THE LIFE AND TIMES OF FATHER JOSÉ “ZINHO” GOSANO

First published in the UMA Bulletin Apr-Jun 2011 Vol 34 No 2

[Editor’s Note: A number of years ago the late Fr Zinho Gosano’s friend in New Zealand, a Father John Griffin, sent the UMA News Bulletin editor a floppy diskette containing an autobiographical narrative by Fr Gosano. It was originally made for Father Hayes who was to publish an article in a Military magazine after the 50th POW reunion in Hong Kong in 1991. Recently rediscovered, the story of Father Gosano’s life and times makes interesting reading, particularly for those of the Macanese Diaspora who were raised in Hong Kong in the middle years of the last century, and for whom the experiences of World War II left an indelible mark. It also has significance for the younger generations whose own appreciation of what their parents and grandparents underwent during those years may be broadened by one young man’s personal story.

This edition begins with Father Zinho’s early life and the family to which he was deeply devoted, his exploits as a skilled sportsman in Hong Kong before WWII, his service in the defence of Hong Kong at the time of the Japanese attack in 1941, his subsequent internment as a prisoner-of-war in Shamshuipo camp, Hong Kong, and the time he spent, alongside other POWs, doing forced labor in a coal mine in Sendai, Japan. His account continues with the aftermath of the War and his rehabilitation from his wounds in a New Zealand hospital, a sojourn in the United Kingdom, and his decision to join the priesthood as a direct result of his three close brushes with death during the War.

His story is presented here much as he narrated it, with changes or some inconsistencies in syntax, proper names, punctuation, and rearrangement into logical order.]

MY FAMILY

The Gosanos were a well-known Portuguese family. Mother was of Portuguese parentage. Her parents, named Marques, came from Macau and settled in Hong Kong.

My retired as a major in the Portuguese Forces. My was baptised and grew up in Macau and came to Hong Kong to look for a job. There he met my and they got married in the Cathedral so most of us were born in Hong Kong Island not far from Happy Valley. There is a church there called St. Francis Church where we were all baptised.

The small Portuguese community in Hong Kong came to know one another very well. We had a club – Club de Recreio – where we played our sports.

We grew up as a very close-knit, united family. There were 9 in the family, 7 boys and 2 girls -I was the youngest. In the house we had 2 or 3 Chinese servants, so I grew up with Cantonese and Portuguese in the family; English came in quite simply so I had 3 languages.

My father died when I was 3½ months old, drowned accidentally at sea. My oldest brother A.V. (or as he was known to all in Hong Kong) looked after me.

We had a wonderful family life – besides the 9 of us plus Mother, and we had 2 of Mother’s brothers living with us. Mother was also looking after another 4 orphans – her brother’s children (a boy and 3 girls), and then another family of my mother’s also tended to stay with us including 2 boys. So we had a tremendous family, about 18 or 19 at one stage. That family life was how I was bought up, full of love and unity, all looking after one another. I suppose being the last born I was a little spoilt – my brothers were very good to me.

About 1932 we went to Homantin and bought a two-storey house there. We still had quite a few of the family with us. Besides Mother and the nine of us children, our cousins Roberto and Vancy and my Uncle Afino were there, though the other cousins, the three girls and a boy, had left us. There were about 15 or 16 in the house and it was great fun. The new suburb was good and not crowded. We lived on Soares Avenue, Homantin, where there were quite a few Portuguese people who had bought the houses around us. Two Portuguese families who lived there were named Gutierrez and Yvanovich. We had a great crowd of young people who enjoyed great times together.

In those days we were still in school, but some of us who had left school still gathered around with this crowd. The St Theresa’s Church was only a mile away; the girls went to the Maryknoll Convent taught by the American Maryknoll Sisters and we boys had La Salle College about a mile away. Growing up in a very congenial society, we spent much time with one another.

School work was not difficult as I always was very attentive at class – learning everything in school and doing the homework. It didn’t make any difference if you were Portuguese, Chinese, Indian or Jewish because I remember at La Salle college I had two other very good friends: John Arculli and Robin Prish. I was a Portuguese, John was an Indian, and Robin was a Jew. We were doing our matriculation in 1938/39 and in those days as you start to get to a senior class of the college, you realise too that it won’t be long before you go to work out in the world.

I recall a very nice girl in the Maryknoll Convent who used to stand around the entrance of the girls’ school as we came passing from the boys’ school. We used to meet and chat – there was attraction, I suppose. The girl used to ring when I wasn’t home, and Mother would recognise her voice and tell her off for ringing me too much.

We lived on the left side of the road going up towards Kowloon Tong. Where today there are so many multi-storied buildings, in those days in 1932 there were just small hills and paddy fields, and the main road where they were building new homes, not very far from where the new Saint Theresa’s Church was just built. Not very far from Saint Theresa’s Church, a new college was being built called La Salle College. The College was located way up on a hill – it took about 70 steps from Boundary Street up to the big building where the secondary college was. It was run by the Christian Brothers. My brothers , and I used to walk to school every day. The walk took a half-hour.

It is during this time the third brother in the family, , who was then about 22 or 23 and working in the Bank, fell ill. One of the Bank doctors, an Englishman, came to look at him and said he might have some signs of lung trouble but he couldn’t diagnose Carlinho’s problem. My brother was then studying to become a doctor at University and it was he who thought Carlinho did not have what the doctor thought, so he insisted that we get a second opinion from a Chinese doctor, a graduate from Hong Kong University, who was working in Kowloon Hospital not very far from our house.

This Chinese doctor came to look at Carlinho and said he might have typhoid fever. Our mother was very anxious and called for another Chinese doctor to treat Carlinho in the Chinese way. He used some powder and said that Carlinho was suffering from typhoid fever. Unfortunately it was too late, Carlinho was in a coma. The doctor put him in Kowloon Hospital for observation, and that very night he died. It was my first experience of someone I knew so well passing away. His death affected the whole family because he was the first of the boys to die. My mother said he was the most handsome of the family.

He had a girlfriend Pam Yvanovich who lived just down the road from us. She was the eldest of the girls in that family. My sister and Pam used to go around together and that’s probably how Carlinho met her at home and fell in love with her and they were engaged to be married. My other brother helped her get over the loss of Carlinho, looked after her and married her in 1940; they later had five boys and a girl.

The house in Soares Avenue was two-storied. It was attached to number 9 Soares Avenue which was occupied by a Portuguese family, the Sequeiras. Next door to us, number 13, was occupied by another Portuguese family called Barros. In between this house and the next was one also occupied by a Portuguese family called Guterres. Next door to the Guterres’ was where the Yvanovichs lived and that was the family which Pam came from. We weren’t very far from her. It was good we were close together and there again we had a whole lot of young people who formed a very good and happy group. We used to have great fun together going out swimming and on picnics. In a crowd like that you were always in very good company. We were a young healthy bunch of people. I was the youngest of that group of girls and boys in the street who played rounders, tennis, went hiking – all those things young people would do together.

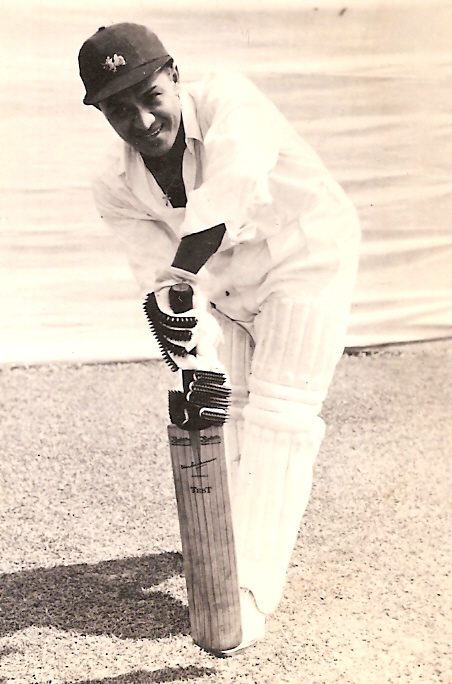

I wasn’t very keen on night life. My older brothers were good sportsmen. Every time they had a game we would go and watch them – cheering for them, following them and watching them play. Eddie was playing cricket at University. He became quite a good player and played for Hong Kong – because of him Gerry and I also started playing cricket and we formed a team at school and also played combined schools and we started making names for ourselves as good cricketers.

We also played hockey, tennis and swam and played soccer for the school. Our whole life was geared around sport – we did the usual studying but nothing you would get scholarship for. It was enough just to pass from one class to another.

I became an altar boy, serving mass at the Church and going to mass in the morning with my mother – coming back, having breakfast and going to school. It was a very healthy life, full of sports, lots of happiness at home. Gerry and I were like twins. In fact, I was going to be bigger than Gerry. He was not very keen on studying – one class separated us and he was two years older than I. He was one of the best sportsmen in Hong Kong in the Portuguese community, a good runner, cricketer, hockey player, tennis player, softball player, very good swimmer. He was someone every young Portuguese player would aspire to be.

