Dr Eduardo Liberato “Eddie” Gosano 1914-2010

Feature Story from Club Lusitano, Hong Kong, 18/06/2021

Extracts from his extraordinary, and colourful autobiography, “Hong Kong Farewell”, by Eddie Gosano, (1997), after he migrated to the USA. A full copy is available in the Club Lusitano Biblioteca.

This is enough insight of my ancestry to give you a particular insight into Portuguese, as well as other Western European culture of those times. Major Gosano came from landed gentry in Togal, Portugal. It was the custom for the first born son to be the heir of the estate. The second son was to be a soldier. So fated, Grandfather Leonardo Jose Gosano was destined to end his days and leave his progeny in the Far East colony of Macao.

My mother’s maiden name was Adeliza Maria Marques. Her father was a Goan of Indian origin with a trace of Portuguese. Her mother Antonia Luz, was a Portuguese with probably one-fourth Chinese ancestry.

The Gosanos

I was born in Hong Kong, an island at the bottom of China. I lived there for 44 years. How that rocky speck of land, overshadowed by Communist China became the third mightiest financial center in the capitalistic world defies logic. I know. I was part of the administration that made it what it is.

My father Julio dos Passos Gosano, was the second son (and this is significant) of Leonardo Jose Gosano, a lieutenant in the Portuguese Colonial Army. Grandfather Gosano in the 1800s was based on the Portuguese island colony of Timor. He was later seconded to Macao to serve in the military constabulary as lieutenant and in time be promoted to captain. He retired as major on 12 November 1891 in Macao. Thirteen years later on, 11 November 1904, he died.

This is enough insight of my ancestry to give you a particular insight into Portuguese, as well as other Western European culture of those times. Major Gosano came from landed gentry in Togal, Portugal. It was the custom for the first born son to be the heir of the estate. The second son was to be a soldier. So fated, Grandfather Leonardo Jose Gosano was destined to end his days and leave his progeny in the Far East colony of Macao.

My mother’s maiden name was Adeliza Maria Marques. Her father was a Goan of Indian origin with a trace of Portuguese. Her mother Antonia Luz, was a Portuguese with probably one-fourth Chinese ancestry.

Look not in dismay, I beg of you, at this medley of European and Far Eastern identities. Exotic Macao and HK defy comparison with America’s melting pot. Our racial commingling is more recent and due to the consequence of mortal earthquakes amid the never ending upheavals of human society surrounding our part of the world. We are left trying to preserve a sensitivity to our ancestry of which we are proud, especially we Portuguese.

When she was married to my father, mother was 17. Like clock works every 2 years a new addition was made to the family. By the time she was 25 there were 5 children including me. This was on course for a virile Portuguese husband, a Catholic, where birth control came only from breast feeding and possibly abstinence.

Being such a tiny colony, Macao afforded limited openings for a livelihood, which is why my father migrated to HK where I was born. He found a position as bank clerk in the HK & Shanghai Bank. Gifted with a beautiful handwriting, he was soon assigned the important responsibility to record all new accounts.

This bank was and still is situated in the centre of Victoria, the capital of HK, on Queen’s Road Central.

Discrimination, British Style

Lowering the historical curtain to this point, let me add that the HK & Shanghai Bank where my father was noted for his handsome penmanship, was immediately across the tram lines, an arm’s throw from the most prestigious English clubs, the HK Club and the HK Cricket Club. My father because of his non-British nationality, was not a member of either club. The wily British, fore-stalling the possibility that hordes of colonist refugees might someday invade their shores, to claim their rights as citizens, never granted them citizenship. All those not of British extraction in HK came under the legal designation as Chinese (who comprised 95% of the population). While we Portuguese were independent citizens of our native land, for all practical and legal purposes in HK we were Chinese.

The discrimination hurt most in the economic exploitation. My father, for instance, after 20 years service with the bank, was being paid a monthly wage of $300 HK, the equivalent of US$50.

By that time there were 9 children in our family. My 2 oldest brothers, Adelino Vitus and Bellarmino Tomas, were working as clerks. My third brother, Carlos Noberto (nicknamed Carlinho) left school early and was working at the same bank. By the time I was 8 years old I was attending school on my own, three or four miles from home.

