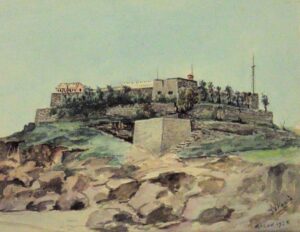

MONTE FORT

by Dr Stuart Braga

Originally published in Casa de Macau Australia News, April 2014, Vol 27 Issue 3

The original name of the fort was Fortaleza de Nossa Senhora do Monte de São Paulo, in English: Fortress of Our Lady of the Mount of St. Paul. The name suggests a religious origin. So indeed it was. Macau was the furthest outpost of a far-flung Portuguese empire that stretched along the African coast, with substantial strongpoints at Ormuz in the Persian Gulf at Daman in India.

Further east was an immensely strong fort at Malacca. All these were built as soon as the Portuguese arrived. Macau, further east again, was unfortified for more than fifty years after its settlement by Portuguese traders in 1557. This is because it was a trading post pure and simple, not a springboard for the invasion of South China. The Chinese Empire was far too strong for anything like that to be attempted, even if the Portuguese had the strength to attempt it. They did not, because Portugal had already over-reached its resources, and its great empire, with at least forty forts, had begun to wane by the late 16th century.

The main enemies were the Dutch, who gradually wrested control of much of the trade of the Far East from the Portuguese, culminating in their capture of Malacca in 1641 after a three-year blockade and siege. It was the third attempt. Clearly, their eyes were set on defenseless Macau. In Macau, the Jesuits had established St Paul’s College in 1565. Like the apostle Paul, they saw themselves on the cusp of an epic missionary journey. Macau was to be the springboard of evangelism in this vast heathen empire. If the Dutch, firmly Protestant, and bitterly anti-Catholic, seized Macau for its trade, all would be lost. Macau had therefore to be defended.

Small forts along the Praya Grande would not repel a determined attack, so the Jesuits determined to build a much larger fort on top of the hill overlooking the small town below.

The Chinese authorities were dubious about this, lest these “Western barbarians” try to assert a greater degree of control than the Chinese were prepared to permit.

There was indeed a Dutch attack in 1622, but it was repelled, although the fort was not finished. Thereafter, the Chinese allowed the completion of the fort, seeing that it was intended to defend Macau against another group of barbarians, who might be much more difficult to deal with.

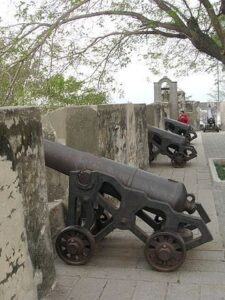

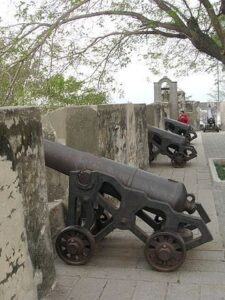

You step onto the escalator taking you up into the Macau Museum and you glide past an ancient wall that looks as though it has always been there. Once inside, you see a fine display on the history of the various cultures that have shaped modern Macau. If you ever go to Macau, this major museum is a must. Escalators take you up several levels, and eventually you step out onto the flat top of the ancient fort. Around you are battlements and embrasures, some with cannon aimed out over the city below. These are not the originals, dating from about 1860, about 250 years after the fort was completed.

Therefore Monte Fort was finished in 1626, with four great bastions built high above the glacis below. This was a steep slope, left bare of vegetation and construction, up which attackers would have to fight against heavy fire from above. In 17th century terms, this fort was almost impregnable. However, its strength was never tested, for the fort saw no military action at all, as the Dutch left Macau alone from then on. In 1638, the first Governor of Macau, Francisco de Mascarenhas, expelled the Jesuits and the fort became the headquarters of the Governor of Macau until 1749.

Eventually, in 1964, a meteorological station was installed there.

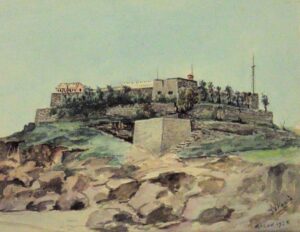

Guia Fort, its height greatly exaggerated, is to the left, Monte Fort to the right in this engraving by Thomas Allom, published in 1840. In the foreground is a Chinese funeral.

The escalator leading to the museum was installed in the 1990s. For the previous 370 years there was only one way to reach Monte Fort. This was up the steep Calcada do Monte from the street below. This led to a small, well-protected entrance, inside which another steep path led to a small chapel; protection of this fort was spiritual as well as temporal.

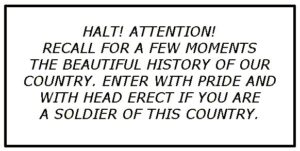

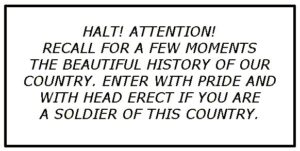

On the wall beside the gateway is a bronze plaque that appears to date from the early twentieth century. Translated from the Portuguese, it reads:

Taking a few steps inside the fort leaves you in no doubt about its antiquity. At the first turn of the ramp is a splendid granite memorial dated 1626. It is comprised of four stones. One carries the royal arms of Portugal, another a bust of St Paul, his head adorned with a halo. In a strange combination of symbols, a drawn sword rests on his right shoulder.

