to leave Japan. This meant that these two Far Eastern empires developed in the next three centuries along divergent paths. In Japan, silver was relatively cheap; in China, whose currency system was based on silver, it became an increasingly precious metal as the population and economy grew under the stable administration of the Ming emperors.

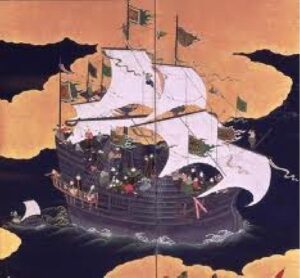

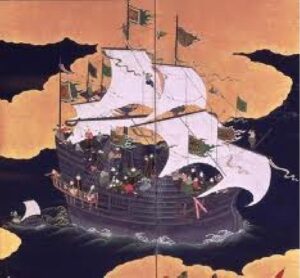

The second circumstance was the accidental discovery of Japan by the Portuguese. In 1542, Fernão Mendes Pinto and a companion who were trying to reach China were driven far north by a storm and reached Japan, where their arquebuses, early handguns, created a sensation. They were immediately copied by Japanese armourers. In the next thirty years, an amazingly profitable import/export business, referred to as the ‘carriage trade’, was set up, based on Macau. The Portuguese merchants found a ready market in Japan for Chinese silk, which commanded high prices, paid for in silver, by weight. Japan produced silk, but the Japanese much preferred Chinese silk, which was of better quality. Chinese silk was purchased in Canton for far less than it sold for in Japan. Seldom in human history can there been such a profitable trade, and for more than half a century until the early 17th century, the Portuguese held a monopoly of it.

In this period Macau became a boom town of fine houses, adorned with Chinese and Japanese furniture and art objects.1 They were inhabited by richly dressed people waited on by numerous black African slaves. People came from Portugal to enjoy the bonanza. According to Fr Manuel Teixeira, a population of about 500 in 1561 grew to about 850 by 1635.2 No-one bothered to count the slaves, but an American estimate made much later, in 1835, estimated the number then at 800-900.3 Some 10,000 Chinese people had come to Macau by 1635, but few if any would have regarded it as their native place (heung ha), and no-one bothered to count them either.

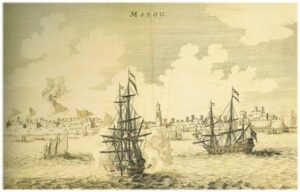

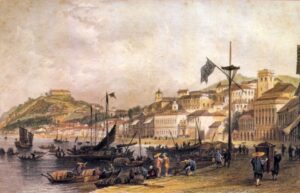

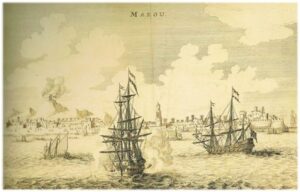

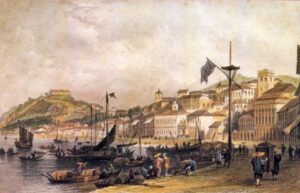

Looking westwards, with the Praya Grande in the left foreground.

J.M. Braga Pictures Collection, National Library of Australia.

Travellers to Macau in the early 17th century marvelled what they saw. FrAntónio Cardim, a Jesuit priest who lived there from 1632 to 1636, wrote:

Macao is put together of very fair buildings and is rich because of the commerce and traffic that are transacted there by night and day; it has noble and honourable citizens. In fact, it is held in great esteem throughout all the Orient, inasmuch that it is the depository of those goods using gold, silver, silks, pearls and other jewels; of all manner of drugs, spices and perfumes from China, Japan, Tonkin, Cochin China, Cambodia, Macassar, Solor; and above all, as it is the headquarters of Christendom in the East.’4

There were wealthy families who became patrons of the arts, ardent supporters of the Faith and contributors to the life of the community. They supported a charitable brotherhood, the Santa Casa de Misericórdia (the Holy House of Mercy) and religious institutions such as convents and orphanages. A municipal council, known as the Senado, was established as early as 1585. Soon there were three parish churches, St Lazarus (the oldest), St Anthony and St Lawrence. In 1575 a new diocese was set up, based on Macau. Initially, the bishop was Bishop of China and Japan, for this was a missionary diocese. A fine cathedral was built, generally known as Sé. The main religious orders, the Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinians soon arrived and set up missions. Each had its own church, dedicated to the appropriate saint, while the Jesuits, first in the field, built and then after a fire in 1602, rebuilt the great church which came to be known as St Paul’s. Besides these were two churches attached to the Santa Casa de Misericórdia and the Santa Clara Convent, and a chapel attached to the Jesuit seminary of Nossa Senhora de Amparo, where Chinese Christians were trained for missionary service in China. Besides all these was a small chapel attached to the Senate House. The presence of all these churches and chapels, and the sound of their bells, dominated Macau.5

If this great commercial and religious success seems too good to be true, it was. It all depended on two things: the continuing success of the hugely lucrative Portuguese monopoly of trade between China and Japan, and the willingness of the Chinese authorities in Canton to tolerate this wealthy place on their doorstep.

A warning of what was to come was the construction by the Chinese of a barrier wall between Macau and Chinese territory beyond in 1573, sixteen years after the first permanent Portuguese settlement. Portuguese were rarely allowed to go through its only door. Upon the door posts was a pointed inscription: ‘Dread our greatness; respect our virtue’. Events would prove that these were no idle words.

There was no warning in Macau of the establishment in 1600 of the English trading business,the Honourable East India Company and its counterpart the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) in 1602. Both were to have a sustained and ruthless entrepreneurial drive that the Portuguese lacked. Even worse was a violent anti-Christian reaction in Japan which began in 1614 and by 1639 led to the horrifyingly cruel martyrdom of many thousands of Japanese Christians and a bloody end to Portuguese trade with Japan. At the same time, the Dutch were taking most of the trade westwards, and there was a violet upheaval in China as the Ming dynasty was overthrown by the Manchus. With all of its trade cut off, Macau faced certain ruin.

Part 3 — ‘The Worm-like barbarians of Macau’

A century after the Portuguese navigator Fernão Mendes Pinto discovered Japan in 1542; Portuguese contact with Japan came to a sudden end. Henceforward, Japan was to be a closed kingdom for more than two hundred years. Only 160 years have passed since that long isolation ended. Hence the duration of Japan’s important role in the modern world is not as long as its period of isolation. What went wrong?

The first half century of Luso-Japanese contact had been amazingly successful. An immensely profitable trade developed, to the great satisfaction of both parties. Jesuit missionaries went to Japan together with the merchants and gained what seemed a miraculous success in the western Japanese island of Kyushu, where Nagasaki is situated. By 1580, 150,000 people had become Christians, and the number grew to about half a million by 1615. Several of the daimyo, the feudal lords who wielded immense power in Japan, were converted.

Emboldened by this rapid success, Fr. Alessandro Valignano, perhaps the greatest of the Jesuit leaders in the generation after Francis Xavier, sent a printing press to Nagasaki. It was used for some twenty years to produce devotional and evangelistic publications. However, the mission was, strange to say, too successful. The same was true of the trade, hugely lucrative for the merchants who came once a year on the Japan voyage to sell silk for silver, far more valuable in China than it was in Japan. The monopoly they enjoyed was too good to last, and by the end of the 16th century, Dutch merchants had arrived, prepared to go to any lengths to drive out the Portuguese.

Apart from a commerce that was far too one-sided, the impact of Christianity was viewed with alarm by Japan’s ruler, the Shogun, from his castle in Yedo, the city that is today Tokyo. For several centuries the Emperor in Kyoto had been a figurehead, while the Shogun, the head of Japan’s leading noble family effectively ruling Japan. In 1600 there was a bloody coup, with 40,000 men killed in the battle for power. Following this, the Tokugawa clan assumed power in Yedo. Naturally, the new Shogun regarded any other form of allegiance as a threat to his own authority and set out to destroy it. In this way of thinking, the rise of Christianity was seditious. It must be mercilessly crushed, lest there be a reversion to the two centuries of instability preceding the rise to power of the Tokugawa clan. The last ruler of Japan before the coup, Hideyoshi, then the first three Tokugawa shoguns, Ieyasu, Hidetada and Iemitsu cracked down with increasing severity. Hideyoshi forbade the preaching of Christianity, and in 1597 six foreign missionaries and twenty Japanese Christians were punished for defying the edict. Their ears and noses were cut off, and then they were crucified. These ‘Nagasaki Martyrs’, as they became known, were the first of a great number killed in the next four decades.