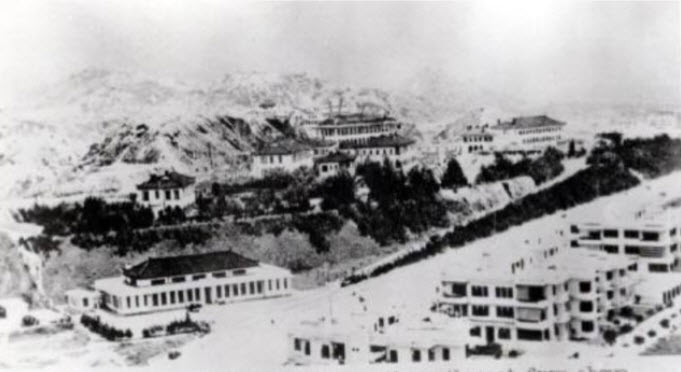

St Joseph’s school was run by a Catholic order of Christian brothers. It was situated a third of the way up the Victoria Peak, and was approachable by tram car.

I was on the electric tram, returning home from school, when, as another tram was crossing on another track, a relative spotted me and shouted the news. My father Julio dos Passos Gosano, age 40, had just drowned in HK Harbour. That year was 1923.

One Flat, for 18 of us

My father left his family a provident fund of $15,000 (HK). Thanks to some questionable good influences, including two of my mother’s brothers, this money was quickly gambled away in the stock exchange.

Adelino Vitus – Lino as he was called, being the eldest, became the father of our family and guided our destinies as best he could. But words are beyond my reach to convey the courage of Lino and my mother. We were living a flat in Tin Lock Lane on waterfront at the entrance to Happy Valley in HK. Not only did my mother have to oversee us 9 Gosanos, there were with us in the same flat her 2 younger bachelor brothers, Jose and Luiz Zeferino Marques. Then there were 4 orphaned cousins Mano, Atina, Alita, and Natercia Rodrigues. All 18 of us lived in that flat.

How did my mother manage? First, every one of age worked. All were required to share their wages. And through living a very modest way of life, my mother managed to rear all of us until everyone was able to go on our own.

The plight of the Gosanos was little different than that of the vast majority of HK. For all its expansion there has never been adequate housing. Kowloon, from the misty past, has always been overspilling with impoverished families.

Medical School

When I was about 13 years old Lino asked me, “What preference would you have for your future education?”

Being impressed with our family doctor, Dr Ozorio, in one of his visits to render aid to one of the family, I replied that I would like to be a doctor. Lino was then Secretary to the Registrar of HK University. His work entailed all of the secretarial details of the operation of the University. That included the local matriculating school examinations for admittance. At the end of the year 1929, I matriculated from St Joseph’s College, qualified scholastically to enter the University of HK as a medical student.

At that time I was only 15 years old; that’s was 2 years short of the requirement for entering the medical college. But as I said, Adelino Vitus Gosano was Secretary to the Registrar. He did not look too closely at my birth certificate. In 1930, only 10 days after my 15th birthday, I was probably the youngest person enrolled in the University of HK. I was given a Sir Paul Chater Memorial Scholarship plus a scholarship from Socorro Mutos, a local Portuguese Society that contributed to needy students. This paid my tuition. Even though we were limited in our financial resources, my mother managed to supply me with the means to round out my extra needs. I resided at the newly opened Ricci Hall, a Jesuit hostel, for all of the 7 years of my studies at the University.

Earns $8 a month

My degree was conferred in January 1937. Not long after that I was able to obtain the post of Houseman (Intern in the US vernacular) to Professor K.H Digby, Professor of Surgery in the Faculty of Medicine at the University. I was anaesthetist for all surgery for the benefit of medical students. Three times a week on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, from 7am to well into the afternoons, surgery took place. … Let me tell you a bit about how anaesthesia was administered in HK in 1937. It was given on a mouth mask covered with gauze. Ether or chloroform was applied in drops until the patient went under. A heavy towel was placed over the mask to keep the amount of anaesthetic to the minimum. Meanwhile the anaesthetist was inhaling almost as much ether or chloroform as all of the patients combined for the day.

