Experiences at Shamshuipo & Sendai Camps

Shamshuipo Camp

[After Hong Kong’s surrender on December 25, 1941,] it took us twelve hours to reach Shamsuipo Prisoner-of-War Camp as there were over 10,000 men and only two ferries, so we had to walk all the way from Star Ferry, a distance of about two miles, lugging all our belongings.

We were put in Quonset huts with about 50 men in each hut. No. 6 Company personnel had their own hut, and No. 5 Company and Field Ambulance of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force were next to us. In fact, the Volunteers were all in a row as we were under the command of the same sergeant major.

Besides the Volunteers, there were the Royal Scots and Middlesex Regiments, one Indian artillery regiment, one Chinese Field Ambulance Section, and the two Canadian Regiments – the Royal Rifles of Canada, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers. After the Chinese and Indians were later released, there was a rumour that we (the Portuguese) would also be released, but this never happened.

It was winter and very cold, and the windows and the doors of the huts had all been looted so we had to go scrounging (a polite word for stealing) for pieces of wood and corrugated metal sheets to fabricate our own with the help of the Royal Engineers.

POWs allowed to send only one letter a month

We were allowed to write one letter a month which was only sent out after being censored by the Japanese. What you could say: “Dear Mom, How are you? I’m well. Your loving son.”

Father Green tended to our spiritual needs, saying mass every morning in one of the huts. Leonel Silva was his aide. (Leonel’s father, Nado, was also in the camp). The Engineers built us a brick altar to give us quite a chapel. Father Green was badly beaten up by the Japanese one day, but I never found out why. [In his memoirs published here in Spring 1998 Luigi Ribeiro, who was also a PoW, wrote:

“Fr. Green had reason to believe that the camp authorities had not spent all the money received from the Vatican. He had the brazen audacity of going to the Japanese to ask for an explanation in connection with the disbursement of the Vatican funds.

For his impudence, Fr. Green was given such a battering that he passed out completely and had to be revived by throwing water over his face.” – Ed.]

We had a hospital and a mortuary, both of which had no proper windows or doors, so when we walked by these places we could watch the doctors and staff going about their business.

We also had a chicken farm, a pig farm and a football field, a garden full of tomatoes, melons and lots of greens, but they were only for hospital patients so there was no chance of scrounging, as there were guards all over the place – Japanese, and our own men.

The pigs in the farm were huge, like cows, which the Engineers killed by hitting them over the head with a wooden mallet. We once sat on the side of the field and watched this pig chase the Engineers. More Engineers had to come out to help them.

POWs forced labour at Kai Tak, Aberdeen and Lai Chi-kok

We were put to work in Kai Tak Airflield, cleaning nullahs (large, open boxed culverts) and shovelling down a whole hill (quite a mountain) to enlarge the airport. A few soldiers died because of landslides, despite our futile efforts to dig them out.

We had a first-aid station under a tree and the sick could go there to rest and recuperate. On the first day, there were two or three of us. The next day, there were ten. Then everybody got into the act until the Japanese sentries chased us away with fixed bayonets. Then it was back to normal, with two or three genuine patients, for the others preferred not to get “sick”. Anyway, at Kai Tak, the grass was so long that you could go to sleep and the guards couldn’t see you.

We also had to shift bombs from one godown to the other stacking and unstacking the 500 and 1,000 pound bombs.

The other big job was at Aberdeen. We had to take oil and kerosene drums down to the pier and then later load them on to a barge to be taken to Lai Chi-kok Socony (Standard Oil Company of New York) Installation. There were so many drums that it took us six months to clear the godowns.

We got up at 5:00 a.m., had breakfast, and waited on the parade ground to be counted. Then we were put on a barge which took over an hour to reach Aberdeen. Most of us slept on the barge and others chatted and read books. The Japanese brought in a lot of books giving us quite a good library. (The books were looted from private libraries in the Colony – Ed.)

Allies bomb targets in Hong Kong

While we were working on the drums, an Allied spotter plane flew over us every morning. The air-raid siren went and the Japanese guards ran up the hills, far away from the drums. We sat on the drums, and as we had our own spies, we knew the same spotter plane came over every morning. The American bombers never bombed the prison camp as if they knew where we worked.

When all the drums were taken to Lai Chi-Kok, the spotter plane still came around as usual, and the siren went and everyone looked towards Lai Chi-Kok. On September 2, 1942, a heavy droning sound led us to believe that this was it. The huge tanks went up in a black mushroom cloud, and we could see the drums going up through the smoke followed by many fighter planes strafing the godowns until there was nothing left.

The fire in Lai Chi-Kok burned for a week. Every day, we took our bowl of rice at dinner time to the field and watched the huge fire, singing, “Over there, everywhere, the Yanks are coming”. By the third day, the Japanese guards were also singing with us. If they found out what we were singing they would have set on us with bayonets.

Health problems

Some men did die of dysentery. When my uncle had it, he weighed only 40 lbs. I could have carried him on his stretcher by myself. The Japanese sent him to Queen Mary Hospital, and after three months, he returned. When I saw him, I said, “Uncle, I thought you were dead.” He chased me around the room.