The Martyrs of Nagasaki, by an unknown artist, was cleaned, restored and repaired in London with the help of commercial donations. The picture, possibly by a Franciscan friar, dates from the 1600s and was formerly in the São Francisco Church (long since demolished) but is now kept in the Seminary of St Joseph.

Between 1614 and 1638 as progressively more severe policies were put into effect, Japanese Christians were wiped out in great numbers in a most cruel persecution concluding with a horrifying massacre in 1638 at Shimabara. This fortress held out for some time against the Shogun’s forces, and was eventually reduced with help from Dutch artillery. 37,000 rebels were then killed, many by being thrown over a cliff into the sulphurous boiling springs at Unzen. Many more Japanese Christians renounced their faith and reverted to their former religious practices. A tiny remnant clung to their faith in secret in villages near Nagasaki. The descendants of these ‘hidden Christians’ eventually emerged in 1865.

Until the Shimabara rebellion, the Portuguese were tolerated for the trade they brought, though when a ship arrived its rudder and armament were removed to ensure that its crew were helpless. It was an impossible situation, and the last two Portuguese galliots left Nagasaki in 1639, having been forbidden to trade. In vain the merchants begged, tears running down their cheeks, that they were innocent, and that ‘Macau gets nourishment from Japan, and if we are deprived of this trade we will all relapse into the utmost destitution. Immediately afterwards, the Shogun, Iemitsu, adopted a rigorous policy of excluding all foreigners except the Dutch, who were allowed to send one ship a year to Nagasaki where they were under close and humiliating supervision. Whereas the Japanese government had been curious and welcoming in the 1540s, a century later, in the hands of a new ruling family, it had become fearful and xenophobic. On 22 June 1636, even before the Shimabara revolt, Iemitsu issued what came to be known as the Closed Country Edict. It did not mince matters. It is quite lengthy, but the first three clauses set the tone for the other fifteen.

Part 4 — Hard times

For most of its first century, from the 1550s until 1640, Macau was prosperous, but most of the next two centuries were a bleak, poverty-stricken time. The Chinese magistrate on Heungshan island, of which Macau is a small part, exercised strict and rigid control, and the King of Portugal had insufficient strength to do anything to help his remotest colony.

There was only one straw to grasp at: the supremacy of the Portuguese Crown. Overshadowed by the Spanish in nearby Manila, the Portuguese in Macau clung doggedly to their separate identity after Portugal came under Spanish dominion from 1580 until 1640. During this time, Spanish kings left the remote, obstinate Portuguese outpost largely to its own devices. On the restoration of the Portuguese throne in 1640, the Macau Senate managed to send the new king, João IV, a gift of two hundred bronze guns, cast locally. King João, told of the tenacity of this tiny place at the remotest end of the earth, is said to have remarked wonderingly, não ha outra mais leal — ‘there is no other more loyal’. Shortly before his death in 1654, it was added to the city’s motto, and the Macau Council proudly bore the title Leal Senado, Loyal Senate, until 1999. It was a gesture that in reality meant little, because Macau was poverty-stricken, with a declining population, and left with little but a magnificent past upon which to dwell.

They go in a body with rods in their hands to the Mandarine who resides a League from hence and they petition him on their Knees. The Mandarine in his Answer writes thus: ‘This barbarous and brutal People desires such and such a thing: let it be granted.’ Or ‘refus’d them.’ Thus they return in great state to their City and their Fidalgos or Noblemen with the Badge of the Knighthood of the Order of Christ hanging at their Breasts have gone upon these errands … if their King knew of these things it is almost incredible that he should allow of them.’

This was indeed forbidden by King João V in 1712, but in Macau, far from the royal court, nothing changed. These impoverished and demoralised people were cut off from their distant homeland and royal authority. The mandarin ruled here. From grim necessity, the councillors developed a practice of cringing obsequiousness to the Chinese authorities at the Casa Branca and at the Chinese customs house within their very walls. They had to do so in order to survive. Navarrete’s Spanish view, hostile to the Portuguese, was that the people of Manila were free, but that the people of Macau were slaves to the Chinese. They were indeed trapped in a most unenviable situation, wracked by penury, and with no way out. Even if ships could be found to take them away, where would they go, and how would they evade Dutch control of the Straits of Malacca?

Nevertheless, through all of this period of some two centuries, despite the severe restrictions which they endured for so long, the Portuguese community of Macau continued to show an amazing degree of stubborn endurance. They are qualities that have lasted right to the present day, for we are the heirs of their persistence.

Part 5 — Struggle for survival

Things did get better, but only very slowly. The improvement could have been much greater but for several poor decisions. In the late seventeenth century, Jesuit influence grew at the Emperor’s court in Peking, chiefly through the outstanding Jesuit astronomer, Fr Verbiest, who won the confidence of the Kangxi Emperor to such an extent that in 1685, he decreed that Chinese ports were to be opened to foreign shipping. This should have been a golden opportunity for Macau to recover much of its former status, but the opportunity to take it up slipped through the fingers of the Macau Senate, which viewed the imperial edict with resentment and suspicion. They saw it as depriving them of the monopoly rights of trade with Canton that Macau had under the Ming dynasty before it fell in the 1640s.

The emperor under-estimated the importance that foreign trade would come to have, but it began in a small way. Some control was needed, so in 1719 the Kangxi emperor, towards the end of his reign, again proposed to centre all the foreign trade of China at Macau. Incredibly, the imperial offer was once more rejected, seen as a ‘Trojan horse’, giving the Chinese a much larger presence in and control of Macau than they already had. The Senate baulked at he cost of having to provide fifty to sixty officials to administer the proposal. Perhaps the rejection was not as blinkered as it might have seemed. The Senate had seen too many instances of local mandarins squeezing all the money they could from any profitable operations undertaken by the Portuguese. Yet gradually they changed their view, but it was too late. In 1732, thirteen years later, the Yongzheng emperor renewed the proposal. This time the Senate was enthusiastic.

However, the Bishop of Macau was not, as it would bring English traders, Protestant heretics, into the City of the Name of God. Although foreigners were not permitted to reside in Macau, several had slipped in as ‘lodgers’. Most were bachelors, and the effect on Macau’s night life was predictable; these men were not monks. Fearful for the morals of his flock, the bishop persuaded the Viceroy of India, Pedro Mascarenhas, to over-ride the Senates wishes. In vain the Senate protested.

For the third time, Macau’s chance of economic recovery was pushed aside, this time by the overriding authority of the Viceroy in Goa. Meanwhile, British merchants were taking a growing interest in trade with China. They dealt chiefly in tea, oriental curios and porcelain, which became known in Britain as ‘china’. Opium came later. Their ships were larger, and already it was clear that the shallow water around Macau was hazardous for navigation. Following the Viceroy’s ban, the British went to the nearby island of Lintin in the Pearl River estuary to bargain with Chinese merchants instead of calling at Macau.

In the mid-eighteenth century, the steady growth of foreign trade led to a Chinese reconsideration of the basis on which it was conducted. Only in Canton was the administrative machinery sufficiently well developed to regulate trade and traders on both sides. In 1760, all ports were therefore again closed except Canton, and a set of eight regulations issued governing trade. As usual, the prohibitions these contained were negotiable by the time-honoured means of ‘squeeze’. However, in one case there was no room for compromise. No foreign women were permitted in Canton, and foreigners were permitted to reside there only during the trading season, confined to a small area outside the walled city. The reason was obvious. The Chinese knew that permanent residency of foreigners of both sexes would create another European colony.

This created an immediate problem for nearby Macau, which had not long before banned foreign, i.e. Protestant, residence. If Macau continued to exclude foreign residents, they were likely to force their way in. If so, the Chinese were unlikely to stop them, because it was convenient to have them close at hand, but not within the camp. For the Senate, a pragmatic solution was vital lest Macau lose all its trade. So the ban was lifted, despite the objections of the bishop; foreigners might live in Macau, but they were not permitted to own property.

The Senate was right in supposing that this step was essential to the survival of Macau. Many years later, an English army officer observed, ‘the English merchants only rent houses here, but since they have been forced to retire from Canton and to reside in this place, Macao has risen from an almost ruined to a very flourishing condition. The Portuguese as well as the Chinese thrive on British wealth and industry.’ Poverty that had ground down the Macanese for generations began to ease, chiefly through the vigorous enterprise of the newcomers, especially the East India Company. This huge mercantile company was the worlds first multi-national corporation. Its business was effectively globalised three centuries before the term existed.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, trade in opium was insignificant, but it was growing in value and the number of addicts in the Canton area was also growing. Recognising opium to be a dangerous drug, the Yongzheng Emperor prohibited its importation in 1729. As usual, this prohibition was seen in Canton as no more than yet another opportunity for extracting ‘squeeze from foreign merchants, and the imperial ban was quietly ignored. At that time, no-one could have foreseen that the insatiable Chinese demand for opium and the vastly increased supply of it from India would eventually lead to war between Britain and China.