My post as surgical Houseman kept me in the hospital 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year 1937. The stipend of $50(HK), equivalent to $8 US, monthly. After my first five months the entire hospital was transferred to a new 600-bed facility the Queen Mary Hospital. Following my 1st year as houseman in the University surgical unit, I was offered a position in the Medical Department of the HK Government in Kowloon…the work was the same. But the salary jumped to the fabulous amount of $200(HK) a month or about $35 US.

.

On 1 January 1939, at the age of 24 I was appointed Surgical Medical Officer of the Medical Department of HK in Kowloon Hospital. But mind you there were strings attached. While of Portuguese ancestry and status as recognised in my native country, here in the British colony, I was still legally classified as Chinese. My compeer was Dr G.A.V. Griffith, a Britisher of 45 or 50 years of age. The two of us performed all surgery for this Government Civil Hospital. Our workload was measured in terms of free services, for 100,000 people, 24 hours a day.

Japan Invades HK, I volunteer for Prisoner of War Camps

Emergency plans had been made in advance. At such time I was to call my senior surgical officer, Dr. Issac Newton. He assigned me back to Kowloon hospital, which was close to Kai Tak Airport. The Airport was the main target of the Japanese air force. Casualties were streaming into the emergency centres in Kowloon.

From Monday through Thursday we worked like dogs on casualties without number. Then the Japanese over-ran Kowloon. All work ended. There was no gas, no electricity, no more sterilized equipment for surgery. We at Kowloon Hospital were simply isolated. No more ambulances were running. No cases coming in.

On Thursday morning 12 December a lone Japanese soldier with a rifle came up the drive of the Hospital. About 150 yards behind came a sergeant with a sword and revolver. The two of them took over the hospital without resistance.

On the 11th day of our captivity we were taken to the Kowloon Hotel at the tip of the peninsula… We were not fully settled into the hotel when we had a visitor. He was a senior medical officer of the Japanese Army. His name was Major Konishi. He had a problem. British wounded prisoners-of-war were being kept at a camp on Argyle Street. The war was still raging in HK. Japanese casualties like our own, were heavy. The Japs were strapped for medical personal for their own needs. Would some of us volunteer to serve our own casualties on Argyle Street?

The three senior medical officers were of British origin. They of course volunteered to care for their own. I was ranked as a junior medical officer because of my Chinese status. Just the same Dr. Newton said, “Eddie, you come too, you have to help me.”

I didn’t have to “come too”. There was a way out for me. A way that meant freedom in Macao. Macao was a Portuguese colony only 40 miles away and Portugal was not at war with Japan. In fact the Governor of Macao at that time was issuing an invitation to HK doctors of Portuguese origin but with British degrees to practice freely in Macao. But my senior medical officer had accorded me equal dignity in the profession and now he needed me. And who, more than casualties of the war, needed our services more? It was instilled in our family to serve where there was need. I volunteered. …

Try to picture this camp through a physician’s eyes: a few dozen zinc huts housing 20 to 30 persons each. No beds. Patients and doctors alike slept on planks propped above ground level My job was the dirty work of cleaning and dressing wounds. There were so many wounded it took long hours each day…

It is not easy to describe the circumstances in such prison camps. Before the war I had been an outstanding athlete in HK. My weight when entering the camp, was a fighting 155 pounds. It came down to 130 pounds on the starvation diet. The wounded prisoners, despite their injuries, were given no better fare. Besides this, there was always the mortal fear, hanging over us like the sword of Damocles, of committing some infraction. One and all knew the treatment meted out to offenders of the Japanese Army. The penalty for any transgression of the purported code of the Japanese Occupation, was death by beheading in the street.

Grotesque: A prisoner of war, about to be beheaded by a Japanese

Stranded Among the Prisoners

Now at Argyle Street, Dr Newton had made use of his position as surgeon to get out of prison and reside in a civilian hospital called St. Theresa’s Hospital on Prince Edward Road. Dr Uttley had a bout with dysentery and was treated at St Theresa’s and then sent to the civilian prison camp at Stanley in HK.

This left Dr. Hargreaves and me stranded like surplus baggage in the prisoner-of-war camp at Argyle Street. Then they transferred us to the Sham Shui Po Camp, a prison camp for other ranks or OR’s, from all the forces – British, Canadian, Indian, Eurasian, Portuguese – that had fought for HK.