The impression given by these two tablets, one bronze, the other granite, is one of sustained might and invincibility.

FORTALESA DE MONTE

Dr Stuart Braga

Publicado originalmente em Casa de Macau Austrália News, abril de 2014, Vol 27 Edição 3

Você pisa na escada rolante levando você ao Museu de Macau e passa por uma antiga parede que parece que sempre esteve lá. Uma vez lá dentro, você vê uma bela exibição na história das várias culturas que moldaram a moderna Macau. Se alguma vez for a Macau, este grande museu é obrigatório. Escadas rolantes levam você a vários níveis, e eventualmente você pisa no topo plano do antigo forte. Ao seu redor há ameias e abrangências, algumas com canhões voltados para a cidade abaixo. Estes não são os originais, datados de cerca de 1860, cerca de 250 anos após a conclusão do forte.

O nome original do forte foi Fortaleza de Nossa Senhora do Monte de São Paulo, em inglês: Fortaleza de Nossa Senhora do Monte de São Paulo. – Paul. O nome sugere origem religiosa. Então, de fato, foi. Macau era o posto avançado mais distante de um império português distante que se estendia ao longo da costa africana, com pontos fortes substanciais em Ormuz, no Golfo Pérsico, em Daman, na índia.

Mais a leste era um forte fort imensamente forte em Malaca. Tudo isto foi construído assim que os portugueses chegaram. Macau, mais a leste novamente, foi intristificada por mais de cinquenta anos após o seu assentamento por comerciantes portugueses em 1557. Isso ocorre porque era um post comercial puro e simples, não um trampolim para a invasão do sul da China. O Império Chinês era forte demais para que algo assim fosse tentado, mesmo que os portugueses tivessem força para tentar. Eles não o fizeram, porque Portugal já tinha ultrapassado os seus recursos, e o seu grande império, com pelo menos quarenta fortes, tinha começado a diminuir no final do século XVI.

Os principais inimigos foram os holandeses, que gradualmente arrancaram o controle de grande parte do comércio do Extremo Oriente dos portugueses, culminando em sua captura de Malaca em 1641 após um bloqueio de três anos e cerco. Foi a terceira tentativa. Claramente, seus olhos estavam postos em Macau indefesa. Em Macau, os jesuítas tinham estabelecido o Colégio de São Paulo em 1565. Como o apóstolo Paulo, eles se viam à beira de uma jornada missionária épica. Macau deveria ser o trampolim do evangelismo neste vasto império pagão. Se os holandeses, firmemente protestantes e amargamente anticatólicos, tomassem conta de Macau para o seu comércio, tudo seria perdido. Macau teve que ser defendida.

Pequenos fortes ao longo da Praya Grande não repeliriam um ataque determinado, então os jesuítas decidiram construir um forte muito maior no topo da colina com vista para a pequena cidade abaixo.

As autoridades chinesas duvidavam disso, para que esses “bárbaros ocidentais” não tentassem afirmar um maior grau de controle do que os chineses estavam preparados para permitir.

Houve de fato um ataque holandês em 1622, mas foi repelido, embora o forte não tenha terminado. Depois disso, os chineses permitiram a conclusão do forte, visto que se destinava a defender Macau contra outro grupo de bárbaros, que poderia ser muito mais difícil de lidar.

Portanto, o Monte Fort foi concluído em 1626, com quatro grandes bastiões construídos acima das glaciares abaixo. Esta era uma encosta íngreme, à esquerda de vegetação e construção, acima que os atacantes teriam que lutar contra o fogo pesado de cima. Em termos do século XVII, este forte era quase inexpugnável. No entanto, sua força nunca foi testada, pois o forte não viu nenhuma ação militar, já que os holandeses deixaram Macau sozinho a partir de então. Em 1638, o primeiro governador de Macau, Francisco de Mascarenhas, expulsou os jesuítas e o forte tornou-se a sede do governador de Macau até 1749.

Eventualmente, em 1964, uma estação meteorológica foi instalada lá.

O Forte da Guia, sua altura é muito exagerada, à esquerda, o Forte do Monte, à direita, nesta gravura de Thomas Allom, publicado em 1840. Em primeiro plano está um funeral chinês.

A escada rolante que leva ao museu foi instalada na década de 1990. Nos últimos 370 anos, havia apenas uma maneira de chegar ao Monte Fort. Este foi até o íngreme Calcada do Monte da rua abaixo. Isso levou a uma entrada pequena e bem protegida, dentro da qual outro caminho íngreme levava a uma pequena capela; a proteção deste forte era tanto espiritual quanto temporal.

Na parede ao lado da porta está uma placa de bronze que parece datar do início do século XX. Traduzido do português, lê-se:

On the wall beside the gateway is a bronze plaque that appears to date from the early twentieth century. Translated from the Portuguese, it reads:

Ao dar alguns passos para o interior do forte, não restam dúvidas sobre a sua antiguidade. Na primeira curva da rampa, encontra-se um esplêndido memorial em granito datado de 1626. É composto por quatro pedras. Uma ostenta o brasão real de Portugal, a outra, um busto de São Paulo, com a cabeça adornada por uma auréola. Numa estranha combinação de símbolos, uma espada desembainhada repousa sobre o seu ombro direito.

A impressão dada por estas duas placas, uma de bronze e outra de granito, é de um poder e invencibilidade sustentados.