In a primitive operating theatre, British Army doctors fought to save lives. Their instruments were razor blades and knifes; the drugs, salt and peanut oil. Even those were precious and zealously guarded. The Japanese had taken over enormous stores of medical supplies which they used only for their soldiery. Later, by bribing sentries, essential drugs were secured in minute quantities.To obtain money for this, men sold to the sentries, all they had including gold teeth.

When there was an infestation of bugs, flies and rats during the dysentery outbreak, the Japanese offered a packet of cigarettes for every 100 flies caught. Some of the prisoners went around with their drinking mugs to catch flies. If they caught a big fly they would break it in two; that way, they would earn their pack of cigarettes anyway as the Japanese didn’t bother to count the pests.

Being afflicted with scabies was like having boils all over one’s body. The treatment was having the patient hold on to a bar in front of him while the medic helper scrubbed his back with a brush with long bristles. This treatment would cause his back to bleed, and was so painful that he would faint after the second pass. This treatment would go on until the patient was cured, but that was impossible given the poor food we were getting.

When cases of diphtheria occurred soldiers were dying like flies because there was no serum for its treatment. Those who went into hospital, would die on the third day. Each time someone died, the bugler would blow his horn, but after ten men died in one day, the Japanese stopped this practice.

In the hospital, the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) tended to the sick and dying, but tended towards the dying for they were suspected of grabbing a patient’s belongings when he eventually called it quits. The kwai-lohs cynically told us that RAMC also meant “Rob All My Comrades”.

We had a Canadian dentist who was very thin and weak from malnutrition. When I had a toothache and couldn’t eat I joined in the queue to see him. I told him, “I’m going to scream, but don’t mind me, and keep pulling.” He did just that, but he was so weak he literally had a foot on my chest, believe it or not, as he tugged. I screamed louder when he broke my tooth into three pieces, and then he had to do this all over again two more times.

After a month or so, I had another bad tooth. This time, he got me out of the queue and said, “You first.” He tugged and once again I screamed, only the screaming was no acting as my tooth was being pulled without any painkillers – we didn’t have any.

After all that screaming, the guys in the queue ran away. That’s why I was always first whenever the dentist saw me. I had six more teeth extracted in the camp, and shuddered each time. I was a brave man then. Not anymore. After the war I had all my teeth pulled out (with injections of anaesthetic course). Now I have two sets of pearly white teeth and no more toothache. When I was sent to Japan, a friend told me that the dentist had died in camp.

Everything was tasteless. As it was, most of the time we just had half a mess tin of rice, and a bowl of hot water, twice a day. Sometimes we had vegetables. The same stuff for six months – chrysanthemum leaves, chili water, etc. The English engineers threw out the pei-tan (preserved black eggs) because they looked “rotten”.

Fights

Most of the guys in the camp were already hot-tempered, and as we were given chili water many fights occurred among us. I remember one fight where one of our boys was beating up this other guy, and he turned to us and said in Macanese, “Stop the fight. I’m out of breath.” We stopped the fight and called it a draw to save face for the kwai-loh.

One of the prisoners was a bully who kept picking on small and sickly people. One time, he picked on a tall American seaman who also happened to be a boxer. They sparred until the American hit the bully on the mouth knocking out his false teeth, stopping the fight. Everyone helped look for his teeth, and when these were found, the fight continued. But eventually we had to stop it as it was too one-sided. After that the bully was very careful who he picked on.

Escapes

With outside help there were a few escapes from the camp. Whenever there was an escape the whole camp had to parade on the football field as punishment for as long as twelve hours, and sometimes in the rain. We would have to miss a meal. Eventually barbed wire was placed in the nullahs (open drainage channels) to deter escapes. The Japanese also made us sign a paper saying we would not escape.

The Japanese would search the huts and confiscate a cart full of electric wires, and stamp flat all our frying pans. You had to pay three cigarettes for another frying pan. These were made by the engineers by welding a handle to a sweet (candy) or biscuit tin. The engineers also made clogs when your shoes wore out. They made a lot of cigarettes as the shoe straps would get old, and would snap when wet. You felt like a woman walking around with a shoe with a broken high heel.

Whenever something the Japanese considered negative happened in camp, such as an escape or a prohibited radio found, visitors from outside would know because the POWs had to squat and wait for hours until the Japanese would come, and tell them “No parcels today.”

After some prisoners had escaped, the barbed wire fence around the camp was electrified, and turned on at night. In the morning, the guards would switch off the electricity. One morning they forgot. A prisoner who was sweeping the ground near the fence, accidentally touched it and was electrocuted. The people working with him, seeing what had happened, ran to the guard house to tell the guards to switch off the current, but when they returned, the poor blighter was already dead. I forget his name, although he was a good friend. I think he worked with Alex Azedo in Optorg & Co.

In camp, we learned to make our own beds. There was Japanese inspection every morning. We cooked a lot of stuff but mostly with oil and soy sauce in our chow-fan (fried rice). We hammered nails to hold our clog straps, and we darned socks, and sewed on buttons. The smart woman will marry an ex-prisoner-of-war. (With servants, my wife had nothing to do; so she learned to play mahjong, and now she is fully occupied).

Whenever we washed our clothes, we hung them on the wire, got a chair and a good book, and waited until they dried. If not, someone might come knocking, trying to sell you your own pair of pants or shirt that you had just washed! If your clothes were too old for them to steal to sell, the advice was to wait for rain and hang them on the line. Later the sun would come out and dry them.