From the late eighteenth century, the illegal trade flourished and after 1833, when the East India Company withdrew from the China trade, it boomed in the hands of unscrupulous private traders such as Jardine and Matheson. The consequences were disastrous for China, but in the short term led to the triumph of British commercial and strategic power in the Far East. The Opium War broke out in 1839, and the Chinese were humiliated. Their ports were thrown open for trade and in 1841 Hong Kong was occupied by the British, who ruled it until 1997.

Indirectly, the consequences were also disastrous for Macau and its people. Within a few years the British and other foreign merchants left Macau, whose economy all but collapsed. An English journalist in Hong Kong wrote in 1844: ‘We have before us a most melancholy account of the deplorable state of affairs in Macao. The Government are literally bankrupt. Not a stiver to pay a few miserable half starved troops … We hear that since April the exchequer has been empty, — the troops threaten that they will stand it no longer and a riot is far from improbable. (William Tarrant, Hongkong, 1839 to 1844, p. 144.) It did not come to this, but the situation was indeed grim.

In the following decades, many Portuguese youths left Macau for better opportunities in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Japan and other locations throughout the Far East. Perhaps the lowest point was the Great Typhoon in September 1874, which devastated Macau, leaving at least 2,000 dead. In the next few months several hundred people fled to Hong Kong from Macau. Its historian, Carlos Montalto de Jesus, sadly commented that ‘the disastrous typhoon consummated the ruin of the Macanese’ (Historic Macao, p. 429).

A few nostalgic émigrés would sometimes return at weekends. A modern vignette by Amadeu Gomes de Araújo of their impressions gives some understanding of the sleepy backwater that Macau became in a chapter Caminhos Cruzados (‘Crusaders Paths’) of his book Diálogos em Bronze: memórias de Macau:

In the lobby of the Hing Kee Hotel, the aroma of jasmine tea added pleasantly to the murmur of that Sunday morning. The space was ample and comfortable, devoid of luxury. Around the small rosewood tables where teapots were steaming, portly weekend clients reclined on worn Victorian sofas and armchairs, speaking in English. The majority, who had arrived the night before, came from Hong Kong and Canton to drink and play fantan, a Chinese betting game. In their conversation, which was always animated, they invariably contrasted the decline of old Macau, with no port or infrastructure, with the charm and wealth of the young and vibrant Hong Kong.’

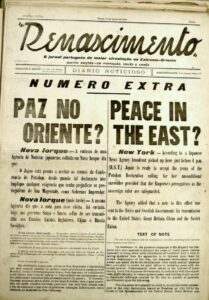

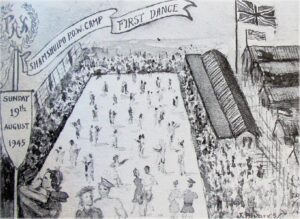

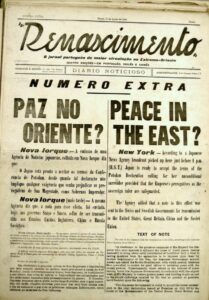

It would take another half century before things changed. Then they changed radically. The Japanese Occupation during World War II reversed the flight of refugees as perhaps 200,000 people, mostly Chinese, but including more than 90% of the Portuguese population of Hong Kong, fled to Macau. This was a period which the English writer, Austin Coates, described as ‘Macau’s finest hour’.

Part 6 — Macau’s finest hour

Hong Kong fell to the Japanese on Christmas Day 1941. There was a Japanese victory parade, but few came to watch it. Two who did were Francis Ozorio and his brother Charles, boys of eleven and eight, who cowered at the roadside as the Japanese troops marched past. ‘We were bloody terrified,’ said Francis. Their heads bowed low, they were amazed to see that these soldiers who had defeated the British Army were shod with cheap shoes with canvas uppers. Their lack of good equipment had not stood in the way of a victory that brought Hong Kong to its knees.

Francisco (‘Frank’) Soares, the Acting Portuguese Consul, had already grasped the situation firmly, and realised that the broadest possible definition would have to be given to nossa gente, our people. In practical terms, this meant the granting of Portuguese citizenship to hundreds of people who had hitherto claimed to be British. This would enable them to obtain Third National [i.e. neutral countries] passes from the Japanese authorities. This later created criticism, it being said that he granted papers to people whose only claim to have anything Portuguese in them lay in that they had eaten Portuguese sardines. They now clamoured for Portuguese Identity Cards, wore arm-bands bearing the Portuguese colours and sought refuge in Macau. 12

Soares issued some 600 certificates of Portuguese nationality.13 Without doubt this action saved lives; he was Hong Kong’s Schindler. His grandson, Bosco Correa, explained what occurred. ‘When the Japanese attacked Hong Kong on 8 December 1941 my grandfather, then 74 years of age, was the Acting Consul for Portugal. He decided to move the Consulate from the Bank of East Asia Building in Des Voeux Road, Central, to his home in Homantin. When Kowloon was abandoned a few days later by the British forces who fell back to Hong Kong Island, looters took over Kowloon and he opened his home and gave refuge to some 400 refugees, mainly Portuguese residents from Homantin and Kowloon Tong.’14

The Portuguese community was in some ways even worse off than the British, who were at least given scanty rations by their captors in internment camps. Portuguese civilians were not. Those paid weekly would have received their last pay on Saturday 6 December; those paid monthly, at the end of November. Poorly paid clerks living a hand-to- mouth existence were in dire straits, and there was real distress, though not on the scale of the afflicted Chinese working class. Poor Chinese died of starvation by the hundreds every day’. William Vallesuk, Chief Radio Engineer of China Electric Co. Ltd, described the harrowing situation.

‘Never, as long as I live, will I forget the scenes of horror, of inhuman suffering, that I have witnessed. People dying by hundreds in the streets; mothers — themselves on the doorsteps of death — wailing over corpses of their infants; a child of six beheaded in the middle of the street — bullets are too precious to waste — for snatching a handful of rice from a military canteen; women and old men slowly tortured — until they begged for death — for forgetting to bow to a sentry. To a man accustomed to a normal, routine mode of living, these things will sound incredible, unbelievable — yet they happened, and what’s more, I’ve seen them happen with my own eyes’.15

The Macau government quickly came to appreciate the grave situation of nossa gente in Hong Kong. A trickle of refugees began in the motor trawler Perda as early as 10 December, the third day of fighting. After the surrender it became a flood. Arrangements were made for a ship-load of refugees to go to Macau on 8 February 1942 in the Shirogane Maru. These were people without work or resources. They arrived in Macau destitute and starving.

Pinky da Silva was on the ship. He wrote his recollections some years ago. ‘About 250 plus Hong Kong Macanese assembled at the Blue Funnel Line Holt Wharf at Tsimshatsui, Kowloon. About mid-morning we boarded the ferry which used to ply in Japan’s Inland Sea and was commandeered to serve in the Imperial Japanese Navy. All the officers and crew members wore Japanese naval dark winter uniforms. Canvas awnings shrouded the whole deck but I was able to peer through a viewing space on the starboard side throughout the 4 or 5 hour voyage to Macau.

It was a miserable February day of light drizzle. We arrived in the afternoon at Ponte 16, at the end of Avenida Almeida Ribeiro and close to the Kwock Chai Hotel, then one of Macau’s tallest buildings. After an hour or two of paper work and arrangement we (I guess the whole assemblage) proceeded to Colegio de Dom Bosco (opposite Igreja de Sao Lourenço) for a hot meal of well-received fish conjee. Meanwhile, Macau families were waiting outside to greet and embrace their Hong Kong Macanese comterraneos.

At this juncture certain groups were allotted to stay at selected places such as Velho Amazem, Casa Luso-Chinesa (near Igreja de Sao Augustinho), Tung Hoi (an abandoned ferry boat), Fat Chee Kee (a housing project) and so on. I was already tired when my family proceeded to Gremio Militar (now Clube Militar). We bunked there with some others for about three days when Leo de Almada e Castro and Jack Braga arrived and selected certain families to go to Hotel Bela Vista which was to become the premier refugee center. Bela Vista Refugee Center as it was then called had a spacious kitchen as befitting a hotel geared for large dinners. The Bela Vista Refugee Center Kitchen cooked and provided meals to about two or three other refugee centers daily.’ There was another shipload of 616 on 20 April and a steady flow for the next three years.