Mother always bought us up properly and made sure that we went to mass every Sunday. She would bang on the door ever and say “Come on, it’s 20 minutes to 9”. We used to attend 9 a.m. mass at St. Theresa’s Church a mile and a half away, then straight to Club Recreio where we played hockey at 10.30, and softball at 1.30. On Saturdays between one and six in the afternoon we played cricket so we were as fit as a fiddle all the time. Our time was filled with sporting activities. We never took an interest in women, or drinking, or smoking – we were too young for all that.

SPORTS

In the middle of 1938 the results of the school certificate came through. Both Gerry and I passed the school leaving exam. This meant that we could start to work or alternatively study for matriculation. My mother felt it was alright for Gerry to go to work but I was only 15 and she felt I should go back to school to study for my matriculation. I was quite happy about that – I preferred to study than go to work. I was the only one not working and so I took the opportunity to go back to school and be in the top class at La Salle College. We had a great year of studies and sport.

I was very interested in cricket and used to go with the first team of Club de Recreio. Eddie by that time had graduated and was working in Kowloon Hospital. Luigi, Eddie and Gerry were all playing for Club de Recreio; Lino and Bertie were playing soccer. I was very keen on cricket myself after having played for La Salle College first eleven and was also picked to play against the combined schools first divisions in Hong Kong. I used to go as a scorer for the team as I watched the Portuguese boys playing against the others. I enjoyed keeping the score book and used to go to all the games. During weekdays I used to go to the nets and bowl for the players and showed signs of being quite a good cricketer. In March or April 1939 the Recreio team had a chance of winning the First Division Cricket League but they didn’t have an opening batsman so they asked me at one of the games at our club if I’d play for the team. The Captain, Dr. Albert Rodrigues , wanted me to play for the team too.

I told Mother about it – the fellows wanted me to play for the club because there was a chance of the Portuguese team winning the league for the first time. Mother hesitated and felt I was too young to be a member of the club (I was 15½ at the time).

She felt I should finish school first because if I played for the club I would have to pay a membership fee. My brother Lino was sitting to one side and didn’t say much. So I said if I get a job I could pay for my fees. Mother said it was up to me. All the other brothers wanted to pay for my membership but I wouldn’t let them.

My mother reminded me that I was only two months from my matriculation exams and if I passed I could go on to University. But at that stage I wasn’t very keen on studying: I was more enthusiastic about playing cricket. I went back to the club and told them my mother had said I couldn’t become a member unless I got a job and paid for my own membership so they offered to help me get a job. The very next day I received a call from one of the players who worked for the Dutch Bank. He informed me he had a job for me and told me to come and see if I liked it. He said, “You can talk to the Chief Clerk and maybe he’ll sign you up for the bank.” The Chief Clerk turned out to be one of the Portuguese boys there so straightaway when I went in I said “I hear you’ve got a job for me.” He showed me the mailing and filing department which was a one-man department. The fellow leaving gave me an introduction to the job. So I said OK, I would take the job. That very first Saturday I played for the Club for the first time – opening batsman for the first eleven. It was great.

That’s how I started working because of my love for cricket. What a mad thing when I think of it now. But that was life in the past and I didn’t regret it at all because I started working and I was paid along with everyone else at home. I paid my way from then onwards. No one was to realise that year, 1939 was the beginning of War in Europe and England was involved.

OUTBREAK OF WAR

The downturn came with the withdrawing of British forces back from France. The British of Hong Kong were all conscripted and, being British subjects, the Portuguese people thought we should join the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps. So quite a lot of our Portuguese boys in Hong Kong joined up and formed a Portuguese Company. We had two companies then – a machine gun company and a Lewis gun company, which became respectively the 5th and the 6th in the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps.

All my brothers joined up. I had already done my matriculation by that time and was working at the Nederlandsche Indies Handels Bank in Queen’s Road. I was only 16½ but was bigger than my older brother so I could quite easily pass for 18. I signed in with my brother Gerry who was 18. When they asked me my age I said was born on the 11th of July 1923. The Portuguese lieutenant who was signing us up told me I was too young and I was a bit downcast. Back at home my brother Lino asked how I had got on. I explained that I had given my age and was told I was too young. Lino asked how many officers were there to sign up and we said 3 of them, and that Gerry and I had gone to number 3. “Oh, in that case,” Lino said “go to number 1 tomorrow and just tell him you were born in 1921”. So that’s how I joined up in 1939. (And strangely enough when it came time for them to give me a record of my time as a prisoner of war, they couldn’t give me my date of entry into the service. I was demobbed in England in 1947.)

We joined up because we felt if anything happened we should fight for Hong Kong. So this was the beginning of the volunteers in Hong Kong. We were trained in small arms. I was in the Machine Gun Company. Luigi, Gerry, Bertie and Lino were in the Lewis Gun Company, and Eddie was in the Medical Corps.

Nobody realised at that stage there was going to be a War in the Far East. We never thought about it. We were doing all sorts of sports – swimming, running, hockey, cricket, softball, baseball. We raised money to send to England so that we could have a bomber squadron in the name of Hong Kong. It showed the tremendous unity among the people of Hong Kong and loyalty to Britain. We did quite a lot as far as coming up to the standard of sports and also in sending the money to Britain. At that stage we never thought the Japanese were going attack Hong Kong.

JAPANESE INVASION

I was then 18 years old when the Japs came in December 8, 1941. I had already done all my training with the Volunteers in the No. 5 Machine Gun Company but we didn’t have any machine guns – they had all been sent to North Africa – and we were only issued with Lewis guns. My brothers Gerry and Luigi were in the No. 6 Lewis Gun (Antiaircraft) Company. (Our older brother Lino also was in the Volunteers broke his leg playing soccer and couldn’t go to the War.) The Lewis gun was quite a good gun but you can imagine how it would go trying to shoot down Zero fighter planes flying at speed.

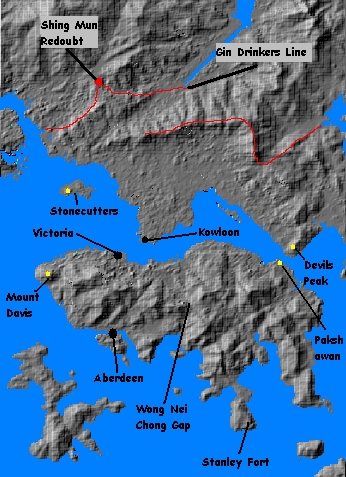

[Editor’s note: The Japanese 38th Division invaded Hong Kong on December 8, 4 hours after their attack on Pearl Harbor. The British defences in the New Territories (along the Gin Drinkers Line) were weak and undermanned and the Japanese rapidly broke through them. On the night of December 12 the British evacuated their forces from Kowloon to Victoria Island.

On December 18 the Japanese got crossed the water at Lye Mun Pass and drove towards Wong Nei Chong Gap with the intention of cutting the British forces in two. Fr Zinho Gosano’s account continues …]

The Japanese came through Lyemun Pass down Big Wave Bay and towards Stanley; another wing came through Wongneichong Gap and attacked the main part of Victoria, the capital of Hong Kong. Certainly their frontline troops – all crack troops – were very good. They had been fighting the Chinese since 1931. It’s not that they had very many men but they had enough to wipe us out and we certainly couldn’t do much about it as we didn’t have enough men or equipment. We on the other hand had never seen war before – we had done a lot of practising, a lot of exercising – but nothing compared to the real thing which was quite frightening.

We were fortunate that the Portuguese forces were not on the Eastern side of the Island where the Japanese forces landed. There were three Portuguese companies positioned to defend Mount Davis. Our two Portuguese companies were defending the Forts near Shouson Hill (around the Island towards Pokfulam). My platoon was in Pokfulam Rd and Gerry and Luigi were up around Queen Mary Hospital on that road.

There were three 9.2-inch guns at the top and of Mt Davis, pointing out to sea where we were expecting an invasion from but the Japanese came overland from Lo Wu. We could see them in Kowloon but could do nothing. The armour piercing shells from the 9.2 guns were intended for battle ships or cruisers, not land targets.

Luigi D’Almada Remedios and I (he was the section corporal and I was the gunner) were in a little foxhole by the side of the road just across from the garage when the Japs dropped bombs on us. One fell 5 yards from where we were, but we were below surface of the road, thank God.

This bomb fell on Luigi’s side – I was on his right and he was between me and the bomb. I was blown out of the foxhole about 25 yards down the slope and Luigi was buried in the very crater of the bomb. When I shook my head after the dust had settled I shouted to the fellows in the garage: “Where’s Luigi? Dig Luigi out; he’s probably in the hole of the crater.” The right side of his body was paralysed, his mouth drooped and his eyes went crooked. He was bundled up to a stretcher and taken to Queen Mary Hospital. They were horrific injuries but this man is still alive and in Seattle – I have stayed with him.

The bomb crater extended all the way to the garage and its door was blown open. I could have been killed but nothing happened to me – all I lost was a shirt that was torn to bits.

We expected the Japs to come from Pokfulam and we had heard they were forcing their way down Wongneichong Gap towards Repulse Bay; another arm of the attacking force was coming along Lyemun Pass going through Sai Kung and Deep Wave Bay to Stanley.

When the Japanese fought the Chinese they never took any prisoners. However they did spare some of the fellows who were overcome but most of the pillboxes in Wongneichong Gap and all along the naval dockyard and all the batteries to Stanley were wiped out and not many of them survived. The Japanese used to make sure all of them were dead by shooting them but some men survived by playing dead.

