SÃO PAULO

Henry d'Assumpção

Macau’s most famous landmark is the façade of the Church of the Mother of God (Madre de Deus), which is today commonly called São Paulo (St Paul’s church). It is all that is left of what was once the outstanding baroque structure of Eastern Asia. An earlier church was first constructed on the site in 1580, which was burned in 1595 and destroyed by fire in 1601. Reconstruction of a magnificent new church began in 1602, which was not completed until 1644. It was part of an complex including a college – the first in Western Asia – and a large library that was considered the most valuable in South-East Asia.

S. Paulo was an imposing structure, 37m long, 20m wide and 11m high with an ornate granite façade facing south and a broad flight of 66 granite steps, and would have dominated the landscape of old Macau, and made an impressive sight to all vessels going up the Pearl River to Canton (Guangzhou). It is described in a Jesuit report, written in 1644 on the completion of the church. The newly-built church is described in a 1644 report:

It has been suggested that it was modelled on the Chiesa del Gesù (Church of Jesus), the Mother Church of the Jesuits, but this has been questioned.

Originally, the church had three large halls built of white stone and an imposing vaulted ceiling. The main altar had four statues of Jesuit saints. The internet blog Classical Iconoclast, states that the walls were made of chunambuco (a mixture of shells, stones, and clay) and richly decorated with paintings, ivory, gold, and silver.

The church, school, and library were destroyed by a disastrous fire during a typhoon in 1835, leaving only the granite facade and stone steps.

The artisans who worked on the church were Japanese Christian refugees from Nagasaki, fleeing religious persecution under the Tokugawa regime. Its architect was an Italian Jesuit priest, Father Carlo Spinola (1564–1622). It seems unlikely, as some articles claim, that he oversaw the construction of the church, as he spent most of his time as a missionary in Japan, operating underground to escape persecution for four years, until he was captured and martyred, 22 years before the church’s completion. Most likely, the facade decorations were done under the supervision of another Italian Jesuit, Giovanni Nicolao da Nola.

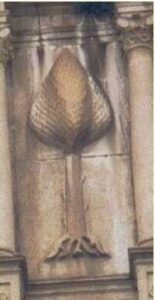

At the centre of the third tier is a statue of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, with a frieze of chrysanthemums (representing China) and peonies (representing Japan), standing on a large (originally gilt) moon (clearly a reference to the Entrance Antiphon of the Feast of the Assumption: ‘A great sign appeared in heaven: a woman, adorned with the sun, standing on the moon …’ Revelation 12:1). She is surrounded by angels with incense and trumpet. On her left are carved bas-reliefs of:

a seven-headed monster with an image of the Virgin Mary above one of its heads and the inscription ‘The woman crushes the dragon’s head’ (Reference: ‘Then a second sign apeared in the sky, a huge red dragon which had seven heads … ‘ Revelation 13:1 and ‘I will put enmity between you and the woman, between your seed and her seed. It will crush your head … ‘ Genesis 3:15)

It is interesting that the bronze statues (and many of the cannons of the fortifications of Macau) were cast in a foundry in the settlement.

At one stage the structure was leaning dangerously and there were calls for the ruins to be demolished but these were fortunately resisted. Archaeological excavations at the site, from 1990 to 1995, uncovered the crypt and foundations that revealed the architectural plans of the building. The ruins were restored by the Government of Macau, with the façade buttressed for protection.

In 2005 the ruins of S. Paulo were listed as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Historic Centre of Macau so they will be protected for posterity.

