'An Unexampled Calamity'

The Hong Kong Plague of 1894

by Stuart Braga

Article originally published in Casa de Macau Australia Bulletin

‘Without exaggeration I may assert that so far as trade and commerce are concerned the plague has assumed the importance of an unexampled calamity. So stated the dispatch of the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir William Robinson, to the Secretary of State for Colonies in London on 20 June 1894.(1)

He meant that there was no other example of so great a calamity. The calamity was a serious outbreak of bubonic plague, which brought Hong Kong to its knees. Strangely, although it also devastated Canton, it left Macau largely intact. Sir William might have added that it was a vast human tragedy as well, for several thousand people, mostly poor Chinese, died, and more than 100,000 fled in panic to their home villages.

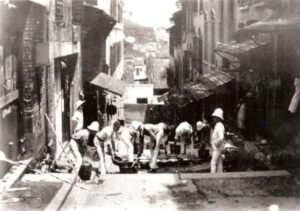

An officer of the Kings Shropshire Light Infantry supervises troops cleaning the streets in Tai Ping Shan

It appears that before the disease reached Hong Kong it had broken out in Canton in January that year, and by June it had accounted for some 80,000 deaths. Rapidly moving down-river, it first appeared in the Tai Ping Shan district in the early months of 1894. At that time, Tai Ping Shan, high above Kennedy Town to the west of Hong Kongs Central District, was a crowded squalid settlement of Chinese workers. There was no water supply or sanitation, and living conditions were utterly filthy.

In Tai Ping Shan there was panic and hysteria, for the outcome in the great majority of cases was an agonising death after three days of suffering. A graphic description of the symptoms of bubonic plague was given by M. Wilm in his Report of Plague in Hong Kong compiled in 1896. Wilm observed that

“at the outset of the disease the tongue usually became swollen, bright red at the tip and edges and was covered with a greyish white fur. Usually, on the second or third day of the disease, the fur became brownish or black, and dried in a crust. The tongue becomes cracked and fissured … The lips soon became dry and often fissured, the mucous membrane of the mouth and the pharynx was usually bright red. The appetite disappeared. There was frequently uncontrollable vomiting and great thirst.”

He goes on, but the details are too distressing to relate here.

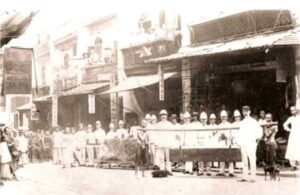

Soldiers of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry supervise the removal of a coffin of a plague victim, carried on a pole by coolies.

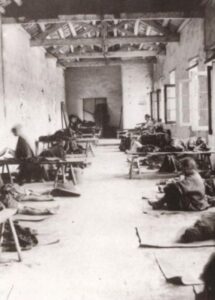

On 10th May 1894 Hong Kong was declared an infected port and within the space of a few weeks the administration was faced with an epidemic of great magnitude. By July there had been 2442 deaths. Hospitals were quickly established on board the naval ship, Hygeia, at Kennedy Town Police Station and at the Kennedy Town glass works. The first two were run by European staff whilst the third was manned by Chinese personnel of the Tung Wah hospital. The Governor told his superior in London that ‘it was deemed advisable to give the Chinese doctors a free hand at first. In any case, it is difficult to persuade the Chinese to report cases of sickness and their foolish and violent prejudice against Western medical men is quite sufficient to induce them, as they certainly did for the first fortnight or three weeks of the existence of the plague, not only to secrete their sick but often to desert their plague-stricken friends and relations after death.

The Governments means of dealing with the crisis was severe. No-one then knew how plague was transmitted. The only certain thing was that it spread rapidly. Insanitary conditions were thought to be the cause, so 7000 people were evicted from their homes. 350 houses were condemned and sealed off and several boatloads of patients were sent to Canton.

The army was sent in to cleanse and disinfect the fetid slums and to collect the dead. The 1st Battalion of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry was stationed in Hong Kong at the time, and when the plague broke out, volunteers were called for to work on plague relief. About 600 of the 1,000 men did so. The unit history tells us that ‘the work was unpleasant in the extreme – searching narrow backstreets and overcrowded houses for plague victims, tending the sick in makeshift isolation hospitals and disinfecting the houses and streets with chloride of lime and whitewash. One of the most unpleasant tasks faced by the volunteers was the location and removal of the dead, searching dark houses and carrying away the bodies to be buried in mass graves. The volunteers of the KSLI lived in quarantine in separate tented camps and were given extra rum rations to help them cope with the work. Remarkably, only one officer and nine men of the regiment fell ill and only two actually died of the plague.(2)

The soldiers found unimaginable horrors. They were on one occasion accompanied by a 28-year-old Scottish doctor, James Lowson, Acting Superintendent of the Civil Hospital. He wrote, ‘On a miserable sodden matting soaked with abominations there were four forms stretched out. One was dead, the tongue black and protruding. The next had the muscular twitchings and semi-comatose condition heralding dissolution. Another sufferer, a female child about ten years old, lay in accumulated filth of apparently two or three days. The fourth was wildly delirious.