One of the Eurasian Companies (Third Machine Gun Company) in Wongneichong Gap – I had played cricket with many of their fellows from Kowloon Cricket Club – lost three-quarters of their men. One family lost four boys in Wongneichong Gap. We were very fortunate to have survived.

There were 11 or 12 miles of beach in Kowloon covered with Japanese Forces waiting to come across if Hong Kong did not give in, but thank God Hong Kong fell: the armistice was signed on Christmas day.

Because of the difficult line of communication it didn’t immediately become apparent that Hong Kong had surrendered. We finally received a dispatch rider at Mt. Davis who came to tell us to pack up and go back to the old Volunteer Headquarters and to group there as the war was over – we had capitulated. It was a great relief as we went to pack up we looked at one another and said well at least the War is over for us. But they were still fighting at Stanley on the 26th, the day after the armistice.

We didn’t know much about anything – that so many people had been killed and that the Japanese had taken over the whole of Hong Kong. I had 3 brothers in the heavy fighting and at that stage I didn’t know Bertie had been taken to hospital with shrapnel in the back.

It was a relief to get away from the bombing and killing. We didn’t foresee so many years of prison camp – just as well we didn’t know much about it at that time.

PRISONER-OF-WAR IN SHAMSHUIPO

So we packed up our things and trucks came and took us up to Murray Barracks at Mid Levels where the Army Forces had been garrisoned before the war. We stayed there for one night and waited for the rest of the company to come together.

My section corporal and two of us were wandering around the Barracks looking for food and in one of the rooms found many cartons of food stacked up in a corner. We helped ourselves, opened some cans of meat, vegetables, and fruit and had a good feed sitting on top of the cartons.

Some of the boys throughout the day decided to take off. One of the section corporals left and he actually got away from Hong Kong, got to Britain and joined the RAF; the other one went home and stayed with his people. I waited for my brothers Luigi and Gerry and when they came we said “What are we going to do about it? Shall we go too?” As we didn’t know where our mother and sisters were we decided to wait. Our company commanders came back and said we had better stay otherwise the Japanese would find out who we were and take it out on our people. So we waited.

The orders came, we packed our kitbags, took a few tins of food, took the ferry over to Kowloon and started walking up Nathan Road. We still didn’t know where we were going. It was strange to see the Chinese people just standing around the street watching us going past.

I suppose we were walking in a column of about 4 or 5 together. There weren’t any Japanese around. We were told then we were going to Shamshuipo where they had the barracks. One of the regular forces – either Middlesex or Royal Scots – and a whole lot of us walked about 3 miles from the ferry to Shamshuipo, into a building that had been completely pilfered and stripped bare of wood. (The Chinese people during the War couldn’t get fuel to cook.)

None of the buildings had any doors or windows and even part of the wooden roof had gone. The barracks were in long lines of about 50 yards, each with 2 doorways. In the front were 2 rooms where before the war the sergeant of the huts would stay. The men were in the common room which was a 30-40 yards long building with only one floor; outside of that were latrines, bath houses and showers.

Our company occupied one of the huts. Our uniform was all we had – jersey, a pair of socks and just the boots that we walked on, old shoes. We didn’t have any beds – we just slept in our ground sheets and two blankets that we had during the war, in lines on either side of the hut facing one another.

Around December, Christmastime, the weather was starting to get cold so we had to go around looking for sacks and sheets and try to cover the holes that were windows because the wind was coming in and it was getting pretty cold especially at night.

That’s how it was in Shamshuipo camp on Dec. 28th or 29th when we went in. That place was going to be our home from 1941 to August 1945.

Hundreds and hundreds of men came in through the camp gate. By that time there were a few Japanese soldiers at the gate making sure we all went in – checking on us and counting us. They didn’t know who we were nor we them.. We were separated from our company commanders who had a camp not very far from Kowloon Hospital at least 1½miles from us and we didn’t know much of what was happening. I suppose the Japanese feared a rebellion led by the officers. The only warrant officer with us was the sergeant of our company – the highest-ranking non-commissioned officer in the camp.

We found out afterwards there was a man called Major Boon who was brought in from one of the units; he was made our Senior Officer Commanding of Shamshuipo. He turned out to be a collaborator and at the end of the War he was convicted and sent to jail because of his collaboration with the Japanese.

Then Major Boon came in and all the sergeant majors of the different platoons had to give an inventory of all the men’s serial numbers, names and ages, etc. There were about 13,000 men were in Shamshuipo at that time.

It was then that we came to hear how the regular soldiers had fought the Japanese in Kowloon, though they were outnumbered and outmanoeuvred. The regulars had defended all the way from Lo Wu where the Japanese came across overland. With inadequate ammunition, men and guns our side had to withdraw back to Hong Kong.

ADJUSTING TO CAMP LIFE

During the first week we didn’t know what we were doing and just sat around, then organisation started with the Major calling the sergeants together. We had to clean up the place and make things comfortable. After 3 or 4 days it became reasonable to live in. There was a big main hall right in the centre of a big main road. Part of the camp was made into a hospital compound.

In Shamshuipo along the waterfront there was a big block of flats where in the old days the married officers or non-commissioned officers lived -a 3-storied building on one side and a big flat sandy area where we played a lot of sport later on.

Our camp soon became a small town with facilities which the Japanese allowed. It wasn’t luxury but it was a place where we could live. It would be wrong to say we didn’t have anything to eat.

In time food began coming into the camp and so we had rice, vegetables and sometimes fish. Things turned out better after a while when electricity was turned on and the place brightened a bit.

The 3 youngest boys – Luigi, Gerry and I – in our family were in camp, as were an uncle who lived with us, my sister’s husband and two or three cousins. Having our family family members together helped us through that difficult time.

The main topic of conversation was our loved ones at home. The married fellows would talk about their wives and children – sometimes they would throw a message attached to a rock over the fence. If the Japanese saw that they would be very angry.

Once a week our people were allowed to bring parcels but the Japanese never allowed the wives to come close to the barbed wire – they were kept about 100 yards away.

I remember once when the Japanese soldiers brought young children who saw their fathers with tears flowing, asking how they were getting on. My niece Maria who was only about 3 years old and her brother only 1 year old came right up to the fence, but we couldn’t touch her – only talk to her because we were behind the wire. They were shy but when they realised who we were they started talking freely. We couldn’t pass any messages because the Japanese were right there but it was nice to see the children.

At that stage in 1941 I was only 18 years old with no worries as I knew that my mother was well looked after by my 3 elder brothers – at that stage only one of them was married. Linda, the oldest girl in our family, was married already. My brother-in law Reinaldo was also in the prison camp with us. The fact that my other brothers were also in the camp helped ease the hard part of separation. We took each day as it came.

We were allowed to write and receive letters and learnt that Mother and family were leaving Hong Kong to go to Macau which opened its doors to the refugees from Hong Kong. We had to sell our family home in Soares Avenue when the family left.

I said prayers but wasn’t especially devout. Most of us Portuguese fellows attended mass and prayed every day. We had a chaplain who volunteered to come into the camp to administer to the boys who were Roman Catholics. He said mass every day in one of the little huts that was allotted to him as a chapel. We had another priest – Father Green – living in the camp who was later decorated by the Queen for his wonderful service to the prison camp in Hong Kong Shamshuipo. Naturally we turned to God because of our faith – we believed God would help us and reunite us with our families. The only way we could be with the ones we loved was through prayer – at that stage I didn’t know much about it either but we had faith God was with us and would help us.

Some of the men smoked – they could get cigarettes from the canteen – but we could only get edibles in the cookhouse. Things people took a fancy to started to arrive in camp, but you had to pay for them. Money was given out by the pay department of the Volunteer Defence Corps.

Being only 18 with grown up men who knew a lot about life and talked a lot, I quickly learnt the facts of life. We didn’t get up to much mischief in the camp.

We made very good friends and these friendships developed in the camp for the four years from 1941 45. Many different nationalities were there – Eurasians, Indians and others, and we came to know most quite well.

Camp life passed very quickly because we had to work – we used to go about 10 in the morning and return at 4 p.m. Five or six trucks would come in and we would pile about 40 to a truck. We had to move drums from one part of town to another. Those on working parties would have a whole day out of camp and see their family and friends. Their wives and children would be around that area and wave to them.

THE COOKHOUSE

We had to build 5 kitchens in different parts of Shamshuipo because all the utensils had been taken away. The ordinance corps built the stoves and volunteer cooks were called for. The engineers got bricks from outside to make stoves and put in big kerosene drums which they used for cooking rice. They had huge woks – 10 sizes bigger than those for domestic use – that were used to cook vegetables and fry the fish. Most of the food was made into soup. There wasn’t much food, but we were kept alive.

After a time I was called by the platoon sergeant to work in the cookhouse and was separated from my brothers and the company. There were six of our fellows cooking rice because that was our staple food. Occasionally there would be fish. It was a great sight at the beginning of camp days when we saw the Japanese bringing in about 15 live pigs, because we knew we were going to get some pork.