There were almost 200 Macanese (Portuguese) in these prison camps. Among them, besides myself, were my three younger brothers, Luigi, Jerry and Zinho who had all volunteered for the defense of HK. Zinho was sent to Japan to work in their coal mines and was kept until liberated by American soldiers after Japan surrendered.

Dr. Hargreaves and I languished at Sham Shui Po for months despite our pleas to the Japanese commandant that we were civilian medical personnel. We were in prisoner of war camps in the first place because we had volunteered when Major Konishi, the Japanese medical officer, asked for our help. With the war ended and the Royal Army Medical Corps once more available, why were we left stranded like excess baggage for 7 months with no fruitful work in a military prison camp?

We Migrate to Macau

In June 1942 Dr Gosano was allowed to leave the POW camp and return to his family. Shortly thereafter he was invited by fellow Portuguese Dr HLP Ozorio to work in the British Consulate in Macao.

In June 1942 there were 3 doctors of Portuguese origin from HK practicing in Macao. There were Drs. Ozorio, G.A.V. Ribeiro and J.W. Barnes. I was, on arriving in Macao, immediately given the same privileges as they.

We had our own medical offices and billed the British Consulate for services rendered. However, the number of refugees from HK became so great that it was becoming a financial impossibility for the British Consulate to keep up. So we 4 doctors agreed to be paid at staff wages. Our staff were on call 24 hours a day with at least one doctor on call night and day at the out patient clinic. House visits were made where necessary. We were not allowed to see or treat patients in the Macao Govt. hospitals and had no privileges for surgery.

Soon after arriving I was privileged to become the attending physician to the British Consul, Mr J.P. Reeves. His daughter was Leticia, called Tecia. Tecia had chronic and recurring asthma. This entailed almost daily visits in the evenings as her bouts of acute asthma usually came at sunset. I became a family friend and was constantly in their house in the evenings for meals and also a game of Mah Jong with his wife Rhonda and his office secretary, a Portuguese girl named Micas Gonsalves and the Consul himself.

Heading up the Secret Service

Also I became physician to an English lady named Joy Wilson. Her husband, Geoffrey, was a police commissioner of the HK Police. And there was another English lady, Mrs E.J.R. Mitchell, in Macao.

In the spring of 1943 the two women, along with the European manager of the Macao Electric company, decided to leave Macao and try to get through the Japanese lines to the headquarters of the Allied forces in Kun Ming, China.

Then came an astonishing event. I would not have been surprised had her husband the Police Commissioner been head of the British secret service. But then Mrs Joy Wilson confided in me that she was the head of the BAAG, the British Army Aid Group. “You are the one person I feel I can trust, Dr Gosano”, she said.

Incredible as it sounded, she asked me to take her position as head of the underground BAAG in Macao.

There was not a more suicidal state to be caught in while still alive, no matter what your nationality or where you were caught. The Japanese had their counter underground too. And there was always that testy question of Portuguese neutrality – what incident might provoke hostilities and Portugal would find herself involved in the War?

For one thing the BAAG was tied in with some river pirates, three brothers named Wang. They were depended on to transport people through the Japanese lines around Macao to allied headquarters in Kun Ming (Kunming), China.

Joy Wilson was leaving 3 Chinese associates in the Macao BAAG. They were Y.C. Liang (known as P.L.), Fung Bay and N.K. Mar. Liang was a rice merchant with a small shop in the center of Macao near St Domingo Church. He became a rich and prominent financier after the war. Fung Bay became his right hand man, and still works for the Liang family in HK.

The Commandant of the BAAG was Lieutenant Colonel L.T. Ride. Ride had been a professor of Physiology at the University of HK. When war came he was in the Royal HK Defence Force. He was interned with all of the volunteers of the RHKDF at Shum Shui Po prisoner of war camp. But almost immediately his personal Chinese secretary came to the sea wall in a junk and Professor Ride was able to escape over the wall. The two of them made their way to Kunming, China. There Ride organized the BAAG with himself as Commandant.

I had known him from my cricketing days at the University of HK. During 1935 and 36 I was captain of the student team that played the faculty in what was called the annual Phoenix Match. Now in our new association in the BAAG, each of us had a code name. I am sure Lt. Col. Ride was recalling those cricketing days when he gave me the code name Phoenix.