The latrine was about half a mile away from the huts and we complained to the authorities about the long walk at night and especially in the winter. For once, the Japanese understood, and allowed us to each have a tin. We would pass water, put the tin under our tatami, and then take them to the latrine in the morning. Like hell we did. We emptied them out the window.

One night, one of the POWs filled his tin and threw it out of his neighbour’s window. But the window was closed and the urine splashed over this neighbour. The perpetrator pretended to be asleep when he heard his neighbour mutter, “My, it’s raining. Funny, the windows are closed – the ceiling must be leaking.” The neighbour put a bucket next to his head and went back to sleep.

The Japanese brought in a lot of sports equipment for the prisoners to use in their spare time. We played baseball, soccer, hockey, tennis, volleyball and even lawn-bowls, but the bowls didn’t last very long as we were playing on sand. The little grass was reserved for smokers who weren’t to know until two decades later that they were also smoking grass. We were just prisoners. Some of the boys also learned bridge and chess.

One day, the Japanese challenged us to play baseball. We fielded a good team. When a certain Japanese came up to bat, a lot of voices shouted, “Come on, get this guy.” He put down the bat and asked, “Who said that?” Nobody answered. But we struck him out.

This guy’s nickname was “Slap-Happy”. A Japanese-Canadian, he who went about slapping people for no reason at all. He was hanged after the war, and was very arrogant at the trial, but he was no match for Marcus da Silva who was the prosecutor.

In those days almost everyone smoked. “No Smoking” signs were rare. Cigarettes such as Camels, Lucky Strikes, Capstan, etc., were popular. But as the war progressed these imported smokes were increasingly rare in camp and were prized. Cigarettes were bartered for other desired commodities. In fact we smoked any cigarette – pine needles, tea leaves, grass – you name it.

We also had Japanese cigarettes which were very strong. One puff got you dizzy. We called them “killers” and “cow dung”. In offering someone one of these Japanese cigarettes, we would say, “Here have a cow dung.”

One of the kwai-lohs in the camp would often come up to you when you were smoking and say, “Give us a light, chum.” Then you’d see your cigarette getting shorter and shorter. This guy had a hollow piece of paper and was smoking your cigarette. We got mad but also wise to this trick.

Nanelli Baptista, an artist and chain-smoker at Christmas, would make a greeting card for three cigarettes. (I traded a pair of knitted gloves for five cigarettes). Naneli had so many orders that I had to help him, and almost became a chain-smoker myself.

Every Christmas, we wished each other and hoped to see everyone outside by the following Christmas. As two more Christmases in camp went, our hopes waned.

Trading outside the camp fence

Despite the grimness of camp life, there were lighter moments. We used to buy some provisions from outside. In the beginning, we were buying Chinese cakes for a dollar, but later the cakes shrank from a five inch diameter to one inch so that they could fit through the fence when only a few guards were around. You would take the cake in a “one-two-three” grab as the seller outside would take the money simultaneously.

Once a PoW tore a dollar bill in half and bought a bag of sugar this way. The prisoner had the sugar and the Chinese outside the fence got cheated with half a dollar. The PoW had a good laugh. The next day he went hunting again with the other half of his dollar. But this time the Chinese seller with the sugar was disguised, and when “one-two-three” was called, they grabbed simultaneously. The seller now had the other half of his dollar, but the PoW got his comeuppance with only a packet of sand!

One day my Mom sent me a papaya and since the following day was Sunday I saved it for a Sunday treat with a few friends. Fearing foraging rats, I tied the ends of the papaya with a long string to nails on both sides of the room, dangling it in the middle of the room. How could I have guessed that this little (or big) rat was a wire-walker. In the morning, I found a neat hole bitten through the papaya. No matter. I cut around the hole and shared the dessert with others.

In our hut, for a while, there was this chomp-chomp sound on the roof every night. It didn’t bother us, but this particular mama’s boy complained to the padre that he thought the hut was haunted, so the padre brought in some holy water, and blessed the hut. But the chomp-chomp continued. One night, there was the usual noise, and bingo, a huge rat fell out from a hole in the ceiling, but it ran out of the hut, too fast for us to catch it.

The married and older POWs constantly worried about their wives and children on the outside. We, the younger people between 20 years and 30 years old, did our best to help these married people, joking and telling them funny stories. Thank heavens they listened and joined in.

Morale boosters

Morale of the man in camp was boosted by music and stage shows produced by the camp inmates. The late Johnny Fonseca who was very popular in camp, and well known even to the English and Canadian POWs, did a lot for our boys with his guitar. He accompanied us while we sang with some kwai-lohs joining in.

We also had concerts for which full credit must be given to Nanelli Baptista, his helpers and the Royal Engineers crew for the stage setting, to Eli Alves, Reinaldo Gutierrez and [Mario Francisco] Alarcon for their very sweet violin music; to the “girls” – Sonny Castro (who dressed as Carmen Miranda), Eddie and Gussy Noronha, Robert Pereira and a few more. (You couldn’t say they were not girls unless you disrobed them!)

The Japanese camp commandant, his entourage, and some outside friends usually came to these events, occupying the first three rows in the improvised theatre, arriving in limousines, while we looked at them the way movie fans ogle the stars when they arrive for the Oscar awards in Hollywood.