Two pigs were given to each cook house and we had to kill them ourselves. We didn’t have knives – only pen knives. You can imagine the commotion with two men trying to hold down the pig, the pig squealing and the men swearing, and finally all the noise subsiding when the men killed it. There was a drum outside full of water; a couple of fellows stoked a fire to heat the water so that they could submerge the pig and scrape off all its hair. We didn’t have much food so even the intestines of the pig were eaten. All we could do was boil the pig and put some salt on it. It went quite well with rice but we couldn’t eat too much of the fat because it made us sick.

We had six rice cooks who had their own stove, chopped the wood and looked for fuel for the fire. We had breakfast and one other meal at about 5 in the evening.

There were thousands of pieces of fish which took all night to cook in a big wok with fat from goats that the Indians sent to us; the whole place stank.

We didn’t have many encounters with the Japanese guards, and only had one or two skirmishes with them. I remember one night when I was on duty with another cook, when in walked 2 guards with their fixed bayonets and tin hats demanding to see what was going on because the light was on. They commanded us to put the lights out. We had to respect them because it was nothing for them to shove people with their bayonet. One of the guards started to eat our food so we told them to get out; they sheepishly took their guns and walked out of the cookhouse.

Being in the cookhouse I was never without any food. Others had parcels sent in by their families but after some time these stopped because the Japanese sent all our Portuguese people to Macau.

MUSICAL INTERLUDES

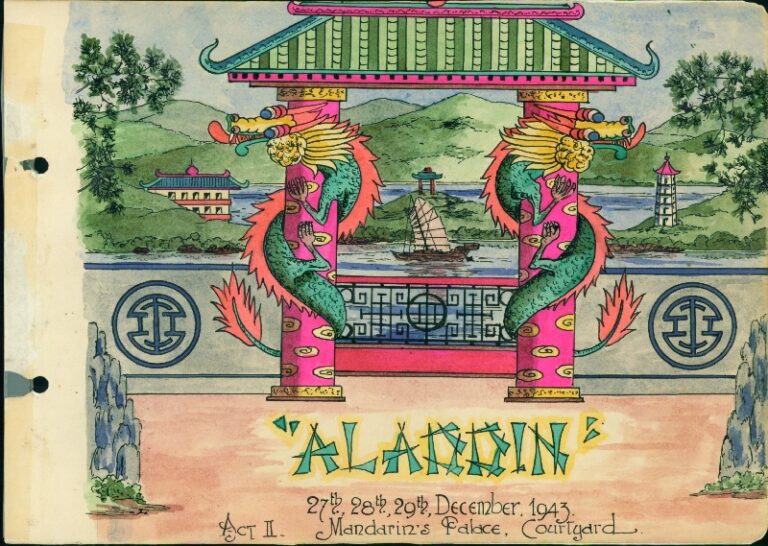

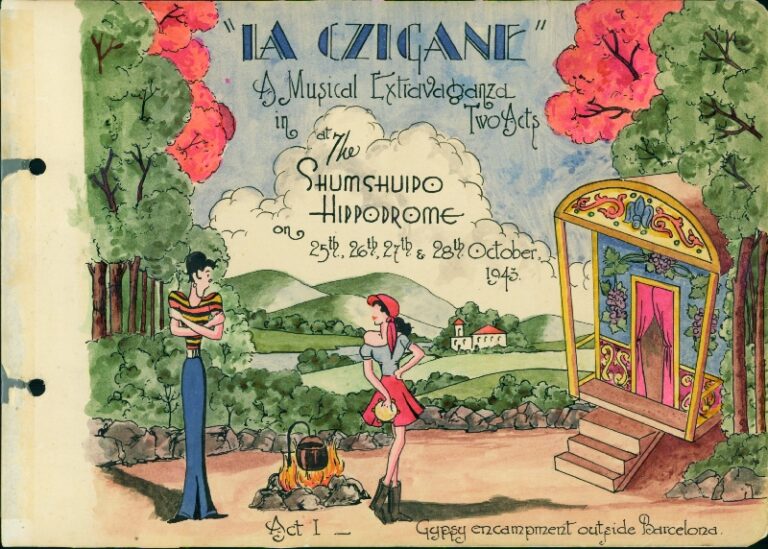

The Japanese brought musical instruments from the different barracks in Hong Kong and Kowloon and the bandsmen from the Royal Scots, the Middlesex Regiment, and the Canadians started rehearsing to provide music for the men. There were about 250-300 men playing in camp orchestras.

The Japanese also brought a lot of books and we formed our own library. It made up a major part of our recreation because we read a lot in camp, both for study and leisure.

The Canadians had a beautiful swing band with a fellow who played the clarinet very much like Benny Goodman, a Dixieland jazz band and a symphony orchestra, with about 150 players and we had entertainment from then onwards. The bands practised in the hall and you could hear music every day.

Every Sunday we had a concert – men sat around on stools listening to beautiful classical pieces. One of the spectacular moments of our camp orchestra was when the bugler went up to the roof and played `William Tell’ on the trumpet. There were about 130 of us sitting around and the grounds were full of prisoners lounging around, relaxing and listening to this beautiful first-class orchestra. They not only played Sunday afternoon but on Saturday also.

Every month we would have a particular group giving a concert or a musical or a play to entertain the troops. The Japanese clapped and thought it was good – they came in armed with bayonets, rifles and swords. There were so many men in the camp and only one hall so these plays were done 3 times each evening and different tickets were allotted to different groups. It was really wonderful that we had all these live shows to relieve the minds of these prisoners of war.

We didn’t have much to wear – we had our shirts, cardigans and jumpers; in summer everyone stripped to short pants. Once we saw some women walking down the street and we felt indecently dressed in front of them but we found out they were Canadian soldiers, female impersonators, who must have got dresses from somewhere – they looked pretty flash.

Life was quite easy but the British people were put in Stanley in an internment camp and I believe they went through far worse than we did.

HEALTH

There were long queues for everything. On sick parade in the morning you had to queue up to see a doctor. In the beginning not many of us needed the doctor but later a lot of the boys were getting beriberi (the result of a lack of vitamin B). The Senior Officer Commanding spoke to the Japanese about bringing in flour and yeast and the engineers started building a bake house with ovens. We developed yeast in a bath in the bake house and had 3 professional bakers to bake bread. We needed a mighty amount to feed 13 14,000 men and we were only issued a little piece of bread each day.

There were epidemics of cholera, dysentery and throat infections that killed many of our colleagues. The last post would be blown by our bugler to let us know that another prisoner of war passed away and we would stop for a minute’s silence. There were times when a truck would come in and pick up about 15 or 16 bodies to be buried outside of the camp.

Many people were mentally disturbed from being deprived of freedom and separated from their loved ones.

There was another type of disease that was also very painful and felt as if needles were being stuck into the soles of the feet the soles. The doctors could never diagnose it but ‘electric feet’ was the name we gave it in camp. You could see these poor fellows walking around with sticks – it hurt them to take steps – and you could see the pain in their faces. They grew very thin, weak and wan-looking. Their eyes were downcast and there was no sparkle in their face at all – and they went through this for 2 to 3 years.

One of the camp doctors was the captain of our cricket team, Dr. Albert Rodrigues, now Sir Albert Rodrigues (he was later knighted by the Queen for his services during the War).

ESCAPES

Every day we had tenko (roll-call) when all the prisoners had to be out in the parade ground. The band used to play, we would march onto our lines, and the Commander and a few of his corporals would count us. It took about half an hour because there were so many men.

After a couple of years prisoners began to think of escaping. As I explained, Shamshuipo was quite near the harbour – the married quarters were just by the harbour. We were behind big barbed wire fences but there were manholes to tunnels which led into the harbour. I remember the first escape by 3 English prisoners of war. One was a lieutenant in the navy – I think his name was Elliot, and he wrote an article after the war about his escape from Shamshuipo. It was very interesting because they went through a tunnel into the harbour, swam to Laichikok, got in with the underground Chinese Army, escaped to Chungking and from there went back to Britain.

On the evening count they found out that three were missing so they kept us in the open all night and all day in heavy monsoon rains – we were sitting out there for nearly 12 hours. They searched the camp inch by inch but did not discover how these fellows had escaped. The Japanese got very angry. They took 25 prisoners out into the yard and put four machine guns around them and said they were going to kill these fellows unless someone told how these three fellows got away. We didn’t know – maybe their friends did. These 25 were kept out in the open for about 5 days with no food. We were warned that if anyone escaped again they would kill others as a reprisal.

Every day we had tenko (roll-call) when all the prisoners had to be out in the parade ground. The band used to play, we would march onto our lines, and the Commander and a few of his corporals would count us. It took about half an hour because there were so many men.

After a couple of years prisoners began to think of escaping. As I explained, Shamshuipo was quite near the harbour – the married quarters were just by the harbour. We were behind big barbed wire fences but there were manholes to tunnels which led into the harbour. I remember the first escape by 3 English prisoners of war. One was a lieutenant in the navy – I think his name was Elliot, and he wrote an article after the war about his escape from Shamshuipo. It was very interesting because they went through a tunnel into the harbour, swam to Laichikok, got in with the underground Chinese Army, escaped to Chungking and from there went back to Britain.