The newly completed Kennedy Town Glass Works was requisitioned as a plague hospital. This looks primitive, but was far better than conditions in the slums of Tai Ping Shan.

When the disinfection of houses was undertaken it was the usual practice for the occupants to be issued with new clothes. Their own clothes, bedding, curtains and carpets were sent to a steam disinfecting station. The premises were then thoroughly cleaned by spraying the walls with a solution of perchloride of mercury; alternatively, rooms were fumigated with free chlorine obtained by the addition of diluted sulphuric acid to chlorinated lime. Finally, the floors and furniture were scrubbed with Jeyes fluid, a well-known disinfectant, and the walls were lime-washed. During these operations the occupants were given temporary accommodation on Chinese marriage boats anchored in the harbour off Stonecutters Island.

Other measures taken included the burial of the dead in a plague cemetery at Kennedy Town and the regular disinfecting of all public latrines with chlorinated lime.

The soldiers who carried out these draconian measures were resisted fiercely, and the papers spoke of ‘plague riots. Violent mobs prevented the removal of patients with plague from the Tung Wah Hospital to a special plague hospital, doctors had to carry pistols, and a gunboat was needed to restore order. Placards were posted in Hong Kong and Canton accusing the English doctors of cutting open pregnant women and scooping out the eyes of children in order to make medicines for the treatment of plague victims. Race relations in Hong Kong plunged to a new low; this was a crisis of public health, public order and soon, an economic crisis as well, as ships stopped entering a port that relied on trade for its existence.

Whole blocks of Tai Ping Shan were torn down and rebuilt with proper drainage and better ventilation. This picture was taken in 1898, four years after the plague struck.

The Sanitary Board met often and Lowsons diary reveals that tensions were high. At one meeting, he told two Board members ‘they were both damned cowards as they were afraid to go to the plague areas. He comments ‘Lockhart [the Registrar General] and Governor are now making themselves obnoxious — Bl [bloody] fools. They are walking into the mire properly. His report was later described as ‘an egotistical and garrulous document, written by someone who ‘evidently wants to make a name for himself.

In autumn, the plague subsided, and things calmed down for a time, but for several years it became an almost annual occurrence usually making its appearance in February or March reaching a peak by July and then virtually disappearing during the autumn and winter. Over the period 1894-1901 some 8,600 persons succumbed to the disease and this represented a mortality rate of about 95 per cent of those affected.

During these later years of the plague, house to house searches were made to detect afflicted premises but this also proved difficult. Often, bodies were thrown out at night by the other occupants of infected houses so as to avoid detection and the subsequent disinfection of the premises. In 1900, for example, 412 dead bodies were dumped in the harbour.

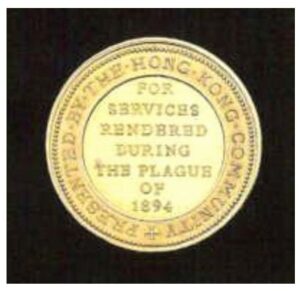

The soldiers of the KSLI earned the gratitude and respect of the Hong Kong government for their work, and a special medal was struck to honour these men who had risked their lives fighting an unseen and very terrible enemy.(3)

'An Unexampled Calamity'

A peste de Hong Kong de 1894

Stuart Braga

Artigo publicado originalmente em Casa de Macau Austrália Bulletin

“Sem exagero, posso afirmar que, no que diz respeito ao comércio e ao comércio, a praga assumiu a importância de uma calamidade sem precedentes. Assim, afirmou o envio do governador de Hong Kong, Sir William Robinson, ao Secretário de Estado das Colônias em Londres em 20 de junho de 1894. “(1)

Ele quis dizer que não havia outro exemplo de tão grande calamidade. A calamidade foi um grave surto de peste bubônica, que deixou Hong Kong de joelhos. Estranhamente, embora também tenha devastado o cantão, deixou Macau praticamente intacta. Sir William poderia ter acrescentado que era uma vasta tragédia humana também, pois vários milhares de pessoas, a maioria pobres chinesas, morreram e mais de 100.000 fugiram em pânico para suas aldeias de origem.