Before I say something about George Ainslie [Private 2841], a good friend who at 18 or 19 was our youngest PoW at Shamshuipo, I must digress: he and I (and others) used to dive together at the old Victoria Recreation Club (V.R.C.) on the Hong Kong waterfront. At first, we were diving from the lower one-metre board, then the three-metre board, and then from the verandah into the pool. We couldn’t go any higher so we dove from the window in the clubhouse into the sea. Finally, we ended up on the roof of the building, and looked down. All we could say was, “Jeepers”, so we climbed down, but one of the guys slipped and fell into the sea. It was then that we saw the huge crowd on the waterfront having a free show. But the show must go on.

The height was scary; about seven storeys high, and to add to the danger, the water below was relatively shallow, being at low tide. Our hearts must have stopped as we took the plunge which, seemingly took a long time to reach the water. But all of us: Eddie (Monkey) Roza, Lionel Roza-Pereira, Peter Rull, Manaelly Roza, Hugo Ribeiro and a guy called Pullen [William P, Gunner DR284], took the plunge. I had a stiff neck for a week. Now back to Shamshuipo camp.

George Ainslie died of diphtheria in the prison camp and Pullen died in the war. David Hutchinson [Private 3552] was the fellow with the scabies, and fainted when they scrubbed his back. He was very friendly with our boys as he was a member of the VRC and the Colony’s 100-yard swimming champion. (After the war, he went to Australia, married an Australian Catholic girl, became a Catholic himself, and went to mass every day. I’m quite sure a lot of us don’t go to mass every day – not yours truly anyway – but if you say there is a mahjong game at 6.00 a.m. I bet a lot of us will get up at 5.00 a.m.).

Drafted to go to Japan

One fine day (in August, 1944) we went out on a working party, and on returning (to Shamshuipo) at 6:00 PM., the Japanese camp commandant and a few dignitaries were waiting for us at the football field. They were there to pick the fitter men to go to Japan. They made us walk around the field, couldn’t make up their minds, and finally said, “All go.”

We were put on one side of the camp, separated from the other prisoners by barbed wire. We made a hole in the barbed stuff and came out to chat with our friends and returned at night to sleep. One chap almost got caught by the Japanese sentry. He ran and jumped over the fence. The guard fired but missed. This was Zinho Gosano.

The Japanese doctors and specialists were there every day to give us injections, swabs and other tests. I think there were about 20 in all. You would have to stand in line whether your turn was today or tomorrow. One chap objected to having a small glass rod inserted in his back-side to extract a stool sample by passing gas at the critical moment. The medic got the full blast, and showed this chap that he was really mad. It’s a wonder he survived the beating.

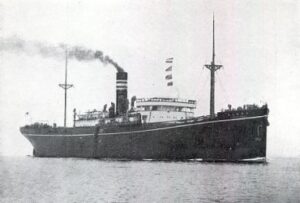

An earlier ship that left our camp with soldiers for Japan in September 27 1942, mostly men from the Royal Scots and Middlesex Regiments, were on the Lisbon Maru which was sunk by an American submarine, the U.S.S. Grouper, with the loss of some 1,000 Allied POWs. Most were machine-gunned by the Japanese when, trapped in the hold of the sinking ship, the prisoners attempted to come up on deck to save themselves. [For the definitive source, see: “The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain’s Forgotten Wartime Tragedy” by Tony Banham, Hong Kong University Press, 2006 – Ed]

We were going to see another country and we were not unhappy as we had only traveled only as far as Macau previously. Danger at this juncture never crossed our minds.

We were the second lot to get shipped out. [The latest research shows that it was the fourth of five contingents of POWs sent to Japan as slave laborers – Ed] The first lot was sent to the docks in Toyama, Japan, earlier in the year.

The list, below, of Macanese men in the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps who were sent to the coal mines in Japan: [We’ve updated the author’s list with information from a website maintained by the “Center for Research, Allied POWS Under the Japanese for the Detailed Study of Guam and all Allied POWS used as Slaves by the Japanese in World War II” and other sites – Ed.]

Experiências nos Campos de Shamshuipo e Sendai

Publicado anteriormente em Voz de Macaenses de Vancouver e em outras fontes; selecionado das memórias de Cicero Rozario e A. V. Skvorzov, sobre a Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps.

Campo de Shamshuipo

[Após a rendição de Hong Kong, a 25 de dezembro de 1941,] demorou cerca de duas semanas para reúnir todos os prisioneiros. Fomos transferidos para o Campo de Shamshuipo, caminhando quase três quilómetros a carregar os nossos pertences. Ficámos alojados em barracões do tipo Quonset.

[Após a rendição de Hong Kong, a 25 de dezembro de 1941,]

Era inverno e fazia muito frio; as janelas e portas estavam partidas. Não havia cobertores suficientes. Com a ajuda dos Royal Engineers, improvisámos alguns a partir de sacos e folhas.

Prisioneiros podiam enviar apenas uma carta por mês

Permitiam‑nos escrever uma carta por mês, em impresso próprio, de poucas linhas. O capelão católico, Padre Rigby, celebrava missa todas as manhãs num dos barracões; Leonel Silva era o seu ajudante.