Being a practising physician made my friendship with the British Consul quite plausible and my medical clinic was the perfect cover for British agents visiting Macao. The function of the BAAG in Macao was to correlate any information that could be important to the British Army. We were also helpful to personnel needs of the Allies. There was the time when 3 American aviators were shot down around Canton, China. One was a fighter pilot and the other two were pilot and gunner on a torpedo plane carrier. They were picked up by fishermen and taken into Macao to the British Consul. The river pirates and of our group took the 3 to China.

At any point along this chain of intrigue, had the Japanese detected the rescue, heads would have fallen and possibly an altercation between Portugal and Japan could have occurred. I lived in a constant stage of apprehension, wondering why I had agreed to relieve Mrs Joy Wilson. Being an undercover agent working against a deadly and crafty enemy was no imaginary danger. It was real. I carried a small pistol for the years of my work with the BAAG. Despite the abiding dread of execution I remained with the others in the secret service until Japan surrendered and the occupation ceased.

Escape of Leo d’Almada

The Honorable Leo d’Almada was the leading representative of the Portuguese community in HK. Mr. d’Almada was a QC (Member of the Queens’s Council), as well as a member of the Executive Council of the HK Government. He was housed in a pavilion on the tennis court of the Governor of Macao.

The British Consul received a message from the British Government. The Consul was to tell d’Almada that the Government wanted him in England to take part in organizing a task force prepared for retaking and rehabilitating HK when Japan would eventually be defeated. Mr d’Almada well knew the dangers of trying to escape to England through the Japanese network. He declined the summon.

The British Government requested me through the BAAG to see Mr. d’Almada. As we were acquainted socially, I could address him personally. “Leo” I said, “as head of the BAAG in Macao, I know of this message from England. As the senior Portuguese in HK, it is very important to us Portuguese, as well as British subjects, for you to go to England. Our organization will get you safely to Kunming and then to London.”

His obligation must have been weighing on his conscience. He did not take affront at my boldness. What worried him was the thought of leaving his wife in such precarious abandonment should he be caught. “Could Tilly come too?” he asked ” I am not sure” I said. “I will ask Y.C. Liang. He will be directly involved.”

Leo and Tilly d’Almada were delivered safely through the perils by our underground agents. Mr d’Almada would return to HK one day, prepared for the provisional takeover Government.

Epilogue

Immediately after the war (on 26 November 1945), Dr Gosano married Hazel Lang, a Eurasian girl who had been his neighbour in Kowloon, at St Theresa’s church. They had 3 daughters Stephanie, Susanne and Edwina.

Dr Gosano returned to Kowloon Hospital after the war as a “Chinese medical officer”. He was then assigned to Queen Mary Hospital for general and ear, nose and throat surgery. Despite his heroic efforts during the war and for his perilous work for the BAAG, he was subjected to continued colonial discrimination in the service of the HK government.

It was only with the intervention of his follow BAAG comrade, Major Bevan Field of the HK Investment Company (HK Land) and the HK Volunteers, was he eventually able to set up private practice in Edinburgh House 14 years after his graduation.

In 1950 he was invited to serve as member of the Urban Council, representing the Portuguese interests in HK, replacing Dr A.M. Rodrigues. He served in this capacity for the next 10 years particularly on select committees concerning public health. In his own words “This service was without any kind of remuneration save for the appreciation of the people we served”.

1953: Lelaine Mok, Gordon Randall, Tracy Brown, Hazel and Dr Eddie Gosano

Dr Gosano also continued his service as a medical officer with the HK Regiment of the Defense Force volunteering in 1949 with the rank of Captain. He rose to senior medical officer of the HK regiment with the rank of Major in 1955.

He migrated to the United States in 1960, securing a position as an intern at St Joseph’s Hospital, San Francisco. At the time HK medical qualifications were not recognised there and he was required to serve 3 years as a mature age 46 year old intern to complete his MD degree in the USA.

He died in San Francisco aged 96.

Dr Eduardo Liberato “Eddie” Gosano 1914-2010

História do Club Lusitano, Hong Kong, 18/06/2021

Extratos de sua extraordinária e colorida autobiografia, “Hong Kong Adeus”, de Eddie Gosano (1997), depois que ele migrou para os EUA. Está disponível uma Cópia completa no Clube Lusitano Biblioteca.