Leo d’Almada, the outstanding leader of the Hong Kong Portuguese community, called Macau ‘the miracle of the time’. 16 Later, borrowing Churchil’s famous phrase, Austin Coates referred to the war years as ‘Macau’s finest hour’. 17 Both comments were just. Governor Gabriel Teixeira did not need to go out of his way to provide a safe haven for so many refugees. In making them publicly welcome, and in making available every possible public building for their accommodation, he established the merciful policy that his administration then pursued until the end of the war. Teixeira could easily have taken the view that Macau had already done enough, and that public services were stretched to breaking point as it was. He could have concluded that the Japanese had created this problem by occupying Hong Kong, planning for it to become the regional centre of their grand design, the ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’. Let them show what they could do, and harness the capabilities of the people they had inherited.

Perhaps the strongest reason not to accept Portuguese refugees from Hong Kong was that they or their forebears had turned their backs on Macau. If Macau meant so little to them then, why should Macau lift a finger for them now? If any of these considerations crossed Teixeira’s mind, he quickly dismissed them. The disaster in Hong Kong had precipitated a massive humanitarian crisis. In the three and a half years of the Japanese Occupation, thousands of people fled to Macau, most of them taking with them little more than what they could carry. Austin Coates, a writer with a close knowledge of and interest in Macau, wrote of this period in generous terms.

‘The whole of the gambling taxes — $2,000,000 — were made over by the government to the assistance of refugees. Indeed Macao’s entire conduct during the period from Christmas 1941 to August 1945, when Hongkong was under Japanese occupation, was a gesture of unselfish friendship, made in Portugal’s traditional style, regardless of dangers which others less magnanimous might have thought it more prudent to avoid. The patient endurance of the Macanese during these fateful years, and the sagacity and foresight of their Governor can hardly be overestimated … no one who experienced Macao’s hospitality during these years would ever forget it. The entire episode ranks as one of the city’s finest moments’.18

The bairro had row upon row of single-storey huts, each with one room and a tiny kitchen. Measuring no more than 20 by 20 feet in total area, each hut had a packed earth floor, a tile roof, a high Chinese style cement threshold you had to step over, and no plumbing. The hut’s two windows had no glass panes: they were just barred with wood strips, and on the outside were plain wooden shutters.’

Jorge Remédios, UMA Bulletin, 1999

According to Jack Braga, almost ten thousand of Hong Kong’s Portuguese population fled to Macau. Many were able to claim British nationality and sought assistance from the British consul, John Reeves. Initially appointed as vice-consul in what was for the British Foreign Office a remote and insignificant outpost, this young diplomat became a key man between 1942 and 1945. It was John Reeves’ responsibility to assist in the care of the thousands of refugees as best he could. Reeves had been sent to Macau shortly before the outbreak of war for a ‘rest cure’ from Mukden, in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, a forbidding place at the best of times. Some rest cure! At the British consulate in Macau flew the Union Jack, the only Allied flag between India and Alaska, apart from the embassies in Chungking. It was a beacon of hope for desperate people. The British government agreed to pay its citizens a small subsidy. Theresa Yvanovich da Luz wrote that ‘dependants of each Hong Kong Portuguese in prisoner of war camps received 30 patacas a month from the British Consulate and rations from the Macau Government like oil, rice and bread. That did not buy very much as food was scarce and expensive.’19 This matched the Macau government’s subsidy to other Portuguese refugees, but was much lower than the $120 subsidy paid to British subjects.

The cost of food steadily increased as the war dragged on. By the end of 1943, it was, according to Paul Braga, 20 to 60 times its pre-war rate. He went on: ‘the effect this malnutrition has on people in Occupied parts is indescribable. With the exception of those who work with or for the Nips, practically everyone has a colourless, parchment-like skin. Each has that drawn expression of constant strain and worry, and hardly without exception, they are very considerably underweight.’20 Every day for three years and eight months was a day of gnawing hunger. Even the fabulously wealthy Sir Robert Ho Tung, who had also fled to Macau, ran short of funds. However, while in Macau there might be privation, in Hong Kong there was fear, mass starvation, constant brutality and sudden, violent death.

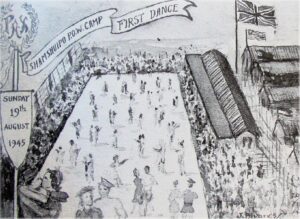

Macau soon returned to its peaceful pre-war condition. All of the British and most of the Portuguese refugees returned to Hong Kong as soon as it was in a fit state to have them back. Jack wrote in March 1946 that ‘things get quieter and quieter in Macao, with so many less people living here’.24 It would take another generation, and the dawn of prosperity in China to bring back to Macau the abundant wealth she had known in her earliest days.

MACAU:

TRIUMPH AND TRIBULATION

by Stuart Braga

Escrita a pedido de Ed Rozario, Presidente da Casa de Macau Austrália, esta série de seis ensaios descreve vários aspetos da turbulenta história de Macau ao longo de quatro séculos.

Os ensaios foram publicados pela primeira vez na “Casa Down Under”, o boletim informativo da Casa de Macau, Austrália.

© Stuart Braga 2013

This is a reconstitution by Eugenio Beca. In the absence of any cartographic record of the original Portuguese presence in Macau in 1557, Jack Braga commissioned this map to indicate the location of the first Portuguese occupation: the Fortim de S. Francisco commanding the entrance to a protected bay and anchorage. A much rebuilt wall of this small fort survives in the modern city of Macau. Beca has provided embellishments in the manner of 16th century cartography: an elaborate compass rose, a caravelle and the Portuguese royal coat of arms.

Two flags are firmly planted in Macau and Green Island to indicate that the Portuguese were here to stay.

Parte 1 — Conquista e Conciliação — os portugueses chegam à Ásia

Uma pintura dramatizada da Batalha de Diu, 1509, que estabeleceu a supremacia naval portuguesa no Oceano Índico durante os 100 anos seguintes.

Procurando uma rota comercial para a Ásia, os marinheiros portugueses começaram a explorar a costa ocidental de África no século XV, a princípio com cautela e, depois, à medida que se foram familiarizando com as correntes oceânicas e os litorais remotos, de forma mais ousada. No final do século, dois grandes navegadores chegaram à Índia e iniciaram uma era de influência ocidental na Ásia que mudaria o mundo para sempre. Bartolomeu Dias dobrou o Cabo da Boa Esperança em 1488; uma década depois, Vasco da Gama chegou a Calecute, na costa ocidental da Índia. Nos vinte anos seguintes, uma série de cerca de quarenta fortes portugueses pontilharam a costa de África e da Ásia, enquanto Portugal, um pequeno país na fronteira com a Europa, estabeleceu durante meio século um império comercial e estratégico muito maior do que qualquer outra potência da Europa.

Foi uma conquista impressionante e deixou um legado para os cinco séculos seguintes. A ocupação portuguesa de Macau, iniciada em 1557, terminou finalmente em 1999. Macau marcou a maior extensão do império português. Foi a primeira e última colónia europeia no Extremo Oriente.

A expansão colonial é comummente o resultado de proezas comerciais, frequentemente acompanhadas de zelo religioso, sustentadas por uma força militar e naval avassaladora. Isto aplica-se amplamente às impressionantes conquistas portuguesas ao longo da costa africana e do Oceano Índico entre o final do século XV e o início do século XVI. Francisco de Almeida, que em 1506 foi nomeado primeiro vice-rei português no Oriente, e o seu sucessor, Afonso de Albuquerque, perceberam que, para garantir o comércio, deviam destruir quem se lhes atravessasse no caminho. Isto fizeram-no em 1509 na Batalha de Diu, um importante confronto naval na costa indiana. Nessa altura, a superioridade tecnológica dos portugueses na construção naval e na artilharia facilitou a vitória de Albuquerque sobre os seus adversários nos mares. Os dhows árabes não eram páreo para as caravelas e naus portuguesas, muito mais manobráveis e com melhor armamento.