Trabalho forçado dos prisioneiros em Kai Tak, Aberdeen e Lai Chi‑Kok

Fomos destacados para trabalhar em Kai Tak, limpando nullahs (valas) e removendo tambores de combustível que os japoneses tinham enterrado. Cavávamos até encontrá‑los e depois desenterrávamo‑los. Tínhamos um posto de primeiros socorros debaixo de uma árvore, junto à margem.

Aliados bombardeiam alvos em Hong Kong

Enquanto trabalhávamos, um avião de reconhecimento aliado sobrevoou e anotou os depósitos. Dias depois, bombardeiros americanos atacaram; parecia que o mesmo avião de reconhecimento passava todas as manhãs.

Os americanos também bombardearam Kai Tak e navios na baía. Fomos então enviados para Lai Chi‑Kok para limpeza; parecia terra de ninguém, sem árvores, com crateras por todo o lado.

Problemas de saúde

Alguns homens morreram de disenteria. Quando o meu tio adoeceu, emagreceu tanto que o reconheci apenas pela voz. Voltei a vê‑lo tempos depois e brinquei: “Tio, pensei que tinhas morrido.” Ele correu atrás de mim pelo barracão.

Quando houve uma infestação de insetos, moscas e ratos durante o surto de disenteria, os japoneses ofereceram um maço de cigarros por cada 100 moscas capturadas. Alguns prisioneiros andavam com as suas canecas para capturar moscas. Se apanhavam uma mosca grande, partiam-na em duas; assim, ganhavam o maço de cigarros de qualquer maneira, uma vez que os japoneses não se preocupavam em contar as pragas.

Ter sarna era como ter furúnculos por todo o corpo. O tratamento consistia em fazer com que o paciente segurasse uma barra à sua frente enquanto o auxiliar médico lhe esfregava as costas com uma escova de cerdas longas. Este tratamento fazia-lhe sangrar as costas e era tão doloroso que desmaiava após a segunda passagem. Este tratamento continuava até o doente estar curado, mas isso era impossível devido à má alimentação que recebíamos.

Quando ocorriam casos de difteria, os soldados morriam como moscas porque não havia soro para o tratamento. Os que eram internados no hospital morriam ao terceiro dia. Cada vez que alguém morria, o corneteiro tocava a sua trombeta, mas depois de dez homens morrerem num dia, os japoneses pararam com esta prática.

Quando houve uma infestação de insetos, moscas e ratos durante o surto de disenteria, os japoneses ofereceram um maço de cigarros por cada 100 moscas capturadas. Alguns prisioneiros andavam com as suas canecas para capturar moscas. Se apanhavam uma mosca grande, partiam-na em duas; assim, ganhavam o maço de cigarros de qualquer maneira, uma vez que os japoneses não se preocupavam em contar as pragas.

No hospital, o Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) assistia os doentes e moribundos, mas cuidava dos moribundos, pois eram suspeitos de roubar os pertences de um paciente quando este finalmente desistia. Os kwai-lohs disseram-nos cinicamente que RAMC também significava “Rouba Todos os Meus Camaradas”.

Tínhamos um dentista canadiano que estava muito magro e fraco devido à desnutrição. Quando tinha dores de dentes e não conseguia comer, entrei na fila para o ver. Eu disse-lhe: “Vou gritar, mas não se incomode comigo, e continue a puxar”. Ele fez exatamente isso, mas estava tão fraco que literalmente colocou um pé no meu peito, acreditem ou não, enquanto puxava. Gritei mais alto quando ele me partiu o dente em três pedaços, e depois teve de fazer tudo de novo mais duas vezes.

Passado mais ou menos um mês, tinha outro dente mau. Desta vez, tirou-me da fila e disse: “Tu primeiro”. Puxou e mais uma vez gritei, só que os gritos não eram fingimento, pois o meu dente estava a ser extraído sem analgésicos – não tínhamos nenhum.

Depois de toda aquela gritaria, os tipos da fila saíram a correr. É por isso que eu era sempre o primeiro quando o dentista me via. Extraí mais seis dentes no campo e tremia de cada vez. Eu era um homem corajoso naquela altura. Já não sou. Depois da guerra, todos os meus dentes foram arrancados (com injecções de anestesia). Agora tenho dois conjuntos de dentes brancos como pérolas e sem mais dores de dentes. Quando fui enviado para o Japão, um amigo disse-me que o dentista tinha morrido no campo.

Tudo era sem sabor. Na verdade, na maioria das vezes, comíamos apenas meia lata de arroz e uma tigela de água quente, duas vezes por dia. Às vezes comíamos legumes. A mesma coisa durante seis meses – folhas de crisântemo, água com pimenta, etc. Os engenheiros ingleses deitaram fora os pei-tan (ovos pretos em conserva) porque pareciam “podres”.

Brigas

A maioria dos rapazes do acampamento já estava irritada, e enquanto nos serviam água com pimenta, muitas brigas aconteceram entre nós. Lembro-me de uma briga em que um dos nossos rapazes estava a abanar um outro rapaz, e ele virou-se para nós e disse em macaense: “Parem a briga. Estou sem fôlego.” Interrompemos a luta e declaramos empate para salvar a cara do kwai-loh.

