Patuá Basics

Noções Básicas de Patuá

“Riri” d’Assumpção

from unpublished Anecdotes from Old Macau.

“Riri” d’Assumpção

de anedotas inéditas da antiga Macau.

Personal Pronouns

Pronomes pessoais

Tenses

Tenses were generated simply with a prefix: for the past tense, ja  from the Portuguese word já = already; for the present tense, ta (short for Portuguese está); and for the future tense, logo

from the Portuguese word já = already; for the present tense, ta (short for Portuguese está); and for the future tense, logo  (from the Portuguese logo = “soon”, but pronounced more like the English word “logo”).

(from the Portuguese logo = “soon”, but pronounced more like the English word “logo”).

Thus from vai = go we have ta vai = going, ja vai = went or gone, and logo vai = will go.

(There is a similarity to the use of a suffix in Cantonese to denote tenses: choh, kun and wui for the past, present and future tenses respectively, but I have no idea whether the evolution of grammar in the patuá was influenced in any way by the Cantonese dialect.)

Tempos verbais

Os tempos verbais eram gerados simplesmente com um prefixo: para o pretérito, ja do português já ; para o presente, ta (abreviação do português está); e para o futuro, logo (do português logo =”em breve”, mas pronunciado mais como a palavra inglesa “logo”).

Thus from vai = go we have ta vai = going, ja vai = went or gone, and logo vai = will go.

Assim, de vai temos ta vai = indo, ja vai = foi ou ido, e logo vai = irá.

(Há uma semelhança com o uso de um sufixo em cantonês para denotar tempos verbais: choh, kun e wui para os tempos passado, presente e futuro, respectivamente, mas não tenho ideia se a evolução da gramática no patuá foi influenciada de alguma forma pelo dialeto cantonês.)

Pronunciation

In Macanese the letter “R”, at the end of most Portuguese verbs, is never pronounced (probably because of its difficulty for many Asians). Thus the verbs “abrir” (to open), “comer” (to eat) and “dormir” (to sleep) are pronounced as “abri”. “comeh” and “dormi” respectively, with the emphasis (always?) on the last syllable.

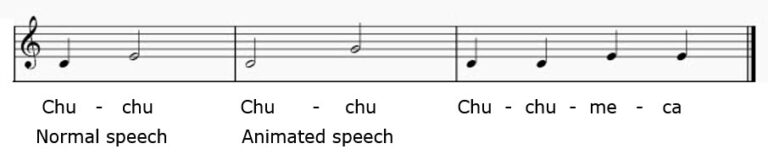

A feature of the patuá is that it is delivered in a sing-song voice but, unlike the Chinese dialects, the patuá does not rely on tonality to convey meaning. The accented syllable(s) are always delivered at a higher pitch.

Thus chuchu  (to poke or prod) is never pronouced in a flat monotone as in “choo-choo train” in English but has its second syllable delivered some 4 or 5 semitones above the first or, with heightened animation, up to 8 semitones.

(to poke or prod) is never pronouced in a flat monotone as in “choo-choo train” in English but has its second syllable delivered some 4 or 5 semitones above the first or, with heightened animation, up to 8 semitones.

Chuchumeca  (busybody, stickybeak) has the first two syllables at the same lower pitch and the third and fourth at a higher pitch.

(busybody, stickybeak) has the first two syllables at the same lower pitch and the third and fourth at a higher pitch.

Pronúncia

Em macaense, a letra “R”, no final da maioria dos verbos portugueses, nunca é pronunciada (provavelmente devido à dificuldade que muitos asiáticos enfrentam ao pronunciá-la). Assim, os verbos “abrir”, “comer” e “dormir” são pronunciados como “abri”, “comeh” e “dormi”, respectivamente, com a ênfase (sempre?) na última sílaba.

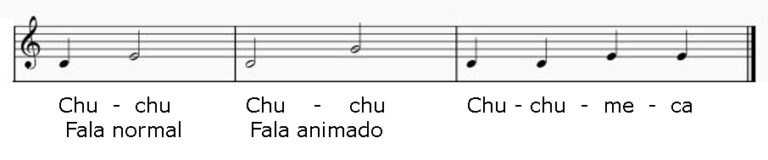

Uma característica do patuá é que ele é pronunciado em um tom cantado, mas, diferentemente dos dialetos chineses, o patuá não depende da tonalidade para transmitir significado. A(s) sílaba(s) acentuada(s) são sempre pronunciadas em um tom mais agudo.

Assim, “chuchu”  (cutucar ou provocar) nunca é pronunciado em um tom monótono como em “choo-choo train” em inglês, mas tem sua segunda sílaba pronunciada cerca de 4 ou 5 semitons acima da primeira ou, com maior animação, até 8 semitons.

(cutucar ou provocar) nunca é pronunciado em um tom monótono como em “choo-choo train” em inglês, mas tem sua segunda sílaba pronunciada cerca de 4 ou 5 semitons acima da primeira ou, com maior animação, até 8 semitons.

Chuchumeca  (intrometido, bisbilhoteiro) tem as duas primeiras sílabas no mesmo tom mais baixo e a terceira e a quarta em um tom mais alto.

(intrometido, bisbilhoteiro) tem as duas primeiras sílabas no mesmo tom mais baixo e a terceira e a quarta em um tom mais alto.

Grammar

The patuá was used as the lingua franca of trade in the Far East and had a small vocabulary and rudimentary grammar and syntax. There was no distinction between adjectives and adverbs (anticipating by a couple of centuries an unfortunate trend in some countries in the usage of English today); thus vagar denotes both slow and slowly. Repetition was used for plurals and superlatives: the plural of filho (son), for example, is filho filho; very slowly is vagar vagar.

Gramática

O patuá era usado como língua franca do comércio no Extremo Oriente e tinha um vocabulário pequeno e gramática e sintaxe rudimentares. Não havia distinção entre adjetivos e advérbios (antecipando em alguns séculos uma tendência infeliz no uso do inglês em alguns países hoje em dia); assim, vagar denota tanto lento quanto lentamente. A repetição era usada para plurais e superlativos: o plural de filho, por exemplo, é filho filho; muito lentamente é vagar vagar.

Spelling

The patuá was only spoken so there is no consistency in spelling; apart from minor differences in pronunciation, people tend to spell phonetically according to the principal language in which they received education. Thus people from Macau might spell the famous Macanese dish minchi while those from Hong Kong might spell it minchy.

Ortografia

O patuá era apenas falado, portanto não há consistência na grafia; além de pequenas diferenças de pronúncia, as pessoas tendem a escrever foneticamente de acordo com o idioma principal em que foram educadas. Assim, pessoas de Macau podem escrever o famoso prato macaense minchi, enquanto pessoas de Hong Kong podem escrevê-lo minchy.