The great typhoon of 1874

by Stuart Braga

Edited version of an article published in the Casa Down Under Newsletter, vol 20 Issue 4, Sept 2008

A grande calamidade. So begins the report of the session of the Leal Senado (the Macau Council) of 29 September 1874, quoted by the prolific Macau historian, Father Manuel Teixeira. Writing in 1974 on the centenary of the typhoon, Teixeira described it as the most destructive ever experienced in the history of Macau. As cyclones are to Northern Australia and hurricanes to the southern United States, so typhoons are to the South China Coast. Over the centuries they have brought death and disaster on a huge scale. The horroroso tufão of 1738 was the greatest disaster to have befallen Macau up to that time. About a century later, two typhoons created havoc only a year apart, in 1847 and 1848. By 1847, meteorological records had commenced, and the mercury dropped to 745 mm. The following July, another grande e violento tufão swept the coast of South China.

Macau had already suffered substantial loss of population with large numbers leaving for Hong Kong, occupied by Britain since 1842. Typhoons grew worse, with more buffeting in the next 25 years from typhoons which took barometric readings in Macau down to 726mm in 1862 and 717mm in 1871. Hong Kong was relatively protected from the worst violence of typhoons because of its sheltered harbour. However Macau faced the full force of a typhoon sweeping in from the South China Sea. A scientific journal in 1874 observed, ‘Macau fares worst, for it is situated precisely where the typhoon is arrested by the high land of the coast.‘

The article went on to point out that the typhoon had crossed from Hong Kong to Macau in half the time taken by the typhoon of 1871. The low point of the barometer occurred in Hong Kong at 2.15am and in Macau at 3.15am. In 1871 the typhoon had taken more than two hours to reach Macau from Hong Kong. So Macau was hit in 1874 twice as fast and even harder than it had been three years earlier.

On this occasion, the barometer in Macau dropped to 709mm, the lowest pressure ever recorded at that time in China . While Hong Kong endured a terrific battering, Macau was almost obliterated. C.A. Montalto de Jesus, then a boy of eleven living in nearby Hong Kong, wrote about it a quarter of a century later.

‘As if nature too were bent on the downfall of Macao, a terrific typhoon, its very centre, swept over the ill-fated colony on the memorable 22nd of September 1874; and a fateful shift of the wind from north to east, at the equinoctial spring tide doomed the fairest part of the city to the full havoc of cyclonic blasts and waves. Battered, flooded, Macao was at the same time assailed by pirates.‘

Fires broke out throughout the city, possibly lit by arsonists intent on forcing people to flee from their houses so that they might be looted more easily. Montalto de Jesus went on,

‘the lurid glare revealed many an imminent peril in that night of unspeakable horror and tribulation.‘

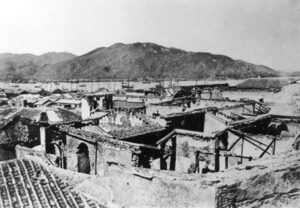

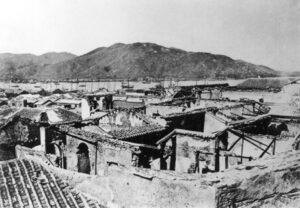

The official report, dated 23 October 1874, lists street by street Chinese houses lost. They totalled 1,172 (4). Between 4,000 and 5,000 people died and 2,000 fishing and trading craft were lost. On Taipa more than 1,000 bodies were found and another 500 on Coloane, chiefly of fishermen. The value of houses, goods and ships lost came to roughly $2 million, a vast sum at that time(3).

On 22 September 1874,

‘It was a very hot and still night and people were out in the Praia Grande in search of a little fresh air. A full moon ... filled the night sky. As people began to make their way home, it started to rain heavily and a strong wind started up. Everyone firmly secured and locked their doors and windows ... Never had there been such a strong typhoon. The sea level rose so high that a lorcha [a light vessel with a European hull, and the rigging of a Chinese junk] was washed up close to the cathedral.‘

The dead were buried in a new cemetery opened for the purpose on Taipa. So great was the devastation that there was speculation that an earthquake probably occurred at the same time as the typhoon. [ttkeyword=”(5)”]Nature, ibid, p168[/tt].