Um dos prisioneiros era um rufia que estava sempre a implicar com pessoas pequenas e doentes. Certa vez, implicava com um marinheiro americano alto que, por acaso, também era pugilista. Lutaram até que o americano atingiu o rufia na boca, partindo-lhe a dentadura, interrompendo a luta. Todos ajudaram a procurar os seus dentes e, quando estes foram encontrados, a luta continuou. Mas, eventualmente, tivemos de a interromper, pois era muito unilateral. Depois disso, o rufia passou a ter muito cuidado com quem implicava.

Fugas

Com ajuda externa, houve algumas fugas do campo. Sempre que havia uma fuga, todo o campo tinha de desfilar no campo de futebol como castigo até doze horas, e por vezes à chuva. Tínhamos de perder uma refeição. Eventualmente, foi colocado arame farpado nos nullahs (canais de drenagem abertos) para impedir fugas. Os japoneses também nos fizeram assinar um documento a dizer que não iríamos escapar.

Os japoneses revistavam as cabanas, confiscavam uma carroça cheia de fios elétricos e espezinhavam todas as nossas frigideiras. Era necessário pagar três cigarros por outra frigideira. Estas eram feitas pelos engenheiros soldando uma pega a uma lata de rebuçados ou bolachas. Os engenheiros também faziam tamancos quando os sapatos se desgastavam. Faziam muitos cigarros, pois as tiras dos sapatos envelheciam e rebentavam quando molhadas. Sentia-se como uma mulher a andar por aí com um sapato com o salto alto partido.

Sempre que algo que os japoneses consideravam negativo acontecia no campo, como uma fuga ou a descoberta de um rádio proibido, os visitantes de fora ficavam a saber, pois os prisioneiros de guerra tinham de se agachar e esperar horas até que os japoneses chegassem e dissessem: “Não há encomendas hoje”.

Após a fuga de alguns prisioneiros, a vedação de arame farpado em redor do campo era eletrificada e ligada durante a noite. De manhã, os guardas desligavam a eletricidade. Certa manhã, esqueceram-se. Um prisioneiro que estava a varrer o chão perto da vedação tocou-a acidentalmente e foi eletrocutado. As pessoas que trabalhavam com ele, vendo o que tinha acontecido, correram para a guarita para pedir aos guardas que desligassem a energia, mas quando voltaram, o pobre coitado já estava morto. Esqueci-me do nome dele, embora fosse um bom amigo. Penso que trabalhou com o Alex Azedo na Optorg & Co.

No campo, aprendemos a fazer as nossas próprias camas. Havia inspeção japonesa todas as manhãs. Cozinhávamos muita coisa, mas principalmente com óleo e molho de soja no nosso chow-fan (arroz frito). Martelávamos pregos para prender as tiras dos tamancos, remendávamos meias e costurávamos botões. Uma mulher inteligente casaria com um ex-prisioneiro de guerra. (A minha mulher não tinha nada para fazer com os empregados; por isso, aprendeu a jogar mahjong e agora está totalmente ocupada.)

Sempre que lavávamos a roupa, pendurávamo-la no arame, pegávamos numa cadeira e num bom livro e esperávamos até que secassem. Se não, alguém poderia bater-lhe à porta, tentando vender-lhe as calças ou a camisa que tinha acabado de lavar! Se as suas roupas estivessem demasiado velhas para serem roubadas e vendidas, o conselho era esperar pela chuva e pendurá-las no estendal. Mais tarde, o sol surgiria e secá-las-ia.

A latrina ficava a cerca de 800 metros das cabanas e queixámo-nos às autoridades sobre a longa caminhada à noite, especialmente no inverno. Pela primeira vez, os japoneses compreenderam e permitiram que cada um de nós tivesse uma lata. Urinávamos, colocávamos a lata debaixo do tapete e depois levávamos para a latrina de manhã. Como é que fizemos. Esvaziámo-los pela janela.

Certa noite, um dos prisioneiros de guerra encheu a sua lata e atirou-a pela janela do vizinho. Mas a janela estava fechada e a urina espirrou para cima dele. O criminoso fingiu estar a dormir quando ouviu o vizinho murmurar: “Uau, está a chover. Engraçado, as janelas estão fechadas – o teto deve estar a pingar.” O vizinho colocou um balde perto da cabeça dele e voltou a adormecer.

Os japoneses trouxeram muitos equipamentos desportivos para os prisioneiros usarem nas horas vagas. Jogávamos basebol, futebol, hóquei, ténis, voleibol e até boccia, mas o boccia não durava muito tempo, pois jogávamos na areia. O pouco de erva era reservado aos fumadores, que só descobririam duas décadas depois que também fumavam canábis. Éramos apenas prisioneiros. Alguns dos rapazes aprenderam também bridge e xadrez.

Um dia, os japoneses desafiaram-nos para jogar basebol. Formamos uma boa equipa. Quando um certo japonês chegou para rebater, muitas vozes gritaram: “Vá lá, apanhem este tipo.” Largou o taco e perguntou: “Quem disse isso?”. Ninguém respondeu. Mas nós eliminámo-lo.

A alcunha deste tipo era “Slap-Happy” (feliz tapa). Um nipo-canadiano, que andava por aí a esbofetear as pessoas sem qualquer motivo. Foi enforcado depois da guerra e mostrou-se muito arrogante no julgamento, mas não foi páreo para Marcus da Silva, que era o procurador.