See also The Ruins of S. Paulo

SÃO PAULO

Henry d'Assumpção

A Igreja de São Paulo era uma estrutura imponente, com 37 m de comprimento, 20 m de largura e 11 m de altura, com uma fachada ornamentada em granito virada a sul e um amplo lanço de 66 degraus em granito. Dominava a paisagem da antiga Macau e impressionava todos os navios que subiam o Rio das Pérolas até Cantão (Cantão). É descrita num relatório jesuíta, escrito em 1644, após a conclusão da construção da igreja. Leia o relatório

O marco mais famoso de Macau é a fachada da Igreja da Mãe de Deus (Madre de Deus), que hoje é vulgarmente chamada de São Paulo (Igreja de São Paulo) 1. É tudo o que resta daquela que foi outrora a mais notável estrutura barroca da Ásia Oriental. Uma igreja anterior foi construída no local em 1580, que foi incendiada em 1595 e destruída por um incêndio em 1601. A reconstrução de uma nova e magnífica igreja começou em 1602, sendo concluída apenas em 1644. Fazia parte de um complexo que incluía uma faculdade – a primeira na Ásia Ocidental – e uma grande biblioteca, considerada a mais valiosa do Sudeste Asiático.

Sugeriu-se que foi modelada na Chiesa del Gesù (Igreja de Jesus), a Igreja Matriz dos Jesuítas, mas isso tem sido questionado.

Originalmente, a igreja possuía três grandes salões construídos em pedra branca e um imponente teto abobadado. O altar-mor possuía quatro estátuas de santos jesuítas. O blogue Classical Iconoclast, afirma que as paredes eram feitas de chunambuco (uma mistura de conchas, pedras e barro) e ricamente decoradas com pinturas, marfim, ouro e prata.

A igreja, a escola e a biblioteca foram destruídas por um incêndio desastroso durante um tufão em 1835, restando apenas a fachada de granito e os degraus de pedra.

Os artesãos que trabalhavam na igreja eram refugiados cristãos japoneses de Nagasaki, fugindo da perseguição religiosa sob o Regime Tokugawa e chineses locais. O seu arquiteto foi um padre jesuíta italiano, o Padre Carlo Spinola (1564-1622). Parece improvável, como afirmam alguns artigos, que tenha supervisionado a construção da igreja, dado que passou a maior parte do seu tempo como missionário no Japão, operando clandestinamente para escapar à perseguição durante quatro anos, até ser capturado e martirizado 22 anos antes da igreja estar concluída. Muito provavelmente, as decorações da fachada foram feitas sob a supervisão de outro jesuíta italiano, , Giovanni Nicolao da Nola.

No centro do terceiro nível está uma estátua da Assunção da Virgem Maria, com um friso de crisântemos (representando a China) e peónias (representando o Japão), de pé sobre uma grande lua (originalmente dourada) (claramente uma referência à Antífona de Entrada da Festa da Assunção: ‘Um grande sinal apareceu no céu: uma mulher, adornada com o sol, de pé sobre a lua…’ Apocalipse 12:1). Está rodeada de anjos com incenso e trombeta. À sua esquerda estão esculpidos baixos-relevos de:

um monstro de sete cabeças com uma imagem da Virgem Maria por cima de uma das suas cabeças e a inscrição ‘A mulher esmaga a cabeça do dragão’ (Referência: ‘Depois apareceu um segundo sinal no céu, um enorme dragão vermelho que tinha sete cabeças…’ Apocalipse 13:1 e ‘Porei inimizade entre ti e a mulher, entre a tua descendência e a tua descendência. Ela esmagará a tua cabeça…” Génesis 3:15)

É interessante notar que as estátuas de bronze (e muitos dos canhões das fortificações de Macau) foram fundidos numa fundição no povoado.

A dada altura, a estrutura estava perigosamente inclinada e houve pedidos para que as ruínas fossem demolidas, mas felizmente não foram atendidos. Escavações arqueológicas no local, entre 1990 e 1995, revelaram a cripta e os alicerces que revelaram os planos arquitetónicos do edifício. As ruínas foram restauradas pelo Governo de Macau, com a fachada reforçada para protecção.

Em 2005, as ruínas de São Paulo foram listadas como parte do Centro Histórico de Macau, Património Mundial da UNESCO, para que sejam protegidas para a posteridade.

Veja tambem Ruínas de São Paulo