No ano seguinte, 1510, Albuquerque estabeleceu uma forte base em Goa, na costa ocidental, mantida por um sultão muçulmano. Albuquerque era um estratega brilhante e, com uma força muito menor, matou 6.000 dos 9.000 defensores. Esta, com dois domínios mais pequenos, Diu e Damão, manteve-se na posse portuguesa até 1961. A conquista foi implacável, sangrenta e rápida. A superioridade religiosa e cultural portuguesa foi imediatamente afirmada. Os muçulmanos foram expulsos e a prática da religião hindu foi proibida. Goa foi vista como o trampolim para a evangelização da Índia de uma forma notavelmente militante. Começou pelo estabelecimento de numerosas casas religiosas em Goa — conventos, igrejas e seminários. No entanto, embora Goa em si tenha permanecido firmemente católica, houve pouco impacto para além das suas fronteiras. O impacto de Portugal foi, a longo prazo, demográfico e não religioso. Cerca de dois mil jovens abandonavam Portugal todos os anos em busca de fortuna na Índia; poucos regressavam. Assim, Albuquerque incentivou o casamento entre mulheres locais, dando início à longa prática de integração racial que caracterizou o domínio português, em nítido contraste com o de qualquer outro império europeu.

No ano seguinte, 1511, Albuquerque atacou Malaca, uma posição forte na costa da Malásia, defendida por uma força de 20.000 homens. Conquistando-a com uma força de 900 portugueses, 200 mercenários hindus e cerca de dezoito navios, dispôs-se imediatamente a construir um forte e fortíssimo forte, que se pretendia inexpugnável, e que foi considerado como tal durante mais de um século.

Este forte, A Famosa, foi o ponto de partida das expedições portuguesas à China e ao Japão no meio século seguinte. De frente para o mar, Albuquerque construiu uma enorme torre de menagem de pedra de quatro andares, a Torre de Menajem, a Torre de Homenagem, construída num estilo que a artilharia moderna tinha tornado obsoleto na Europa no século XVI; em Malaca, a intenção era impressionar, e não proteger. Impressionou os sultões locais, que procuraram em vão expulsar estes intrusos estrangeiros. 130 anos depois, em 1641, os holandeses demoraram quase três anos a expulsar os portugueses de Malaca após um longo e amargo cerco.

Mais a leste ficou na China. Os chineses eram conhecidos na Índia, onde as viagens do célebre almirante chinês Cheng, cerca de cinquenta anos antes, deixaram uma forte gravação. Os chineses eram vistos pelos indianos como um povo civilizado, com a pele mais clara do que a sua, e Albuquerque decidiu aventurar-se mais para leste. Ao chegar a Malaca em 1511, encontrou aí uma frota de juncos chineses. Invejo logo um dos seus capitães, Jorge Álvares, para verificar se era possível abrir comércio com aquele povo misterioso e remoto. O envolvimento português com a China estava prestes a começar, mas, desta vez, seria através de uma conciliação cuidada. Não há grandes batalhas navais, conquistas sangrentas ou cercos prolongados na longa história de Macau.

Parte 2 — Os grandes dias de Macau, 1557-1640

As primeiras tentativas portuguesas de negociar com a China no início do século XVI terminaram em desastre quando foi enviada uma embaixada à Corte Imperial em Pequim, liderada por Tomé Pires, cujo livro Suma Oriental foi uma importante obra de referência descrevendo as descobertas orientais portuguesas. Parecia ser o homem ideal para o que se revelou uma tarefa impossível. Após longos atrasos, os chineses descobriram que a comunicação ao Imperador que vinha, não do Rei de Portugal, mas do seu subordinado, o Vice-rei em Goa, não estava sob a forma de submissão abjeta considerada apropriada para os governantes bárbaros. Pires e a sua comitiva foram vistos como espiões perigosos e foram atirados para a prisão de Cantão, onde alguns foram executados em 1524, enquanto os restantes morreram miseravelmente alguns anos depois, ainda na prisão. Os portugueses descobriram, tal como outros europeus nos três séculos seguintes, que lidar com as autoridades chinesas era difícil, imprevisível e podia ser perigoso.

Este desastre interrompeu o comércio português com a China durante uma geração. Cautelosamente, outros se aventuraram a regressar. Levou algum tempo a persuadir os mandarins em Cantão de que os “bárbaros ocidentais” (portugueses) não eram uma ameaça e que fazer negócios com eles era altamente lucrativo tanto para os comerciantes como para os mandarins. Os negócios no Extremo Oriente sempre dependeram de presentes adequados, e é provável que os primeiros comerciantes portugueses a chegar na década de 1540 perto de Cantão se tenham certificado de que os seus presentes eram suficientes para satisfazer os mandarins. Abrigaram-se e negociaram em vários locais antes de encontrarem uma pequena península rochosa na foz do Rio das Pérolas com um porto abrigado. Já bem conhecido pelos chineses, este local era o local de um templo construído no final do século XV para o culto da deusa A-ma. Para os portugueses, o local passou a ser Ama-cao, eventualmente encurtado para Macau ou Macau. Em poucos anos, um pequeno povoado com alguns barracões de esteira (estruturas temporárias construídas em bambu com esteiras de vime como paredes) cresceu. Em poucos anos, este povoado tornou-se muito mais permanente, e edifícios dispendiosos e elaborados foram erguidos.

Como foi possível?

Macau e os seus mercadores beneficiaram, durante cerca de 70 anos, de uma série de circunstâncias muito favoráveis. A primeira delas foi a decisão tomada no século XIV pelos imperadores Ming, na China, de proibir o comércio com os japoneses, a quem chamavam com desprezo “os bárbaros anões”. Os japoneses, por sua vez, tornaram punível com a morte a saída do Japão. Isto significou que estes dois impérios do Extremo Oriente se desenvolveram nos três séculos seguintes por caminhos divergentes. No Japão, a prata era relativamente barata; na China, cujo sistema monetário se baseava na prata, esta tornou-se um metal cada vez mais precioso à medida que a população e a economia cresciam sob a administração estável dos imperadores Ming.

A segunda circunstância foi a descoberta acidental do Japão pelos portugueses. Em 1542, Fernão Mendes Pinto e um companheiro, que tentavam chegar à China, foram impelidos para norte por uma tempestade e chegaram ao Japão, onde os seus arcabuzes, as primeiras armas de fogo, causaram sensação. Foram imediatamente copiados pelos armeiros japoneses. Nos trinta anos seguintes, um negócio de importação e exportação incrivelmente lucrativo, conhecido como “comércio de carruagens”, foi estabelecido em Macau. Os comerciantes portugueses encontraram no Japão um mercado pronto para a seda chinesa, que atingia preços elevados, pagos em prata, a peso. O Japão produzia seda, mas os japoneses preferiam a seda chinesa, que era de melhor qualidade. A seda chinesa era comprada em Cantão por muito menos do que era vendida no Japão. Raramente na história da humanidade houve um comércio tão lucrativo, e durante mais de meio século, até ao início do século XVII, os portugueses detiveram o monopólio desta atividade.

Neste período, Macau tornou-se uma cidade próspera, com casas elegantes, adornadas com mobiliário e objectos de arte chineses e japoneses. 1 Eram habitadas por pessoas ricamente vestidas, servidas por numerosos escravos negros africanos. As pessoas vinham de Portugal para desfrutar da bonança. Segundo o Padre Manuel Teixeira, uma população de cerca de 500 em 1561 cresceu para cerca de 850 em 1635.2 Ninguém se preocupou em contar os escravos, mas uma estimativa americana feita muito mais tarde, em 1835, estimou o número então em 800-900.3 Cerca de 10.000 chineses chegaram a Macau em 1635, mas poucos ou nenhuns o considerariam como o seu local de origem (heung ha), e também ninguém se preocupou em contá-los.

Vista para oeste, com a Praia Grande em primeiro plano à esquerda.

Olhando para Este, com a Ilha Verde em primeiro plano à esquerda.

Macau por volta de 1640, uma reconstrução de Vicente Pacia.

J.M. Braga Pictures Collection, National Library of Australia.