On the evening count they found out that three were missing so they kept us in the open all night and all day in heavy monsoon rains – we were sitting out there for nearly 12 hours. They searched the camp inch by inch but did not discover how these fellows had escaped. The Japanese got very angry. They took 25 prisoners out into the yard and put four machine guns around them and said they were going to kill these fellows unless someone told how these three fellows got away. We didn’t know – maybe their friends did. These 25 were kept out in the open for about 5 days with no food. We were warned that if anyone escaped again they would kill others as a reprisal.

DRAFTED TO WORK IN JAPAN

Periodically the Japanese would draft a group of prisoners to work in Japan. We learnt after the War that the Geneva Convention allowed the victor to use the other ranks as workers even in their own country and this is what they did with us from about 1942.

The first draft took about 1000 men. They picked the fit ones and left the old, the decrepit and the sick. They marched out of the camp accompanied by a band. Trucks took them to the ship and off they went to Japan.

After the first draft it would occur more frequently, taking groups of 500 and then 700 men. One of these ships carrying Hong Kong POWS was the Lisbon Maru, which was torpedoed by an American submarine. A number of men lost their lives and survivors were picked up by Japanese gunboats following the ships. A few of the fellows after the war talked about it. In fact, a survivor, Harry Winsborough, lives in Dunedin today.

We did all sorts of things in the camp to entertain ourselves and I remember a man in camp called Charlie Dragon who had been a teacher at St. Joseph’s College. He was one of the best mathematicians who ever taught at St. Joseph’s and was quite a character. He was going around trying to amuse the fellows by reading palms to tell the future. He came to the cookhouse and looked at my palm and said “You know, Zinho, you will be around for a long time” and I replied that I hoped so. Then he said, “You are going to go on long trips – you will be going to places where you are not meant to go, where you didn’t want to go but you will have to go.” We all knew it meant a trip to Japan so we all laughed because they didn’t send cooks away on draft. I didn’t think much about it.

The first trip came not very long afterwards because I was also caught in the draft. How it happened was that the cooks were getting sick of being confined to the camp. We had been working for nearly 3 years every day with no holidays so some asked to be allowed to go on working parties just to have something different to do and to go out in the fresh air and suns.

Boss Busty Bowers, the chief of the cookhouse, agreed and allowed two of his cooks to go every day. So we used to go out once a fortnight in working parties to build roads up Tai Tung Gap, build an aerodrome, fill up holes, dig mountainsides, etc.

One day I was put in a working party of about 250 with my cousin Manuel Marques and three others from the cookhouse. We went by junk to a place in Pokfulam and worked all day. When we returned to the camp we were all taken to a a corner of Shamshuipo camp and surrounded by guards. Barbed wire was put around us and the Senior Officer Commanding said, “This is the draft that will be sent to Japan in 2 days.” I only had time to call out to the fellows in my room to ask them to bring some of my belongings.

This had never happened before. People sent to Japan in drafts had always been picked by the Commandant -normally English or Scots fellows, mostly the regular forces – but we were just picked out of the blue. There were 250 of us of different nationalities including 60 or so Portuguese boys. It was also unusual that they didn’t give us much time.

The doctor came and passed us as being fit and gave us a few injections for the travel. We were given extra clothes for our kitbag and within two days we were on board a ship going to Japan. I left behind my two brothers Luigi and Gerry, my brother in law and a few cousins but one of my cousins came with me. We were put in the hold, sleeping in tiers. The hold was covered so we couldn’t see a thing on the voyage. We ate Japanese preserved vegetables and rice. I remembered this must be the first of the unseen journeys I was going to take that were beyond my ability to say yes or no.

We were on board that ship for 5 or 6 days. We went first to the top of Taiwan, then to Shimonoseki, the southernmost sea port of Japan in the island of Honshu. They took 3 trainloads of us POWs with our kitbags through the outskirts of Hiroshima to the outside edge of Tokyo. From there we went to Sendai about 150 miles north of Tokyo.

It was quite a memorable journey. We stopped at various stations and the Japanese fed us with bento boxes (rice and barley, preserved soya beans that gave a little bit of flavour to the rice); they also gave us soup and hot water.

It was April 1944 that we arrived in Japan, which at that stage was going into summer. It was beautiful, with mountains similar to New Zealand. In spite of the cramped conditions we enjoyed the trip. We said we would never have come to Japan unless the Japanese paid for us; we were guests of Emperor Hirohito. You had to make a joke of things otherwise you would go under.

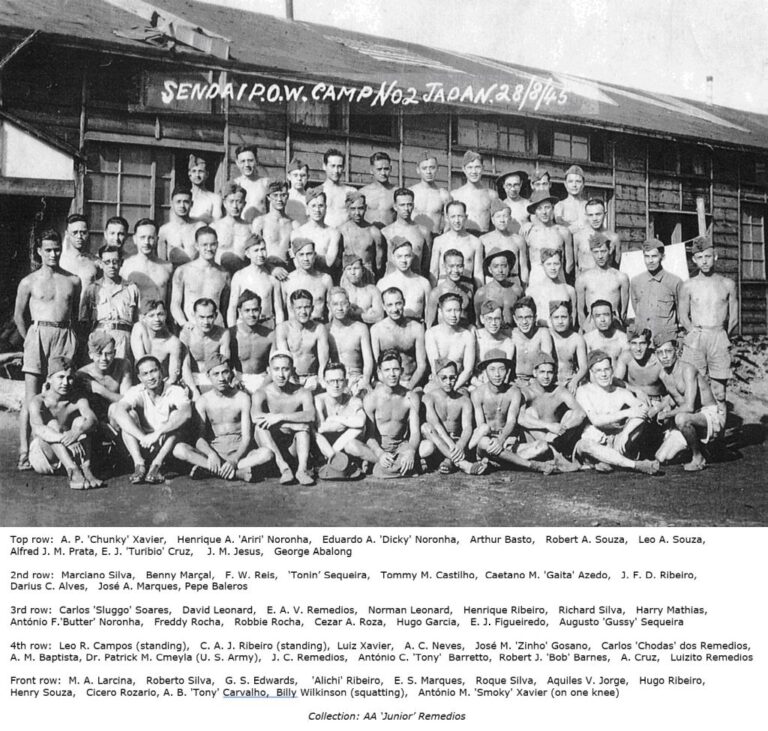

It was getting dark as we got out of the train into trucks with our kitbags and travelled about 3 miles to our camp where we remained from April 1944 and till the day of liberation in 1945.

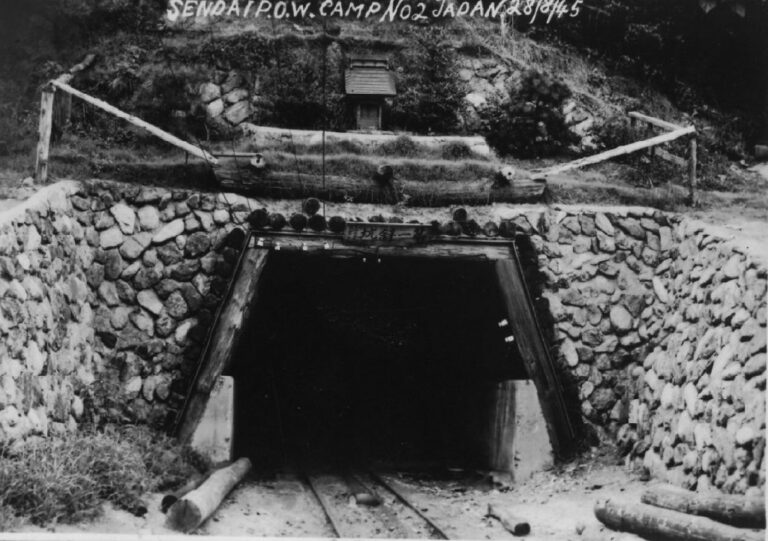

SENDAI NO. 2 CAMP

We didn’t know what was in store for us when we walked into this high walled camp. On the left were two big huts bordering a little playground which was about 30 yards by 20 yards. There were buildings at the far end and a few other buildings around this little square. 125 men were put in each one hut. All the Portuguese boys came together in one hut. We were each given a number – mine was 159.

The Japanese prison camp in Japan was very different to that in Hong Kong: in Japan we only had a little compound with high walls – but it would be no use trying to escape in the heart of Japan.

There were two huts separated by at least 5 yards of open space. They were simple wooden structures with glass windows that might have been constructed in five days. Each hut was small – no larger than two oversized chicken runs with a 6-foot wide passageway in the middle. At one end there was an entrance, with an office on one side and doctor’s office and sickbay on the other. There were two levels of sleeping space which were covered by bamboo tatami mats, where we slept, with one blanket under and two over us. We had to take our socks off to walk on the tatami.

There were 2 or 3 little stoves which were lit in winter. Those sleeping on the top level got the most benefit from the warmth of the stoves. There were shelves on the walls where we could put our clothes and personal items. At the other end of the hut there was a toilet block with 10 taps. Beyond the taps were small cubicles with toilets which were just holes in the ground. You had to be careful not to fall in because there was a big pit underneath that collected all the waste.