Naquela época, quase toda a gente fumava. As placas de “Proibido Fumar” eram raras. Cigarros como Camels, Lucky Strikes, Capstan, etc., eram populares. Mas, à medida que a guerra avançava, estes cigarros importados tornaram-se cada vez mais raros no campo e eram valorizados. Os cigarros eram trocados por outras mercadorias desejadas. Na verdade, fumávamos qualquer cigarro – agulhas de pinheiro, folhas de chá, erva – o que se quisesse.

Também tínhamos cigarros japoneses, que eram muito fortes. Uma passa deixava-o tonto. Nós chamávamos-lhes “assassinos” e “estrume de vaca”. Ao oferecer a alguém um destes cigarros japoneses, dizíamos: “Toma um estrume de vaca”.

Um dos kwai-lohs do acampamento costumava aproximar-se de si enquanto fumava e dizer: “Dá-nos um isqueiro, amigo”. Depois via o seu cigarro a ficar cada vez mais curto. Este tipo tinha um pedaço de papel oco e estava a fumar o seu cigarro. Ficámos zangados, mas também aprendemos com este truque.

Nanelli Baptista, artista e fumador inveterado no Natal, fazia um cartão de felicitações por três cigarros. (Troquei um par de luvas de malha por cinco cigarros). Naneli tinha tantos pedidos que tive de o ajudar e quase me tornei um fumador inveterado.

Todos os natais, fazíamos votos um ao outro e esperávamos ver todos lá fora no Natal seguinte. Com o passar de mais dois Natais no acampamento, as nossas esperanças diminuíram.

Negociação fora da vedação do acampamento

Apesar da vida sombria no campo, havia momentos mais leves. Costumávamos comprar algumas provisões de fora. No início, comprávamos bolos chineses por um dólar, mas depois os bolos diminuíram de 12 centímetros de diâmetro para 2,5 centímetros, de modo que conseguiam passar pela vedação quando havia apenas alguns guardas por perto. Levava-se o bolo num “um-dois-três”, enquanto o vendedor do lado de fora levava o dinheiro simultaneamente.

Certa vez, um prisioneiro de guerra rasgou uma nota de um dólar ao meio e comprou um saco de açúcar dessa forma. O prisioneiro ficou com o açúcar e o chinês que estava do lado de fora da vedação foi enganado com meio dólar. O prisioneiro riu bastante. No dia seguinte, foi novamente caçar com a outra metade do seu dólar. Mas desta vez, o vendedor chinês com o açúcar estava disfarçado e, quando se chamou “um-dois-três”, levaram o dinheiro simultaneamente. O vendedor tinha agora a outra metade do seu dólar, mas o prisioneiro de guerra recebeu o castigo com apenas um pacote de areia!

Um dia, a minha mãe enviou-me um mamão papaia e, como o dia seguinte era domingo, guardei-o para um lanche de domingo com uns amigos. Com medo de ratos forrageadores, amarrei as pontas do mamão papaia com um fio comprido em pregos de ambos os lados da sala, balançando-o no meio. Como poderia eu imaginar que aquele ratinho (ou grande) era um equilibrista? De manhã, encontrei um furo perfeito no mamão papaia. Não importa. Cortei à volta do buraco e partilhei a sobremesa com os outros.

Na nossa cabana, durante algum tempo, ouvíamos aquele barulho de chomp-chomp no telhado todas as noites. Não nos incomodava, mas um menino da mamã queixou-se ao padre que achava que a cabana estava assombrada, então o padre trouxe água benta e abençoou a cabana. Mas o chomp-chomp continuou. Uma noite, ouviu-se o barulho habitual, e bingo, um rato enorme caiu de um buraco no tecto, mas saiu a correr da cabana, demasiado rápido para que o pudéssemos apanhar.

Os prisioneiros de guerra casados e mais velhos preocupavam-se constantemente com as suas esposas e filhos que estavam no exterior. Nós, os mais novos, entre os 20 e os 30 anos, fazíamos o possível para ajudar estas pessoas casadas, brincando e contando histórias engraçadas. Graças a Deus, ouviram e juntaram-se à turma.

Incentivadores da moral

O moral dos homens no campo foi elevado pela música e pelos espetáculos produzidos pelos reclusos. O falecido Johnny Fonseca, muito popular no campo e conhecido até pelos prisioneiros de guerra ingleses e canadianos, fez muito pelos nossos rapazes com a sua guitarra. Ele acompanhou-nos enquanto cantávamos com alguns kwai-lohs a juntarem-se.

Tivemos também concertos pelos quais todo o crédito deve ser dado a Nanelli Baptista, aos seus ajudantes e ao pessoal dos Royal Engineers pela cenografia; ao Eli Alves, Reinaldo Gutierrez e [Mario Francisco] Alarcon pela sua doce música de violino; às “meninas” – Sonny Castro (que se vestiu de Carmen Miranda), Eddie e Gussy Noronha, Robert Pereira e alguns outros. (Não se podia dizer que não eram raparigas a não ser que as despissem!)