Os viajantes que visitavam Macau no início do século XVII ficavam maravilhados com o que viam. O Padre Antônio Cardim, padre jesuíta que ali viveu de 1632 a 1636, escreveu:

Macau é composta por edifícios muito bonitos e é rica devido ao comércio e ao trânsito que ali se realizam de dia e de noite; possui cidadãos nobres e honrados. De facto, é tida em grande estima em todo o Oriente, dado que é depositária de mercadorias feitas de ouro, prata, seda, pérolas e outras jóias; de todos os tipos de drogas, especiarias e perfumes da China, Japão, Tonquim, Cochinchina, Cambodja, Macassar, Solor; e, sobretudo, por ser a sede da cristandade no Oriente.’4

Havia famílias ricas que se tornaram mecenas das artes, fervorosos apoiantes da fé e contribuintes para a vida da comunidade. Apoiaram uma irmandade de caridade, a Santa Casa de Misericórdia (a Santa Casa da Misericórdia) e instituições religiosas como conventos e orfanatos. Um conselho municipal, conhecido por Senado, foi estabelecido logo em 1585. Em breve existiam três igrejas paroquiais, São Lázaro (a mais antiga), Santo António e São Lourenço. Em 1575, foi criada uma nova diocese, com base em Macau. Inicialmente, o bispo era Bispo da China e do Japão, pois esta era uma diocese missionária. Foi construída uma bela catedral, geralmente conhecida como Sé. As principais ordens religiosas, os jesuítas, os franciscanos, os dominicanos e os agostinhos, cedo chegaram e estabeleceram missões. Cada uma tinha a sua própria igreja, dedicada ao santo correspondente, enquanto os jesuítas, primeiro no campo, construíram e, após um incêndio em 1602, reconstruíram a grande igreja que veio a ser conhecida como São Paulo. Para além destas, existiam duas igrejas anexas à Santa Casa de Misericórdia e ao Convento de Santa Clara, e uma capela anexa ao seminário jesuíta de Nossa Senhora de Amparo, onde se formavam cristãos chineses para o serviço missionário na China. Além de todas estas, existia uma pequena capela anexa ao Senado. A presença de todas estas igrejas e capelas, e o som dos seus sinos, dominavam Macau. 5

Se este grande sucesso comercial e religioso parece demasiado bom para ser verdade, era. Tudo dependia de duas coisas: o sucesso contínuo do monopólio português, extremamente lucrativo, no comércio entre a China e o Japão, e a disponibilidade das autoridades chinesas em Cantão para tolerar este lugar rico à sua porta.

Um aviso do que estava para vir foi a construção, pelos chineses, de um muro de contenção entre Macau e o território chinês, em 1573, dezasseis anos após o primeiro povoamento português permanente. Os portugueses raramente tinham permissão para atravessar a sua única porta. Nos umbrais, havia uma inscrição pontiaguda: “Tema a nossa grandeza; respeita a nossa virtude”. Os acontecimentos provariam que não se tratava de palavras vãs.

Não houve qualquer aviso em Macau sobre o estabelecimento em 1600 do negócio comercial inglês, a Honorável Companhia das Índias Orientais e a sua contraparte, a Companhia Holandesa das Índias Orientais (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie ou VOC) em 1602. Ambas teriam um impulso empreendedor sustentado e implacável que os portugueses não tinham. Pior ainda foi uma violenta reação anticristã no Japão que começou em 1614 e em 1639 levou ao martírio horrivelmente cruel de muitos milhares de cristãos japoneses e a um fim sangrento do comércio português com o Japão. Ao mesmo tempo, os holandeses estavam a levar a maior parte do comércio para oeste, e houve uma revolta violenta na China quando a dinastia Ming foi derrubada pelos manchus. Com todo o seu comércio cortado, Macau enfrentou a ruína certa.

Parte 3 — ‘Os bárbaros vermiformes de Macau’

Um século depois de o navegador português Fernão Mendes Pinto ter descoberto o Japão em 1542, o contacto português com o Japão chegou a um fim repentino. Daí em diante, o Japão seria um reino fechado durante mais de duzentos anos. Apenas 160 anos se passaram desde o fim deste longo isolamento. Por conseguinte, a duração do importante papel do Japão no mundo moderno não é tão longa como o seu período de isolamento. O que correu mal?

O primeiro meio século de contacto luso-japonês foi incrivelmente bem-sucedido. Desenvolveu-se um comércio imensamente lucrativo, para grande satisfação de ambas as partes. Os missionários jesuítas foram ao Japão juntamente com os mercadores e obtiveram o que parecia um sucesso milagroso na ilha japonesa ocidental de Kyushu, onde se situa Nagasaki. Em 1580, 150.000 pessoas tornaram-se cristãs, e o número cresceu para cerca de meio milhão em 1615. Vários daimyo, os senhores feudais que detinham imenso poder no Japão, foram convertidos.

Encorajado por este rápido sucesso, o Padre Alessandro Valignano, talvez o maior dos líderes jesuítas da geração posterior a Francisco Xavier, enviou uma prensa a Nagasaki. Foi utilizada durante cerca de vinte anos para produzir publicações devocionais e evangelísticas. No entanto, a missão foi, curiosamente, muito bem-sucedida. O mesmo se aplicava ao comércio, extremamente lucrativo para os mercadores que vinham uma vez por ano na viagem ao Japão vender seda por prata, muito mais valiosa na China do que no Japão. O monopólio de que gozavam era demasiado bom para durar e, no final do século XVI, chegaram mercadores holandeses, dispostos a tudo para expulsar os portugueses.

Para além de um comércio demasiado unilateral, o impacto do cristianismo foi visto com alarme pelo governante japonês, o xogum, a partir do seu castelo em Yedo, a cidade que é hoje Tóquio. Durante vários séculos, o Imperador em Quioto foi uma figura decorativa, enquanto o xogum, o chefe da principal família nobre do Japão, governava efetivamente o Japão. Em 1600, ocorreu um golpe sangrento, com 40.000 homens mortos na batalha pelo poder. De seguida, o clã Tokugawa assumiu o poder em Yedo. Naturalmente, o novo xogum considerava qualquer outra forma de lealdade uma ameaça à sua própria autoridade e decidiu destruí-la. Nesta forma de pensar, a ascensão do cristianismo foi sediciosa. Deve ser impiedosamente esmagada, para que não haja um regresso aos dois séculos de instabilidade que antecederam a ascensão ao poder do clã Tokugawa. O último governante do Japão antes do golpe, Hideyoshi, e depois os três primeiros xoguns Tokugawa, Ieyasu, Hidetada e Iemitsu, reprimiram a situação com crescente severidade. Hideyoshi proibiu a pregação do cristianismo e, em 1597, seis missionários estrangeiros e vinte cristãos japoneses foram punidos por desafiarem o decreto. As suas orelhas e narizes foram cortados e depois crucificados. Estes “Mártires de Nagasaki”, como ficaram conhecidos, foram os primeiros de um grande número de mortos nas quatro décadas seguintes.

“Os Mártires de Nagasaki”, de um artista desconhecido, foi limpo, restaurado e reparado em Londres com a ajuda de donativos comerciais. A pintura, possivelmente de um frade franciscano, data do século XVII e esteve anteriormente na Igreja de São Francisco (há muito demolida), mas é hoje guardada no Seminário de São José.

Entre 1614 e 1638, com a implementação de políticas progressivamente mais severas, os cristãos japoneses foram exterminados em grande número numa perseguição cruel que culminou num horrível massacre em 1638, em Shimabara. Esta fortaleza resistiu durante algum tempo às forças do Xogum e foi finalmente subjugada com a ajuda da artilharia holandesa. 37.000 rebeldes foram mortos, muitos deles atirados de um penhasco para as fontes sulfurosas e fervilhantes de Unzen. Muitos outros cristãos japoneses renunciaram à sua fé e regressaram às suas antigas práticas religiosas. Um pequeno remanescente manteve-se fiel à sua fé em segredo em aldeias próximas de Nagasaki. Os descendentes destes “cristãos ocultos” surgiram finalmente em 1865.

Até à rebelião de Shimabara, os portugueses eram tolerados pelo comércio que traziam, embora, quando um navio chegava, o seu leme e armamento fossem removidos para garantir que a sua tripulação ficava indefesa. Era uma situação impossível, e as duas últimas galiotas portuguesas abandonaram Nagasaki em 1639, tendo sido proibidas de comerciar. Em vão, os mercadores imploraram, com lágrimas a escorrer-lhes pelo rosto, que eram inocentes e que “Macau se alimenta do Japão”, e que, se formos privados deste comércio, todos recaíremos na mais extrema miséria. Imediatamente a seguir, o xogum Iemitsu adoptou uma política rigorosa de exclusão de todos os estrangeiros, excepto os holandeses, a quem era permitido enviar um navio por ano para Nagasaki, onde ficavam sob uma supervisão rigorosa e humilhante. Enquanto o governo japonês tinha sido curioso e acolhedor na década de 1540, um século mais tarde, nas mãos de uma nova família governante, tornou-se medroso e xenófobo. A 22 de junho de 1636, ainda antes da revolta de Shimabara, Iemitsu emitiu aquele que veio a ser conhecido como o Édito do País Fechado. Não poupou esforços. É bastante extenso, mas as três primeiras orações deram o mote para as outras quinze.