The Japanese were quite good. They gave us some warm clothes because they knew the winter was going to be cold and coming from Hong Kong we’d really feel very cold. I remember we had snow outside about 3 feet deep that first winter there.

We were told the next day we were going to work in a coal mine. We were all former white collar workers in Hong Kong and had never lifted a shovel in our lives. Physical work needs muscles so we were fortunate the Japanese gave us 2 meals a day.

They gave us a couple of days to get acclimatised to the conditions and then an English-speaking Japanese came and told us what we were going to do and how we were going to do it. In every group there was a driller and 4 shovellers led by a foreman (an experienced Japanese miner) who had to teach us how to bring down the coal. Our quota was 20 tons a day (20 full trucks) – quite a lot of coal.

One hut did the day shift and the other hut the night shift. We worked for 11 or 12 days nonstop if we were on a day shift, then changed over to the night shift and had a day off. Every 12 or 13 days we had a day off. That was the only time we had to talk to one another and reminisce about the old days. Being in a hut where most of us were Portuguese, we would say prayers. God help you if you didn’t pray while working – psychologically it was very important to ask God for help and be with us and look after us.

THE COAL MINE

We were given a Japanese uniform to which we had to sew our number on the left pocket. We only wore it when walking from the entrance of the camp to the coalmine.

The coalmine was half way up a hill. From there we went down 1,200 feet by cable car to the coalface. We wore our clothes on the way down the main shaft where air was pumped through but as soon as we left the main shaft it would get very hot and all we wore was a fundoshi (which is like a g-string) and Japanese gym shoes which had splits for the big toes. On the way up four or five cars were pulled up at a time.

Being the youngest and fittest I became the drill man, responsible for bringing as much down as possible. We drillers had to learn Japanese; every day words were put up on the board and phonetically spelt out for us. I learnt quickly, knew a bit more than the other fellows there.

Not many could lift the drill, which weighed about 60 lb and shook like mad. You got used to it after a while – the monotony of the job and the tiredness. It was dirty work but you had a Japanese bath afterwards. They cut our hair off otherwise it would have been too filthy.

I had four shovellers with me. One of them was my cousin Manuel Marques – he’s in Hong Kong at the present moment; another one was Satiro Sousa – he’s away in Los Angeles. And another was Henry Ribeiro; he’s dead now. All in all we were very fortunate in surviving the War. Of course it’s 45 years ago now.

We were lucky to have a good boss. He shared some of his food with me sometimes because he knew I was the one to get the coal out. He was an expert at drilling coal and would at times dig out a couple of truckloads himself so that I could have a rest. We actually developed a very good relationship.

After a while you get the knack of drilling coal. There were 4 layers of coal of which the two middle layers were very soft and the top and the bottom layers were very hard. The boss and I would drill the top and bottom with a chisel drill, put dynamite in the hole and blow up the face. I did all that while the shovellers sat on the outside and had a bit of a rest. We would then make sure the roof wouldn’t come down. The shovellers would take half an hour to clean up what had brought down with dynamite.

We dynamited once a shift. Depending on the height of the shaft, we would probably go in 6 feet deep to extract the 20 tons of coal that we brought up every day. Our forced labour helped the Japanese war effort but we had no choice but to do it.

And this was where I again experienced God’s finger in my life: I had another very close call when I was drilling in the face of the coal alone. When I drilled I used to send the fellows away from the drill face – I didn’t like them to stand around. I was strong enough to pull chunks of coal from the face of the shaft and I must have drilled nearly 2 tons of coal – a big heap. Then I thought I’d go back and have a rest and some fresh air. So I put my drill down and walked back 2 steps. I heard a crack and knew the roof of the shaft was coming back so I ran like mad and was out of the shaft like a rabbit. Then I heard this tremendous fall of rocks caving in. Where I had been standing two seconds before there was a heap of rubble about 3 5 feet high and I could have been under that – that was my second escape, the second time the Lord spared me.

Life was relatively easy. We had some thrills when we saw an American spotter plane flying over; we would cheer like mad and the Japs would fire a few shots up in the air to get us off the road. We would tease them and call them all sorts of things but they didn’t know what we were talking about.

The days in Japan went very quickly. We realised the Americans were getting near to Japan when the Americans bombed Sendai. This was when we were down in the coalmine on night shift. When we came up the fellows who were there said: “Oh boy, you want to see it – tracer bullets flying everywhere. We could see everything happening in the city of Sendai”.

We had 2 or 3 fellows cleaning up the Japanese Camp Commandant’s office and they used to come out with the newspaper. Some of the fellows, who could read Chinese, deciphered the Japanese language and so they knew all the islands were slowly being taken by the Americans.

On the 15th of August we went down on night shift. The fellows who were coming up from the day shift said “Hey we did only about 12 trucks.” The other fellows said “We only did 8”. They said the bosses were sitting around talking and smoking and not doing anything at all, so we said we’re not going to do anything either.

We just sat around the coalface and the 3 or 4 bosses of them just sat around smoking and talking and the rest of us just sat around. Some of us put little planks along and lay down and went to sleep. Our night shift did only 7 trucks.

When we came up we had our shower and were having our breakfast when some of the fellows went past our hut and asked, “Hey what’s happening down there?” We said we didn’t do much work either. There was a rumour that the Commandant was going to talk to us after breakfast. Suddenly we heard a terrific howl and cheers and the fellows came running in and said, “Hey, the war is over, the war is over!”

That was the 16th of August – the war was over on the 15th and we got the news the day after. We were halfway through our meal. We looked at one another and lost our appetite and started to talk about what was going to happen and when we were going to see our people again.

I remember sitting down on my bed on the top row, looking down at these fellows mooching about another and I thought to myself, “If I could only do something for people like that”. I never thought I’d be a priest even at that stage but I wanted to do something.

How true it was! On the 1st of September we had word from Tokyo that B29’s were coming over to drop food supplies over Sendai so our Senior Officer Commanding (a Canadian) said, ” O.K. men, I want you all out of the here and about two to three hundred yards away from the camp because we don’t want any of you being killed – not when everything is over. Only a few more days and we’ll be liberated from Sendai.”

The time came when I had my third narrow escape. It was the 2nd of September, and the planes were coming over.

I happened to be cook on duty. I was up at about 5 a.m. to start the fire and cook the rice and vegetables for the men’s breakfast when the first plane came over. I stood at the door of the cookhouse watching it come past. It looked really beautiful with its bomb bay open, and out came what looked like a stretcher with 2 parachutes on it, and a whole lot of kit bags full of food – breakfast, dinner and lunch K-rations – they dropped hundreds of these kit bags.

I saw a second plane approaching, and then I saw a fellow called Sai Serata an American technical sergeant and radio expert, who was up there on the roof. He was pulling away at the connection between himself and a little makeshift Signal lamp, signalling to the plane as it came over.

I went up a ladder, and stood by him to give him a hand. He was signalling to the second plane as the first B29 came over flying about 400 500 yards high, coming at speed – I saw the bomb bay open and a stretcher came down and all the kit bags. The stretcher came much faster than the kit bags. I could see this 4 x 4 stretcher coming down like a cartwheel and said, “Look out Sai, its coming to us.” I turned around to run but this thing just hit me on the ankle and also hit Sai. He never knew what happened because it must have broken every bone in his body and he went straight through the roof.

I fell down on my hands – my left foot was still on the roof but I couldn’t see my right foot. There wasn’t any pain but when I looked there it was behind me right up in the air. The tibia – the thicker bone in my leg – was sticking right through my ankle and the whole foot was by my knee. I was stuck there – I couldn’t move.

Two of the ex-prisoners, David Leonard and Jo Bone, who knew me quite well (we used to play softball and baseball together), strong fellows, both over six feet tall, ran into camp and up the ladder. They carried me down and took me to the sick bay. The doctor gave me a couple of morphine injections: one above my knee and one further down. He said: “You’d better hang onto the stretcher.” The doctor took the bone from my knee and pulled it back towards the joint and put my foot right back into the tibia and at that stage I felt a little bit of pain. He cleaned it up with gauze, put some penicillin around it and he strapped it up with plaster and bandages.

So that was the third time that I escaped death. The fellow next to me was killed and I thought, I could have easily been killed myself. I still never thought of becoming a priest.

CONVALESCENCE

I was taken from Japan on the hospital ship Tjitjalengka to Auckland, New Zealand where I was hospitalised for about six months and treated very well. Then I was taken to Rotorua, to a very beautiful hospital for orthopaedic cases – those with broken or severed limbs. My foot was starting to heal but there was a big gaping wound on my right ankle.

The British Government said there was no room in England for former prisoners of war so we were taken to New Zealand and left there until England was able to accept responsibility for us. I was quite happy in New Zealand; the people were kind and generous.

In Rotorua I was starting to walk but my ankle had Ankylosis – some matter got in between my foot and tibia so it became stiff. They tried to work my foot with mineral water, exercise and therapies every day. I also did a lot of exercise, playing golf, going swimming, doing all sorts of things to get the foot working but it didn’t happen.