In those days there were no weather forecasts or typhoon warnings. These came later, and the old typhoon signals – 10 large black geometric shapes – are still housed on Guia. They used to be hoisted on a mast when a typhoon threatened, but this elementary system has long since been replaced by radio, television and the Internet. So this typhoon struck very quickly and without warning. Augusto Nolasco told Graciete Batalha something of what happened.

Things grew worse.

‘Roofs were blown off and houses collapsed and a great fire swept through Santo Antonio.‘ Nolasco went on to recount the story of an old couple whose house was unroofed, and as they fled to the church seeking sanctuary, were robbed by pirates. Next morning they found their house destroyed by fire. They ended their days destitute. (6)

Most of the 2,000 vessels lost were fishing craft, and the Chinese boat people were all but wiped out. Larger vessels were lost too. A Portuguese gunboat, Principe Carlos, was landed in a paddy field 14 miles away to the south 3, and Teixeira(7) names three other ships that were driven ashore or suffered damage in the Porto Interior.

The loss of ships in Hong Kong was greater than that in Macau, because the commerce of Macau had diminished during the previous thirty years. The London newspaper The Times reported on 30 September that five ships had been sunk, six were missing, three had run aground and another nine dismasted. (30 September 1874). A week later on 5 October the paper printed another long list of vessels damaged which had struggled back to Hong Kong harbour for repairs. It is interesting to note that the British papers reported only the loss of shipping. There is no mention of loss of lives or property. The British were concerned only with commerce.

Montalto de Jesus went on, ‘the disastrous typhoon consummated the ruin of the Macanese’. In the next two years, the Catholic population of Hong Kong increased from 4,520 to 5,250. It is likely that much of this increase, of 730 people or 15%, is the result of an influx of refugees from the stricken Portuguese colony. The enrolment of St Joseph’s College, Hong Kong, increased greatly for the same reason. However, whereas the earlier Portuguese immigration of the 1840s was readily absorbed by the rapidly growing Hong Kong, this large influx could not readily be accommodated and they became for many years an underclass. This led to social tensions discussed at some length by the fiery young J.P. Braga, who in 1895 wrote a hard-hitting pamphlet against the injustices experienced by the Portuguese community: The rights of aliens in Hongkong. It was the beginning of a long and distinguished public career.

In Macau there was a detailed report on damage to churches and public buildings. The Bishop’s Palace was largely destroyed and church archives were lost. The churches of São Lázaro, Santo Agostinho, São Domingos and Santo António all suffered heavy damage, particularly Santo António which was severely damaged by fire. The cathedral too suffered major structural damage.(8)

Nevertheless, Macau would fulfil a vital role between 1942 and 1945 when more than 10,000 British and American people flocked there during World War II, as a calamity far greater than any typhoon overtook Hong Kong – the Japanese Occupation. If Macau had not been there for these refugees, their situation would have been unimaginably desperate. Macau, abandoned by the British for a century, generously gave them relief and safety in their time of need.

A note on sources. The Macau Collection Room of the Macau Central Library, Av. Conselheiro Ferreira de Almeida, contains all the local sources used. I am grateful to Marie Imelda MacLeod, Directora do Arquivo Histórico, for her assistance in locating printed and photographic sources there. Other printed sources are in the National Library of Australia, notably the JM Braga Collection.

I appreciate also the efforts made by António M. Jorge da Silva in enhancing the photographs.

Stuart Braga

O grande tufão de 1874

Stuart Braga

Versão editada de um artigo publicado na Casa Down Under Newsletter, vol 20 Edição 4, Set 2008

Uma grande calamidade. Assim começa o relatório da sessão do Leal Senado (o Conselho de Macau) de 29 de Setembro de 1874, citado pelo prolífico historiador de Macau, Padre Manuel Teixeira. 1) Escrevendo em 1974 no centenário do tufão, Teixeira descreveu-o como o mais destrutivo já experimentado na história de Macau. Como os ciclones estão no norte da Austrália e furacões no sul dos Estados Unidos, os tufões estão na costa sul da China. Ao longo dos séculos, eles trouxeram morte e desastre em grande escala. O horroroso tufão de 1738 foi o maior desastre que aconteceu em Macau até aquele momento. Cerca de um século depois, dois tufões criaram estragos com apenas um ano de diferença, em 1847 e 1848. Em 1847, os registros meteorológicos começaram e o mercúrio caiu para 745 mm. No mês de julho seguinte, outro grande e violento tufão varreu a costa do sul da China.