1.º Nenhum navio japonês pode partir para o estrangeiro.

2.º Nenhum japonês pode viajar secretamente para o estrangeiro. Se alguém tentar fazê-lo, será morto, e o navio e o proprietário serão presos.

3.º Qualquer japonês que esteja atualmente a viver no estrangeiro e tente regressar ao Japão será condenado à morte.

Esta terceira cláusula dirigia-se aos refugiados cristãos japoneses que tinham ido para Macau e que em breve construiriam a maravilhosa fachada da Igreja de São Paulo. As cláusulas posteriores estabeleciam o que deveria ser feito no caso de se descobrir algum Kirishitan (cristão), ou, pior, um Baderen (padre). O comércio limitado com os portugueses ainda era tolerado nesta fase, mas em dois anos foi encerrado. Os portugueses eram vistos como proselitistas, e o édito de exclusão foi rigorosamente aplicado.

Em Macau, o Leal Senado decidiu fazer uma última tentativa de reconciliação. Em junho de 1640, foram enviados quatro cidadãos importantes para negociar com os japoneses, acompanhados por outros cinquenta e sete. Não levaram nenhuma mercadoria. Conscientes do perigo que corriam, todos se confessaram e receberam os sacramentos da Penitência e da Comunhão antes de partirem. A dimensão da embaixada indicava claramente a importância da questão para o Leal Senado.

A viabilidade de Macau estava em causa. Uma vez em Nagasaki, os enviados foram tratados da mesma forma que qualquer cristão japonês. Em 1635, Iemitsu tinha descoberto uma forma infalível de erradicar os cristãos. Uma cruz foi levada a cada casa em Kyushu, e as pessoas foram obrigadas a cuspir nela e a espezinhá-la. Era uma escolha clara: apostasia ou martírio. Foi isso que precipitou a revolta de Shimabara. Os membros da embaixada portuguesa em 1640 tiveram a mesma escolha; nenhum cedeu, e a 3 de Agosto de 1640, todos os 61 foram decapitados e as suas cabeças expostas no mercado da cidade. Disseram-lhes que estavam a ser tratados com misericórdia. Não mereciam nada além da morte mais dolorosa, mas como não traziam qualquer mercadoria, a sentença estava a ser comutada para uma morte fácil.

O navio português foi incendiado, e os doze subordinados poupados à execução foram devolvidos a Macau com um rescrito oficial num pequeno junco chinês. O objectivo da política japonesa, explicou o seu autor, Kagazume Tadazumi, era “civilizar as pessoas e fazer com que as pessoas de países distantes o adorassem, é a virtude do Comandante Supremo”. Explicou que tudo no Japão era harmonia até que “os bárbaros vermiformes de Macau, que há muito acreditavam na doutrina do Senhor do Céu, desejaram propagar a sua religião maligna no nosso país”. Depois de relatar longamente como os cristãos japoneses tinham sido exterminados, o rescrito concluía: “Os Anciãos de Macau, ao ouvirem os factos acima, devem reconhecer a rectidão do nosso país e ficar impressionados com a força da nossa virtude militar.” 6

A notícia foi devastadora para Macau, mas a reacção imediata foi homenagear “o nobre exército de mártires”, nas palavras daquele antigo hino, cantado pelos cristãos desde o século IV d.C., o Te Deum Laudamus. Houve uma solene ação de graças na catedral, tocaram-se os sinos da igreja e houve regozijo. Parentes dos mártires vestidos, não de luto, mas com roupas de gala. A embaixada no Japão tinha falhado, mas eles acreditavam que agora tinham embaixadores no Céu, intercedendo por eles no Trono da Graça. Sem dúvida, o povo piedoso de Macau também se teria lembrado da famosa observação de Tertuliano de que “o sangue dos mártires” é a semente da Igreja. No entanto, o regozijo espiritual era uma coisa, mas as realidades temporais também tinham de ser enfrentadas. Os comerciantes expulsos em 1639 tinham razão: “todos nós recaíremos na extrema miséria”.

Carlos Montalto de Jesus, o primeiro historiador macaense a escrever em inglês, observou: “a prosperidade de Macau recebeu um golpe mortal; os macaenses, mergulhados na miséria e no desespero, viram os seus sacrifícios inúteis, a sua dignidade ultrajada, o seu comércio desaparecido”. 7 Seguiu-se um futuro muito negro e assolado pela pobreza, em que muitas pessoas morreram de fome nas quatro décadas seguintes.

Part 4 — Hard times

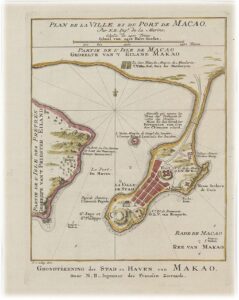

Macau em meados do século XVII.

Do acervo de Braga, Biblioteca Nacional da Austrália. nla.map-brsc108.

Durante a maior parte do seu primeiro século, desde 1550 até 1640, Macau foi próspero, mas a maior parte dos dois séculos seguintes foi um período sombrio e assolado pela pobreza. O magistrado chinês na ilha de Heungshan, da qual Macau faz parte, exercia um controlo rigoroso e apertado, e o rei de Portugal não tinha forças suficientes para fazer alguma coisa para ajudar a sua colónia mais remota.

Com o tempo, os parafusos continuaram a apertar. O magistrado de Heungshan ergueu um complexo administrativo numa posição elevada não muito longe, a fim de supervisionar Macau. Não havia como ignorá-lo; era ostensivamente pintado de branco e, por isso, era chamado pelos portugueses de Casa Branca. O seu controlo e tributação eram incontornáveis. Um dos muitos impostos era o pagamento de taxas de ancoragem para os navios portugueses no Porto Interior. Para garantir que estes eram pagos, foi construída uma Alfândega Chinesa dentro da própria cidade de Macau. Um despacho ao Imperador do Vice-Rei em Cantão afirmava que os portugueses em Macau eram “um reino com grandes e muitos fortes e uma população grande e insolente… seria apropriado impedi-los de fazer comércio em Cantão”. 8 Isto foi feito durante algum tempo, e Macau sofreu ainda mais.

Restava Goa, a importante base portuguesa na Índia. Até este laço foi quebrado quando os holandeses tomaram Malaca em 1641 e, com navios melhores, dominaram o estreito de Malaca, isolando Macau da sua terra natal. O lucrativo comércio de Manila foi também quebrado no mesmo ano, após a bem-sucedida rebelião de Portugal contra Espanha em 1640. Em pouco mais de uma década, Macau perdeu todos os seus parceiros comerciais: Japão, China, Manila e Goa. Enfrentou um desastre total. Para agravar a situação, irrompeu uma peste e, em Macau, terão morrido 7.000 pessoas, a maioria chinesas. 9 Apesar de tudo isto, os portugueses apegaram-se tenazmente a Macau, com uma resiliência e uma capacidade de sobrevivência nunca demonstradas pelas potências europeias posteriores no Extremo Oriente.

A igreja também se saiu mal. Os jesuítas portugueses em Macau viram-se em conflito, e não em cooperação, com os franciscanos espanhóis e os dominicanos de Manila na actividade missionária por todo o Extremo Oriente. Isto prejudicou os esforços de ambos e, com o colapso do comércio e da riqueza, ambas as missões entraram em declínio acentuado. O mosteiro da Ordem Dominicana chegou a ter vinte e quatro membros. Em 1670, restavam apenas três, mantidos na pobreza com grande dificuldade.

Havia apenas uma palha para agarrar: a supremacia da Coroa Portuguesa. Ofuscados pelos espanhóis na vizinha Manila, os portugueses em Macau agarraram-se obstinadamente à sua identidade separada depois de Portugal ter estado sob domínio espanhol de 1580 a 1640. Durante este tempo, os reis espanhóis deixaram o remoto e obstinado posto avançado português em grande parte à sua sorte. Na restauração do trono português em 1640, o Senado de Macau conseguiu enviar ao novo rei, João IV, um presente de duzentos canhões de bronze, fundidos localmente. O rei João, informado da tenacidade deste pequeno lugar no extremo mais remoto da terra, terá dito espantado: não há outra mais leal – ‘não há outro mais leal’. Pouco antes da sua morte, em 1654, foi acrescentado ao lema da cidade, e o Conselho de Macau ostentou orgulhosamente o título de Leal Senado até 1999. Foi um gesto que na realidade pouco significou, porque Macau era pobre, com uma população em declínio e restava pouco para além de um passado magnífico no qual se basear.