This returned servicemen’s orthopaedic hospital was very near to a church and I used to go every Sunday – never missed it and joined the choir. There was a lady who could play the organ and was very kind and one day she asked me over to her house for tea. She was living with her mother. When the mother went out of the room she said, “Look, José, have you ever thought of becoming a priest?” I politely contradicted her: “Become a priest, no, I’m not the type; I love life and every Saturday I used to go to the local dance hall.” That was the first time anybody asked me about be-coming a priest.

In August 1946 the Medical Superintendent said, “I’m sorry, José, we can’t do any more for you now. Would you like to go back to Hong Kong or England where you can be demobbed?” My brother Eddie had just gone to London to study for his doctorate in surgery, so I said, “Oh, I’ve got my brother in England, so would you give me a ticket to England?”

They signed me up and away I went and stayed for six months with Eddie and his wife who had just given birth to their first baby. Being the only member of the family in England I became godfather of the baby. My brother went to Edinburgh to study while I looked after his wife and beautiful little baby.

A few ex-prisoners of war had settled in Britain and we went around together. After six months I decided to get out of the army and return to Hong Kong. Hockey, tennis, baseball and softball were out of the question but I got quite keen on playing cricket and instead of being a bowler and a batsman I was wicket keeping for the Club.

One day I met a man called Sleet in the street whom I knew in the prison camp. Because he was old and by himself, I used to chat with him and give him extra food from the cookhouse. He was now a manager of the Hong Kong Jockey Club and he invited me over to his office to have a chat about my future.

So I went with this very nice old man. He asked whether I wanted a job and I said I wasn’t dying to work yet. He offered me an accounting job in the firm. I went home and discussed it with my mother and brothers who said, “Why don’t you go and do it?”

So I decided to take the job and worked for about six months but finally thought to myself, “I don’t think I could go on living like this.” The work didn’t appeal. I had that idea in the prison camp of doing more than just working as an ordinary clerk or book keeper. I discussed with my mother and said, “Look, Mother, I’d like to study – I haven’t studied since 1936,” and proposed returning to La Salle College to study for one year and see if I could pass my matriculation.

My mother queried what I would study for and I suggested that, as Eddie was a doctor, maybe I would study to become a dentist. When Lino, the oldest brother, came home, I asked him about it and he said, “Zinho, if you want to study, you go and study. Your brothers have good jobs so you don’t have to worry about money. We’ll support you all the way, financially.” I said I should have enough money from all those years in the prison camp. So I went back to Mr Sleet and thanked him very much for what he had done and said I was going to study and become a dentist.

I didn’t tell him my ulterior motive – that I wanted to help people. I returned to La Salle College where I had previously been studying. This was the first time I’d ever swotted. Before the war I did all my homework but I’d never swotted as hard as I did then.

This was when I started going to mass daily. We lived only 150 yards from St. Theresa’s Church on Boundary Street. When I received the Lord I used to say to Him, “I promised you I wanted to do something for you and I said my whole life would be dedicated for you and for people. I had already identified God with people, our Lord himself was in them. So the Lord took me up. I studied very hard and every day when I received communion, I said, “Lord you show me the way – if I pass my exams then that’s it, I know you want me to do something.”

The time came and I gained matriculation. So I said, “Right, I’m going away to study to become a dentist.” I had met some very good people while I was in New Zealand and they got me a place at Otago University. But in the meantime, I used to go to the Club and have an orange juice or lemonade and listen to Father Lima who was a Maryknoll missionary down at the St. Stephen’s College in Stanley.

Father Lima knew the Gosano family very well. He used to come to our house – stayed with us, had lunch and dinner and was very friendly with all the brothers who played sports with him. While I was at the Club watching them play tennis he came and sat beside me and said, “Look Zinho, in the Portuguese community in Hong Kong, you’ve had Portuguese girls who’ve become nuns and the boys brothers, but the Portuguese community has never had a priest – now, what about it?” I said I’d never thought about becoming a priest – I love dancing, I love life, I enjoy girls’ company, apart from that I can’t imagine myself becoming a priest. But I have thoughts of becoming a dentist. That’s one way I can serve humanity and do something for people in general.

That evening he came and had dinner at home. We were gathered together around the table. Father put on his collar, threw away his cigar and prepared to return to Stanley. We said goodnight to him and he turned to Mother and said, “You pray for this fellow Zinho – maybe he will have some calling from God” and Mother said, “Oh, he is going to New Zealand to become a dentist.” Father Lima said, “You never know – keep up the prayers for him.” At that stage I was the only single one, all the other brothers already had girlfriends and wives.

FROM DENTAL SCHOOL TO PRIESTHOOD

I went to Hong Kong University and did some pre dental work there and played cricket for the University and also for Hong Kong. Sport was not my main focus – I was more concerned with following the life of a dentist. At that stage I was prepared to go to the first place that would accept my application. Hong Kong University did not then have a Dental Faculty. I wrote to my brother in law in Sheffield because there was a very good dental school there and to New Zealand but could have gone to America or Australia.

God gave me a sign all right. I knew some very nice Jewish people in Dunedin, Mr & Mrs Ellis and two sons. When they heard I wanted to follow dentistry they must have put in a good word for me to the University of Otago. I was told I could go to any university in New Zealand to study for my pre dental. So I went to Dunedin, joining in the social life and studying very hard to try to pass my pre dental exam.

I did one year at Canterbury College in Christchurch and then went to the dental school at Dunedin where I met this girl and became very friendly with her. We used to go to mass every day together. She came from a very nice Catholic family that I came to know quite well. Her brother was studying to become a Deacon in the Columban Mission.

One day I took her to the pictures and then to a café. She asked me over coffee, “José, have you ever thought of becoming a priest?” You can imagine what I felt. I really liked this girl, and had even written to my mother to say how nice she was and that if ever I bring a girl home it would probably be one like her, and here she is asking me this.

That night, after taking her home and returning to my boarding house, I couldn’t sleep and the next morning I was thinking how God had spared me three times. Now to have three people – the lady in Rotorua, Father Lima in Hong Kong and this girl in Dunedin – put the same question to me, I thought, “Maybe, my gosh, maybe these are people from God who have come to me in different ways to ask me to try to become a priest.”

ORDINATION

First thing in the morning I phoned a priest – a curate at the Cathedral in Dunedin whom I had met – and said, “Look, could you come up to me please? I just want to ask a few questions.” Within 5 minutes he was there. We had a chat and I told him that I had an idea of becoming a priest and asked what can I do. He went to the Bishop and said, “We’ve got a young fellow here from Hong Kong who would like to become a priest.” The Bishop said, “OK, if he wants to become a priest ask him to go to St. Kevin’s College in Omaru.” This is a town where they were teaching returned servicemen from overseas to become priests.

I went to St. Kevin’s and did a whole scholastic year of Latin and Greek but also played cricket and other sports – it was great fun. Learning Latin was also fun but I’d never knuckled down to study as I did from then onwards. I knew the Lord had something for me to do. I wrote to my mother and told her I’d changed my mind about becoming a dentist and said I was going to try to become a priest. Mother wrote back to me and said she was overjoyed. She told me something she had never mentioned to any of the boys or girls in the house: that since my father died when I was only 3½ months old she had been praying that God would take one of her children for his own, that they would be completely and wholly devoted to the life of God. Now I was the only one left, and I was the one picked out.

It’s alright to say you want to become a priest, but many have started but never finished. I had to do one year of Latin and Greek and then seven years in a seminary at Holy Cross College in Mosgielt. It was hard work, to learn all the theology, philosophy and Canon law – everything in Latin. But everything is possible with God on our side. There I laid the foundation of my priesthood and have never ever been sorry and am still going 34 years later.

I was ordained in 1957 in Hong Kong at St. Theresa’s Church where I had been altar boy. Later, just after returning from prison camp and from England, I joined the choir and sang Panis Angelicus and surprised the congregation who did not know who this fellow was.

A VIDA E OS TEMPOS DO PADRE JOSÉ “ZINHO” GOSANO

Primeira publicação no Boletim da UMA Abr-Jun 2011 Vol 34 No 2

[Nota do Editor: Há alguns anos, o amigo do falecido Padre Zinho Gosano na Nova Zelândia, o Padre John Griffin, enviou ao editor do Boletim de Notícias da UMA um disquete contendo uma narrativa autobiográfica do Padre Gosano. Foi originalmente feito para o Padre Hayes, que publicaria um artigo em uma revista militar após a reunião dos 50.º prisioneiros de guerra em Hong Kong, em 1991. Recentemente redescoberta, a história da vida e da época do Padre Gosano é uma leitura interessante, particularmente para aqueles da diáspora macaense que foram criados em Hong Kong em meados do século passado e para quem as experiências da Segunda Guerra Mundial deixaram uma marca indelével. Também tem significado para as gerações mais jovens, cuja própria apreciação do que seus pais e avós sofreram durante aqueles anos pode ser ampliada pela história pessoal de um jovem.

Esta edição começa com a infância do Padre Zinho e a família à qual era profundamente devotado, suas façanhas como desportista habilidoso em Hong Kong antes da Segunda Guerra Mundial, seu serviço na defesa de Hong Kong na época do ataque japonês em 1941, sua subsequente internação como prisioneiro de guerra no campo de Shamshuipo, em Hong Kong, e o tempo que passou, ao lado de outros prisioneiros de guerra, realizando trabalhos forçados em uma mina de carvão em Sendai, Japão. Seu relato continua com as consequências da Guerra e sua reabilitação dos ferimentos em um hospital da Nova Zelândia, uma estadia no Reino Unido e sua decisão de ingressar no sacerdócio como resultado direto de seus três encontros próximos com a morte durante a Guerra.