Macau já tinha sofrido perdas substanciais de população, com um grande número partindo para Hong Kong, ocupado pela Grã-Bretanha desde 1842. Os tufões pioraram, com mais golpes nos próximos 25 anos a partir de tufões que levaram leituras barométricas em Macau para 726 mm em 1862 e 717 mm em 1871. Hong Kong estava relativamente protegida da pior violência dos tufões por causa de seu porto abrigado. No entanto, Macau enfrentou toda a força de um tufão que varreu o Mar do Sul da China. Uma revista científica em 1874 observou: “Macau se sai pior, pois está situado precisamente onde o tufão é preso pela alta terra da costa”. O artigo prosseguia salientando que o tufão tinha atravessado de Hong Kong para Macau em metade do tempo levado pelo tufão de 1871. O ponto mais baixo do barómetro ocorreu em Hong Kong às 2h15 e em Macau às 3h15. Em 1871, o tufão demorou mais de duas horas a chegar a Macau, vindo de Hong Kong. Assim, Macau foi atingido em 1874 com o dobro da velocidade e com ainda mais força do que três anos antes.

Nesta ocasião, o barómetro em Macau caiu para 709 mm, a menor pressão alguma vez registada na época na China . Enquanto Hong Kong sofreu uma terrível surra, Macau foi quase obliterada. C.A. (em inglês). Montalto de Jesus, então um menino de onze anos que vive nas proximidades de Hong Kong, escreveu sobre isso um quarto de século depois.

‘Como se a natureza também estivesse inclinada à queda de Macau, um terrível tufão, o seu centro, varreu a malfadada colhendada no memorável 22 de Setembro de 1874; e uma fatídica mudança do vento de norte para leste, na maré equinocial da primavera condenou a parte mais justa da cidade ao caos total das explosões e ondas ciclônicas. Maltratado, inundado, Macau foi ao mesmo tempo assaltada por piratas.‘

Incêndios deflagraram por toda a cidade, possivelmente provocados por incendiários com a intenção de obrigar as pessoas a fugir das suas casas para que pudessem ser saqueadas mais facilmente. Montalto de Jesus continuou:

“O clarão lúgubre revelou muitos perigos iminentes naquela noite de horror e tribulação indizíveis”.

O relatório oficial, datado de 23 de outubro de 1874, lista, rua a rua, as casas chinesas perdidas. Totalizaram 1.172 (4). Entre 4.000 e 5.000 pessoas morreram e 2.000 embarcações de pesca e comércio perderam-se. Mais de mil corpos foram encontrados na Taipa e outros 500 em Coloane, sobretudo de pescadores. O valor das casas, mercadorias e navios perdidos atingiu aproximadamente 2 milhões de dólares, uma enorme quantia na época(3).

Taipa. Tão grande foi a devastação que houve especulação de que um terremoto provavelmente ocorreu ao mesmo tempo que o tufão. (5).

Naqueles dias não havia previsões meteorológicas ou avisos de tufão. Estes vieram mais tarde, e os antigos sinais de tufão – 10 grandes formas geométricas pretas – ainda estão alojados na Guia. Eles costumavam ser içados em um mastro quando um tufão ameaçava, mas esse sistema elementar há muito tempo foi substituído por rádio, televisão e Internet. Então, este tufão atingiu muito rapidamente e sem aviso prévio. Augusto Nolasco contou a Graciete Batalha algo do que aconteceu.

A 22 de setembro de 1874,

‘Estava uma noite muito quente e calma, e as pessoas estavam na Praia Grande à procura de um pouco de ar fresco. A lua cheia... preenchia o céu noturno. Quando as pessoas começavam a regressar a casa, começou a chover torrencialmente e começou a soprar um vento forte. Todos fecharam e trancaram firmemente as suas portas e janelas... Nunca houve um tufão tão forte. O nível do mar subiu tanto que uma lorcha [uma embarcação ligeira com casco europeu e cordame de junco chinês] foi levada para perto da catedral.‘

As coisas pioraram.