O comandante do campo japonês, a sua comitiva e alguns amigos de fora costumavam assistir a estes eventos, ocupando as três primeiras filas do teatro improvisado, chegando em limusinas, enquanto nós os olhávamos como os fãs de cinema admiram as estrelas quando chegam para a cerimónia dos Óscares em Hollywood.

Antes de falar de George Ainslie [Soldado 2841], um bom amigo que, aos 18 ou 19 anos, foi o nosso prisioneiro de guerra mais novo em Shamshuipo, preciso de divagar: ele e eu (e outros) costumávamos mergulhar juntos no antigo Victoria Recreation Club (V.R.C.), na orla de Hong Kong. No início, mergulhávamos da prancha inferior de um metro, depois da prancha de três metros e, por fim, da varanda para a piscina. Não conseguíamos ir mais alto, por isso mergulhávamos da janela da sede do clube para o mar. Finalmente, fomos parar ao telhado do prédio e olhamos para baixo. Tudo o que conseguimos dizer foi “Jeepers”, por isso descemos, mas um dos rapazes escorregou e caiu no mar. Foi então que vimos a enorme multidão na marginal a dar um espetáculo gratuito. Mas o espetáculo tem de continuar.

A altura era assustadora; cerca de sete andares, e para aumentar o perigo, a água em baixo era relativamente pouco profunda, uma vez que a maré estava baixa. Os nossos corações devem ter parado quando demos o mergulho, que aparentemente demorou muito tempo a chegar à água. Mas todos nós: Eddie (Macaco) Roza, Lionel Roza-Pereira, Peter Rull, Manaelly Roza, Hugo Ribeiro e um tipo chamado Pullen [William P, Marcador DR284], fizemos o mergulho. Fiquei com torcicolo durante uma semana. Agora, de volta ao campo de Shamshuipo.

George Ainslie morreu de difteria no campo de prisioneiros e Pullen morreu na guerra. David Hutchinson [Soldado 3552] era o sujeito com sarna e desmaiou quando lhe esfregaram as costas. Era muito simpático com os nossos rapazes, pois era membro do VRC e campeão de natação de 100 jardas da Colónia. (Depois da guerra, foi para a Austrália, casou com uma australiana católica, tornou-se católico e ia à missa todos os dias. Tenho a certeza de que muitos de nós não vão à missa todos os dias — pelo menos eu — mas se disser que há um jogo de mahjong às 6h, aposto que muitos de nós acordarão às 5h).

Recrutados para ir ao Japão

Um belo dia (em agosto de 1944), saímos para uma equipa de trabalho e, quando regressámos (a Shamshuipo), às 18h00, o comandante do campo japonês e alguns dignitários esperavam-nos no campo de futebol. Estavam ali para escolher os homens mais aptos para irem para o Japão. Fizeram-nos andar pelo campo, não se conseguiram decidir e finalmente disseram: “Todos para irem”.

Fomos colocados num dos lados do campo, separados dos outros prisioneiros por arame farpado. Fizemos um buraco no arame farpado e saímos para conversar com os nossos amigos, regressando à noite para dormir. Um sujeito quase foi apanhado pela sentinela japonesa. Correu e saltou a cerca. O guarda disparou, mas falhou. Era o Zinho Gosano.

Os médicos e especialistas japoneses estavam lá todos os dias para nos aplicar injeções, recolher amostras e fazer outros exames. Penso que eram uns 20 no total. Teria de ficar na fila, fosse a sua vez hoje ou amanhã. Um sujeito opôs-se à inserção de uma pequena vareta de vidro no seu traseiro para extrair uma amostra de fezes através da expulsão de gases no momento crítico. O médico deu o máximo de si e mostrou a este sujeito que estava realmente furioso. É um milagre que tenha sobrevivido à palmada.

Um navio anterior que partiu do nosso acampamento com soldados para o Japão a 27 de Setembro de 1942, a maioria homens dos Regimentos Royal Scots e Middlesex, estava no Lisbon Maru, que foi afundado por um submarino americano, o U.S.S. Grouper, com a perda de cerca de 1.000 prisioneiros de guerra aliados. A maioria foi metralhada pelos japoneses quando, presos no porão do navio que afundava, os prisioneiros tentaram subir ao convés para se salvarem. [Para a fonte definitiva, ver: “The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain’s Forgotten Wartime Tragedy” de Tony Banham, Hong Kong University Press, 2006 – Ed.]

Íamos conhecer outro país e não estávamos descontentes, pois tínhamos viajado apenas até Macau anteriormente. Perigo naquele momento nunca nos passou pela cabeça.

Fomos o segundo grupo a ser enviado. [A pesquisa mais recente mostra que foi o quarto de cinco contingentes de prisioneiros de guerra enviados para o Japão como trabalhadores escravos – Ed.] O primeiro grupo foi enviado para as docas em Toyama, no Japão, no início do ano.

A lista, abaixo, de homens macaenses no Corpo de Defesa Voluntário de Hong Kong que foram enviados para as minas de carvão no Japão: [Atualizamos a lista do autor com informações de um site mantido pelo “Centro de Pesquisa, Prisioneiros de Guerra Aliados sob o Comando Japonês para o Estudo Detalhado de Guam e todos os Prisioneiros de Guerra Aliados usados como Escravos pelos Japoneses na Segunda Guerra Mundial” e outros sites – Ed.]