Um oficial da Kings Shropshire Light Infantry supervisiona as tropas limpando as ruas em Tai Ping Shan

Parece que antes da doença chegar a Hong Kong, ela havia eclodido em Canton em janeiro daquele ano, e em junho havia sido responsável por cerca de 80.000 mortes. Rapidamente se movendo para baixo, ele apareceu pela primeira vez no distrito de Tai Ping Shan nos primeiros meses de 1894. Naquela época, Tai Ping Shan, bem acima da cidade de Kennedy, a oeste do distrito central de Hong Kong, era um assentamento lotado de trabalhadores chineses. Não havia abastecimento de água ou saneamento, e as condições de vida eram totalmente sujas.

Em Tai Ping Shan houve pânico e histeria, pois o resultado na grande maioria dos casos foi uma morte agonizante após três dias de sofrimento. Uma descrição gráfica dos sintomas da peste bubônica foi dada por M. Wilm em seu Relatório de Praga em Hong Kong compilado em 1896. O Wilm observou que

No início da doença, a língua geralmente ficava inchada, vermelha brilhante na ponta e nas bordas e estava coberta com uma pele branca acinzenta. Normalmente, no segundo ou terceiro dia da doença, a pele ficou acastanhada ou preta e seca em uma crosta. A língua fica rachada e fissurada … Os lábios logo se tornaram secos e muitas vezes fissurados, a membrana mucosa da boca e a faringe geralmente era vermelha brilhante. E o apetite desapareceu. Houve frequentemente vômitos incontroláveis e grande sede.”

Ele continua, mas os detalhes são muito angustiantes para se relacionar aqui.

Soldados da King’s Shropshire Light Infantry supervisionam a remoção de um caixão de uma vítima da peste, carregado em um poste por coolies.

Em 10 de maio de 1894 Hong Kong foi declarada um porto infectado e, no espaço de algumas semanas, o governo foi confrontado com uma epidemia de grande magnitude. Em julho, houve 2442 mortes. Os hospitais foram rapidamente estabelecidos a bordo do navio de guerra, Hygeia, na Delegacia de Polícia da Cidade Kennedy e nas obras de vidro da Cidade Kennedy. Os dois primeiros foram administrados por funcionários europeus, enquanto o terceiro foi tripulado pelo pessoal chinês do hospital Tung Wah. O governador disse ao seu superior em Londres que “foi considerado aconselhável dar aos médicos chineses uma mão livre no início. Em qualquer caso, é difícil persuadir os chineses a relatar casos de doença e seu preconceito tolo e violento contra os médicos ocidentais é suficiente para induzi-los, como eles certamente fizeram durante a primeira quinzena ou três semanas da existência da praga, não só para secretar seus doentes, mas muitas vezes para abandonar seus amigos e parentes atingidos pela peste após a morte.

Os meios do governo para lidar com a crise eram graves. Ninguém sabia como a peste era transmitida. A única coisa certa foi que se espalhou rapidamente. Acreditava-se que as condições insalubres eram a causa, de modo que 7000 pessoas foram despejadas de suas casas. 350 casas foram condenadas e seladas e vários barcos carregados de pacientes foram enviados para Canton.

O exército foi enviado para limpar e desinfetar as favelas fétidas e coletar os mortos. O 1o Batalhão da Infantaria Ligeira de Shropshire do Rei estava estacionado em Hong Kong na época, e quando a praga eclodiu, voluntários foram chamados para trabalhar no alívio da peste. Cerca de 600 dos mil homens o fizeram. A história da unidade nos diz que “o trabalho foi desagradável ao extremo – procurando ruas estreitas e casas superlotadas para vítimas da peste, cuidando dos doentes em hospitais de isolamento improvisados e desinfetando as casas e ruas com cloreto de cal e branqueamento. Uma das tarefas mais desagradáveis enfrentadas pelos voluntários foi o local e a remoção dos mortos, procurando casas escuras e transportando os corpos para serem enterrados em valas comuns. Os voluntários da KSLI viviam em quarentena em acampamentos de tendas separados e recebiam rações extras de rum para ajudá-los a lidar com o trabalho. Notavelmente, apenas um oficial e nove homens do regimento adoeceram e apenas dois realmente morreram da praga.(2)

Os soldados encontraram horrores inimagináveis. Eles foram em uma ocasião acompanhados por um médico escocês de 28 anos, James Lowson, superintendente interino do Hospital Civil. Ele escreveu: “Em um miserável enlouquecimento encharcado de abominações, havia quatro formas estendidas. Um estava morto, a língua negra e saliente. O próximo teve os espasmos musculares e a condição semi-comatosa de isolar a dissolução. Outro sofredor, uma criança do sexo feminino, estava deitado em sujeira acumulada de aparentemente dois ou três dias. O quarto foi descontroladamente delirante.