A deterioração foi generalizada. Braz de Castro, nomeado governador e capitão-general em 1648, recusou a nomeação alegando que o anterior governador tinha sido assassinado. 10 Um frade dominicano espanhol visitante, Domingo Navarrete, escreveu em 1672 que “seria necessário muito tempo e papel para escrever apenas um pequeno resumo das confusões, tumultos, disputas e extravagâncias que ocorreram em Macau”. 11 Esta era a sociologia da pobreza enraizada em acção. Desenvolveu-se um padrão de falta de discernimento, de paroquialismo, de quezílias incessantes e de incapacidade de aproveitar oportunidades que se tornaram demasiado profundas para serem quebradas.

O pior ano foi 1662, quando uma revolta na província de Guangdong (Kwangtung) levou a uma ordem imperial para evacuar a costa. A população chinesa de Macau fugiu em massa, tendo a fronteira sido encerrada durante três meses. Muitas pessoas morreram de fome, mas Macau sobreviveu por um triz, porque convinha aos mandarins permitir que permanecesse enquanto fossem devidamente subornados.

Navarrete descreveu com desgosto uma delegação do Leal Senado à Casa Branca:

Vão em grupo, de varas nas mãos, até ao Mandarim, que reside a uma légua dali, e ajoelham-no para suplicar. O Mandarim, na sua Resposta, escreve o seguinte: “Este povo bárbaro e brutal deseja tal e tal coisa: que seja concedida.” Ou “recusou-as”. Assim, regressam em grande estilo à sua Cidade, e os seus Fidalgos, ou Nobres, com o Distintivo da Cavalaria da Ordem de Cristo pendurado ao peito, partiram para estas missões… se o seu Rei soubesse destas coisas, é quase inacreditável que as permitisse.”

Tal foi de facto proibido pelo Rei D. João V em 1712, mas em Macau, longe da corte real, nada mudou. Estas pessoas empobrecidas e desmoralizadas estavam isoladas da sua pátria distante e da autoridade real. O mandarim governava aqui. Por necessidade cruel, os conselheiros desenvolveram uma prática de subserviência servil às autoridades chinesas na Casa Branca e na alfândega chinesa dentro dos seus próprios muros. Tinham que fazer isso para sobreviver. A visão espanhola de Navarrete, hostil aos portugueses, era a de que o povo de Manila era livre, mas que o povo de Macau era escravo dos chineses. Estavam de facto presos numa situação nada invejável, atormentados pela penúria e sem saída. Mesmo que se pudessem encontrar navios para os levar, para onde iriam e como escapariam ao controlo holandês do Estreito de Malaca?

No entanto, durante todo este período de cerca de dois séculos, apesar das severas restrições que suportou durante tanto tempo, a comunidade portuguesa de Macau continuou a demonstrar um grau surpreendente de resistência obstinada. São qualidades que perduram até aos dias de hoje, pois somos herdeiros da sua persistência.

Parte 5 — Luta pela sobrevivência

As coisas melhoraram, mas muito lentamente. A melhoria poderia ter sido muito maior, não fossem algumas decisões erradas. No final do século XVII, a influência jesuíta cresceu na corte do Imperador em Pequim, principalmente através do destacado astrónomo jesuíta, o Padre Verbiest, que granjeou a confiança do Imperador Kangxi a tal ponto que, em 1685, decretou a abertura dos portos chineses à navegação estrangeira. Esta deveria ter sido uma oportunidade de ouro para Macau recuperar grande parte do seu antigo estatuto, mas a oportunidade de o assumir escapou por entre os dedos do Senado de Macau, que viu o decreto imperial com ressentimento e desconfiança. Viam-no como algo que os privava dos direitos monopolistas de comércio com Cantão que Macau tinha sob a dinastia Ming antes da sua queda na década de 1640.

O imperador subestimou a importância que o comércio externo viria a ter, mas começou de forma modesta. Era necessário algum controlo, pelo que, em 1719, o imperador Kangxi, no final do seu reinado, propôs novamente centralizar todo o comércio externo da China em Macau. Por incrível que pareça, a oferta imperial foi mais uma vez rejeitada, vista como um “cavalo de Tróia”, dando aos chineses uma presença e um controlo muito maiores em Macau do que já tinham. O Senado hesitou perante o custo de ter de disponibilizar cinquenta a sessenta funcionários para gerir a proposta. Talvez a rejeição não tenha sido tão tacanha como poderia parecer. O Senado já tinha assistido a muitos casos de mandarins locais a extrair todo o dinheiro possível de quaisquer operações lucrativas empreendidas pelos portugueses. No entanto, gradualmente, mudaram de ideias, mas já era tarde demais. Em 1732, treze anos depois, o imperador Yongzheng renovou a proposta. Desta vez, o Senado estava entusiasmado.

No entanto, o Bispo de Macau não o fez, pois isso traria comerciantes ingleses, hereges protestantes, para a Cidade do Nome de Deus. Embora os estrangeiros não tivessem permissão para residir em Macau, vários infiltraram-se como “inquilinos”. A maioria era constituída por solteiros, e o efeito na vida nocturna de Macau era previsível; estes homens não eram monges. Temendo pela moral do seu rebanho, o bispo persuadiu o Vice-Rei da Índia, Pedro Mascarenhas, a ignorar a vontade do Senado. Em vão, o Senado protestou.

Pela terceira vez, a hipótese de recuperação económica de Macau foi posta de lado, desta vez pela autoridade suprema do Vice-Rei em Goa. Entretanto, os mercadores britânicos demonstravam um crescente interesse no comércio com a China. Negociavam sobretudo com chá, curiosidades orientais e porcelana, que ficou conhecida na Grã-Bretanha como “porcelana”. O ópio chegou depois. Os seus navios eram maiores e já era claro que as águas pouco profundas em redor de Macau eram perigosas para a navegação. Após a proibição do vice-rei, os britânicos foram até à ilha vizinha de Lintin, no estuário do Rio das Pérolas, para negociar com os comerciantes chineses, em vez de atracar em Macau.

Auguste Borget, “Macau visto dos Fortes de Heang Shan”, 1839.

Olhando para sul, o Forte da Guia está no cimo da colina à esquerda, e o Forte do Monte à direita, com a cidade no meio, atrás de uma muralha protetora. Em primeiro plano, uma cerimónia fúnebre chinesa.

Em meados do século XVIII, o crescimento constante do comércio externo levou a China a reconsiderar as bases sobre as quais este era conduzido. Só em Cantão a máquina administrativa estava suficientemente bem desenvolvida para regular o comércio e os comerciantes de ambos os lados. Em 1760, todos os portos foram novamente encerrados, exceto Cantão, e foi emitido um conjunto de oito regulamentos para regular o comércio. Como de costume, as proibições neles contidas eram negociáveis pelo método tradicional de “aperto”. No entanto, num caso, não havia espaço para concessões. As mulheres estrangeiras não eram permitidas em Cantão, e os estrangeiros eram autorizados a residir lá apenas durante a época de comércio, confinados a uma pequena área fora da cidade amuralhada. O motivo era óbvio. Os chineses sabiam que a residência permanente de estrangeiros de ambos os sexos criaria uma outra colónia europeia.

Isto criou um problema imediato para o vizinho Macau, que há pouco tempo proibia a residência de estrangeiros, ou seja, protestantes. Se Macau continuasse a excluir os residentes estrangeiros, era provável que forçassem a entrada. Neste caso, os chineses dificilmente os impediriam, pois era conveniente tê-los por perto, mas não dentro do acampamento. Para o Senado, uma solução pragmática era vital para que Macau não perdesse todo o seu comércio. Assim, a proibição foi levantada, apesar das objecções do bispo; estrangeiros podiam viver em Macau, mas não lhes era permitido possuir propriedades.

O Senado tinha razão ao assumir que esta medida era essencial para a sobrevivência de Macau. Muitos anos mais tarde, um oficial do exército inglês observou: “Os mercadores ingleses apenas alugam casas aqui, mas desde que foram forçados a retirar de Cantão e a residir neste lugar, Macau passou de uma condição quase arruinada para uma condição muito próspera. Tanto os portugueses como os chineses prosperam com a riqueza e a indústria britânicas.” A pobreza que oprimia os macaenses durante gerações começou a diminuir, sobretudo graças ao vigoroso empreendedorismo dos recém-chegados, sobretudo da Companhia das Índias Orientais. Esta enorme empresa mercantil foi a primeira corporação multinacional do mundo. Os seus negócios foram efetivamente globalizados três séculos antes do termo existir.