Sua história é apresentada aqui da mesma forma como ele a narrou, com alterações ou algumas inconsistências na sintaxe, nomes próprios, pontuação e reorganização em ordem lógica.]

MINHA FAMÍLIA

Os Gosanos eram uma família portuguesa muito conhecida. A mãe era de ascendência portuguesa. Os pais, chamados Marques, vieram de Macau e se estabeleceram em Hong Kong.

aposentado como major das Forças Armadas Portuguesas. foi batizado e cresceu em Macau, vindo para Hong Kong em busca de emprego. Lá, ele conheceu minha e eles se casaram na Catedral, então a maioria de nós nasceu na Ilha de Hong Kong, não muito longe de Happy Valley. Há uma igreja lá chamada Igreja de São Francisco, onde todos fomos batizados.

A pequena comunidade portuguesa em Hong Kong passou a se conhecer muito bem. Tínhamos um clube – o Clube de Recreio – onde praticávamos nossos esportes.

Crescemos como uma família muito unida e unida. Éramos 9 pessoas na família, 7 meninos e 2 meninas – eu era a mais nova. Em casa, tínhamos 2 ou 3 empregados chineses, então cresci com cantonês e português na família; o inglês era bem simples, então eu tinha 3 idiomas.

Meu pai morreu quando eu tinha 3 meses e meio, afogado acidentalmente no mar. Meu irmão mais velho, A.V. (ou como era conhecido por todos em Hong Kong) cuidou de mim.

Tínhamos uma vida familiar maravilhosa – além de nós nove mais a mamãe, tínhamos dois irmãos dela morando conosco. Mamãe também cuidava de outros quatro órfãos – filhos do irmão dela (um menino e três meninas), e depois outra família da minha mãe também costumava ficar conosco, incluindo dois meninos. Então, tínhamos uma família incrível, com cerca de 18 ou 19 anos. Foi nessa vida familiar que fui criado, cheio de amor e união, todos cuidando uns dos outros. Acho que, por ser o caçula, eu era um pouco mimado – meus irmãos eram muito bons para mim.

Por volta de 1932, fomos para Homantin e compramos uma casa de dois andares lá. Ainda tínhamos alguns membros da família conosco. Além da mamãe e de nós, nove filhos, nossos primos Roberto e Vancy e meu tio Afino estavam lá, embora os outros primos, as três meninas e um menino, já tivessem nos deixado. Éramos cerca de 15 ou 16 na casa e foi muito divertido. O novo bairro era bom e não lotado. Morávamos na Avenida Soares, em Homantin, onde havia alguns portugueses que haviam comprado as casas ao nosso redor. Duas famílias portuguesas que moravam lá se chamavam Gutierrez e Yvanovich. Tínhamos uma grande multidão de jovens que se divertiam muito juntos.

Naquela época, ainda estávamos na escola, mas alguns de nós que já tínhamos saído ainda nos reuníamos com essa multidão. A Igreja de Santa Teresa ficava a apenas um quilômetro de distância; As meninas frequentavam o Convento Maryknoll, onde as Irmãs Maryknoll americanas ensinavam, e nós, os meninos, tínhamos o Colégio La Salle a cerca de um quilômetro de distância. Crescendo em uma sociedade muito agradável, passávamos muito tempo juntos.

O trabalho escolar não era difícil, pois eu sempre era muito atento às aulas – aprendendo tudo na escola e fazendo os deveres de casa. Não fazia diferença se você era português, chinês, indiano ou judeu, porque me lembro que no Colégio La Salle eu tinha outros dois grandes amigos: John Arculli e Robin Prish. Eu era português, John era indiano e Robin era judeu. Estávamos fazendo nossa matrícula em 1938/39 e, naquela época, quando você começa a frequentar o último ano do colégio, você também percebe que não demorará muito para começar a trabalhar no mundo.

Lembro-me de uma garota muito simpática no Convento de Maryknoll que costumava ficar na entrada da escola das meninas quando voltávamos da escola dos meninos. Costumávamos nos encontrar e conversar – havia uma atração, eu acho. A garota costumava tocar a campainha quando eu não estava em casa, e minha mãe reconhecia sua voz e a repreendia por me ligar demais.

Morávamos no lado esquerdo da estrada que subia em direção a Kowloon Tong. Onde hoje existem tantos prédios de vários andares, naquela época, em 1932, havia apenas pequenas colinas e arrozais. E a estrada principal, onde estavam construindo novas casas, não muito longe de onde a nova Igreja de Santa Teresa acabara de ser construída. Não muito longe da Igreja de Santa Teresa, uma nova faculdade estava sendo construída, chamada La Salle College. A faculdade ficava no alto de uma colina – eram necessários cerca de 70 degraus da Rua Boundary até o grande prédio onde ficava a escola secundária. Era administrada pelos Irmãos Cristãos. Meus irmãos , e eu costumávamos ir a pé para a escola todos os dias. A caminhada levava meia hora.

Foi nessa época que o terceiro irmão da família, , que tinha então cerca de 22 ou 23 anos e trabalhava no Banco, adoeceu. Um dos médicos do Banco, um inglês, veio examiná-lo e disse que ele poderia ter alguns sinais de problemas pulmonares, mas não conseguia diagnosticar o problema de Carlinho. Meu irmão foi ele quem achou que Carlinho não tinha o que o médico pensava, então ele insistiu que procurássemos uma segunda opinião de um médico chinês, formado pela Universidade de Hong Kong, que trabalhava no Hospital Kowloon, não muito longe de nossa casa.

Este médico chinês veio examinar Carlinho e disse que ele poderia estar com febre tifoide. Nossa mãe ficou muito ansiosa e chamou outro médico chinês para tratar Carlinho à moda chinesa. Ele usou um pouco de pó e disse que Carlinho estava com febre tifoide. Infelizmente, era tarde demais, Carlinho estava em coma. O médico o internou no Hospital Kowloon para observação, e naquela mesma noite ele morreu. Foi a primeira vez que tive a experiência de alguém que eu conhecia tão bem falecer. Sua morte impactou toda a família, pois ele foi o primeiro dos meninos a morrer. Minha mãe disse que ele era o mais bonito da família.

Ele tinha uma namorada, Pam Yvanovich, que morava perto da nossa casa. Ela era a mais velha das meninas da família. Minha irmã e Pam costumavam andar juntos e provavelmente foi assim que Carlinho a conheceu em casa, se apaixonou por ela e ficaram noivos. Meu outro irmão ajudou-a a superar a perda de Carlinho, cuidou dela e se casou com ela em 1940; mais tarde, eles tiveram cinco meninos e uma menina.

A casa na Avenida Soares tinha dois andares. Era anexa ao número 9 da Avenida Soares, que era ocupada por uma família portuguesa, os Sequeiras. Ao lado da nossa, o número 13, era ocupado por outra família portuguesa chamada Barros. Entre esta casa e a próxima havia uma também ocupada por uma família portuguesa chamada Guterres. Ao lado da casa dos Guterres morava a família Yvanovich, de onde vinha a Pam. Não ficávamos muito longe dela. Era bom que estivéssemos juntos e, lá também, tínhamos muitos jovens que formavam um grupo muito bom e feliz. Costumávamos nos divertir muito juntos, nadando e fazendo piqueniques. Numa multidão como aquela, você estava sempre em ótima companhia. Éramos um grupo jovem e saudável. Eu era o mais novo daquele grupo de meninas e meninos da rua que jogavam rounders, tênis, faziam trilhas – todas aquelas coisas que os jovens faziam juntos.

Eu não gostava muito de vida noturna. Meus irmãos mais velhos eram bons esportistas. Toda vez que eles tinham um jogo, íamos assisti-los – torcendo por eles, acompanhando-os e assistindo-os jogar. Eddie jogava críquete na universidade. Ele se tornou um jogador muito bom e jogou por Hong Kong – graças a ele, Gerry e eu também começamos a jogar críquete e formamos um time na escola, jogamos em escolas combinadas e começamos a nos destacar como bons jogadores de críquete.

Também jogávamos hóquei, tênis, natação e futebol pela escola. Toda a nossa vida girava em torno do esporte – fazíamos os estudos normais, mas nada que desse uma bolsa de estudos. Bastava passar de uma turma para outra.

Virei coroinha, servindo missa na igreja e indo à missa de manhã com minha mãe – voltando, tomando café da manhã e indo para a escola. Era uma vida muito saudável, cheia de esportes, muita felicidade em casa. Gerry e eu éramos como gêmeos. Na verdade, eu seria maior que Gerry. Ele não gostava muito de estudar – uma turma nos separava e ele era dois anos mais velho que eu. Ele era um dos melhores desportistas de Hong Kong na comunidade portuguesa, um bom corredor, jogador de críquete, jogador de hóquei, jogador de tênis, jogador de softball e um ótimo nadador. Ele era alguém que todo jovem jogador português aspiraria ser.