A recém-concluída Kennedy Town Glass Works foi requisitada como um hospital de peste. Isso parece primitivo, mas era muito melhor do que as condições nas favelas de Tai Ping Shan.

Quando a desinfecção das casas foi realizada, era a prática usual para os ocupantes receberem roupas novas. Suas próprias roupas, roupas de cama, cortinas e tapetes foram enviados para uma estação de desinfecção a vapor. As instalações foram então cuidadosamente limpas pulverizando as paredes com uma solução de percloreto de mercúrio; alternativamente, as salas foram fumigadas com cloro livre obtido pela adição de ácido sulfúrico diluído ao cal clorado. Finalmente, os pisos e móveis foram lavados com fluido Jeyes, um desinfetante bem conhecido, e as paredes foram lavadas com cal. Durante essas operações, os ocupantes receberam alojamento temporário em barcos de casamento chineses ancorados no porto da Ilha Stonecutters.

Outras medidas tomadas incluem o enterro dos mortos em um cemitério de peste na cidade de Kennedy e a desinfecção regular de todas as latrinas públicas com cal clorada.

Os soldados que realizaram essas medidas draconianas foram resistidos ferozmente, e os jornais falaram de “motins de pragas”. Mobs violentos impediram a remoção de pacientes com peste do Hospital Tung Wah para um hospital especial da peste, os médicos tiveram que carregar pistolas e uma canhoneira era necessária para restaurar a ordem. Placas foram postadas em Hong Kong e Canton acusando os médicos ingleses de cortar mulheres grávidas abertas e tirar os olhos das crianças, a fim de fazer medicamentos para o tratamento das vítimas da peste. As relações raciais em Hong Kong caíram para uma nova baixa; esta foi uma crise de saúde pública, ordem pública e, em breve, uma crise econômica também, à medida que os navios pararam de entrar em um porto que dependia do comércio para sua existência.

No centro dos eventos durante a epidemia de Hong Kong estava o Dr. Lowson. Uma cópia de seu diário está no Museu de Ciências Médicas de Hong Kong.(2) As entradas escritas apressadamente contam uma história terrível, tanto do sofrimento quanto da falta de comunicação entre médicos ocidentais e chineses. Em 10 de maio, no Hospital Tung Wah, Lowson “encontrou aproximadamente 20 pessoas deitadas ali afetadas com a peste – tudo em estágio avançado da doença. A maioria veio de Tai Ping Shan. O hospital usou apenas a medicina tradicional chinesa e foi responsabilizado por Lowson por não diagnosticar casos de peste mais cedo. “Não posso denunciar este foco de vício médico e sanitário em termos suficientemente fortes… uma vergonha e perigo para a saúde pública de Hong Kong.

Blocos inteiros de Tai Ping Shan foram demolidos e reconstruídos com drenagem adequada e melhor ventilação. Esta foto foi tirada em 1898, quatro anos após a peste ter atingido.

O Conselho Sanitário se reuniu com frequência e o diário de Lowsons revela que as tensões eram altas. Em uma reunião, ele disse a dois membros do Conselho que “eles eram ambos malditos covardes, pois tinham medo de ir para as áreas da praga. Ele comenta: “Lockhart [o secretário-geral] e o governador agora estão se tornando desagradáveis – b) tolos. Eles estão caminhando para a lama corretamente. Seu relatório foi mais tarde descrito como “um documento egoísta e grosseiro, escrito por alguém que “evidentemente quer fazer um nome para si mesmo”.

No outono, a praga diminuiu e as coisas se acalmaram por um tempo, mas por vários anos tornou-se uma ocorrência quase anual geralmente fazendo sua aparição em fevereiro ou março atingindo um pico em julho e depois praticamente desaparecendo durante o outono e inverno. No período de 1894-1901 cerca de 8.600 pessoas sucumbiram à doença e isso representou uma taxa de mortalidade de cerca de 95% das pessoas afetadas.

Durante esses últimos anos da praga, buscas de casa em casa foram feitas para detectar instalações afligidas, mas isso também se mostrou difícil. Muitas vezes, os corpos eram jogados fora à noite pelos outros ocupantes de casas infectadas, de modo a evitar a detecção e a subsequente desinfecção das instalações. Em 1900, por exemplo, 412 corpos foram despejados no porto.

Os soldados da KSLI ganharam a gratidão e o respeito do governo de Hong Kong por seu trabalho, e uma medalha especial foi tomada para homenagear esses homens que arriscaram suas vidas lutando contra um inimigo invisível e muito terrível.(3)