“Telhados foram arrancados, casas ruíram e um grande incêndio varreu Santo António.” Nolasco continuou a contar a história de um casal de idosos cuja casa estava sem telhado e, ao fugirem para a igreja em busca de refúgio, foram assaltados por piratas. Na manhã seguinte, encontraram a sua casa destruída pelo fogo. Terminaram os seus dias na miséria. (6)

A maioria das 2.000 embarcações perdidas eram embarcações de pesca, e os barqueiros chineses foram praticamente dizimados. Embarcações maiores também foram perdidas. Uma canhoneira portuguesa, o príncipe Carlos, foi encalhada num arrozal a 22 quilómetros a sul, e Teixeira cita três outros navios que foram encalhados ou sofreram danos no Porto Interior.

A perda de navios em Hong Kong foi maior do que em Macau, porque o comércio de Macau tinha diminuído nos trinta anos anteriores. O jornal londrino The Times noticiou a 30 de setembro que cinco navios tinham sido afundados, seis estavam desaparecidos, três encalharam e outros nove perderam o mastro (30 de setembro de 1874). Uma semana depois, a 5 de outubro, o jornal publicou outra longa lista de navios danificados que tinham lutado para regressar ao porto de Hong Kong para reparação. É interessante notar que os jornais britânicos apenas reportaram a perda de navios. Não há qualquer menção à perda de vidas ou de bens. Os britânicos estavam apenas preocupados com o comércio.

Montalto de Jesus prosseguiu: “o desastroso tufão consumou a ruína dos macaenses” . Nos dois anos seguintes, a população católica de Hong Kong aumentou de 4.520 para 5.250. É provável que grande parte deste aumento, de 730 pessoas ou 15%, seja o resultado de um afluxo de refugiados da colónia portuguesa devastada. As matrículas no St. Joseph’s College, em Hong Kong, aumentaram consideravelmente pelo mesmo motivo. No entanto, enquanto a imigração portuguesa anterior, na década de 1840, foi prontamente absorvida por Hong Kong, em rápido crescimento, este grande afluxo não pôde ser facilmente acomodado e tornaram-se, durante muitos anos, uma subclasse. Isto levou a tensões sociais discutidas longamente pelo jovem e impetuoso J.P. Braga, que em 1895 escreveu um panfleto mordaz contra as injustiças sofridas pela comunidade portuguesa: Os direitos dos estrangeiros em Hong Kong. Foi o início de uma longa e distinta carreira pública.

Em Macau houve um relatório detalhado sobre os danos em igrejas e edifícios públicos. O Palácio do Bispo foi em grande parte destruído e os arquivos da igreja perderam-se. As igrejas de São Lázaro, Santo Agostinho, São Domingos e Santo António sofreram graves danos, nomeadamente Santo António que ficou gravemente danificado pelo incêndio. A catedral sofreu também grandes danos estruturais.

Quando o Leal Senado falou de “uma grande calamidade”, não sabiam de metade. Hong Kong recuperou bastante rapidamente, mas Macau demorou muitas décadas. A economia já estava num mau estado e, com o êxodo da população, as coisas pioraram. Montalto de Jesus citou com pesar uma previsão pessimista feita logo após a criação de Hong Kong em 1842: que Macau se tornaria uma rocha nua onde os pescadores estenderiam as suas redes para secar. 3 Seriam necessários mais de cem anos para que a prosperidade regressasse a Macau, e ainda mais para que os casinos de hoje trouxessem vasta riqueza.

No entanto, Macau viria a desempenhar um papel vital entre 1942 e 1945, quando mais de 10.000 britânicos e americanos se reuniram para lá durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial, quando uma calamidade muito maior do que qualquer tufão atingiu Hong Kong – a ocupação japonesa. Se Macau não estivesse presente para estes refugiados, a sua situação teria sido inimaginavelmente desesperada. Macau, abandonado pelos britânicos durante um século, ofereceu-lhes generosamente alívio e segurança no seu momento de necessidade.

No entanto, Macau viria a desempenhar um papel vital entre 1942 e 1945, quando mais de 10.000 britânicos e americanos se reuniram para lá durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial, quando uma calamidade muito maior do que qualquer tufão atingiu Hong Kong – a ocupação japonesa. Se Macau não estivesse presente para estes refugiados, a sua situação teria sido inimaginavelmente desesperada. Macau, abandonado pelos britânicos durante um século, ofereceu-lhes generosamente alívio e segurança no seu momento de necessidade.

Stuart Braga