Esta é uma visão suficiente da minha ascendência para lhe dar uma visão particular do português, bem como de outra cultura da Europa Ocidental daqueles tempos. O major Gosano veio de terras desembarcadas em Togal, Portugal. Era costume para o filho primogênito ser o herdeiro da propriedade. O segundo filho era ser um soldado. Tão pendente, o avô Leonardo José Gosano estava destinado a terminar os seus dias e deixar a sua progênie na colónia do Extremo Oriente de Macau.

O nome de solteira da minha mãe era Adeliza Maria Marques. Seu pai era um goma de origem indiana com um traço de português. Sua mãe Antonia Luz, era um português com provavelmente um quarto de ascendência chinesa.

Os Gosanos

Eu nasci em Hong Kong, uma ilha no fundo da China. Eu moro lá por 44 anos. Como esse pedaço de terra rochoso, ofuscado pela China comunista, tornou-se o terceiro centro financeiro mais poderoso do mundo capitalista desafia a lógica. Eu sei. Eu sei. Eu fazia parte da administração que fez o que é.

Meu pai Julio dos Passos Gosano, foi o segundo filho (e isso é significativo) de Leonardo José Gosano, tenente do Exército Colonial Português. O avô Gosano em 1800 foi baseado na colônia insular portuguesa de Timor. Mais tarde, foi destacado para Macau para servir na polícia militar como tenente e a tempo ser promovido a capitão. Aposentou-se como major em 12 de novembro de 1891 em Macau. Treze anos depois, em 11 de novembro de 1904, ele morreu.

Esta é uma visão suficiente da minha ascendência para lhe dar uma visão particular do português, bem como de outra cultura da Europa Ocidental daqueles tempos. O major Gosano veio de terras desembarcadas em Togal, Portugal. Era costume para o filho primogênito ser o herdeiro da propriedade. O segundo filho era ser um soldado. Tão pendente, o avô Leonardo José Gosano estava destinado a terminar os seus dias e deixar a sua progênie na colónia do Extremo Oriente de Macau.

O nome de solteira da minha mãe era Adeliza Maria Marques. Seu pai era um goma de origem indiana com um traço de português. Sua mãe Antonia Luz, era um português com provavelmente um quarto de ascendência chinesa.

Não vos deixeis desanimar, peço-vos, para esta mistura de identidades europeias e do Extremo Oriente. Macau e HK exóticos desafiam a comparação com o caldeirão da América. Nossa mistura racial é mais recente e devido à consequência de terremotos mortais em meio às convulsões intermináveis da sociedade humana em torno de nossa parte do mundo. Somos deixados tentando preservar uma sensibilidade à nossa ancestralidade da qual estamos orgulhosos, especialmente nós portugueses.

Quando ela era casada com meu pai, minha mãe tinha 17 anos. Como o relógio funciona a cada 2 anos, uma nova adição foi feita à família. Quando ela tinha 25 anos, havia 5 crianças, incluindo eu. Isso estava em curso para um marido português viril, um católico, onde o controle de natalidade veio apenas da amamentação e, possivelmente, da abstinência.

Sendo uma colónia tão pequena, Macau proporcionou aberturas limitadas para um meio de subsistência, razão pela qual o meu pai migrou para HK onde eu nasci. Ele encontrou uma posição como balconista bancário no HK & Shanghai Bank. Dotado de uma bela caligrafia, ele logo recebeu a importante responsabilidade de gravar todas as novas contas.

Este banco estava e ainda está situado no centro de Victoria, a capital de HK, na Queen’s Road Central.

Look not in dismay, I beg of you, at this medley of European and Far Eastern identities. Exotic Macao and HK defy comparison with America’s melting pot. Our racial commingling is more recent and due to the consequence of mortal earthquakes amid the never ending upheavals of human society surrounding our part of the world. We are left trying to preserve a sensitivity to our ancestry of which we are proud, especially we Portuguese.

When she was married to my father, mother was 17. Like clock works every 2 years a new addition was made to the family. By the time she was 25 there were 5 children including me. This was on course for a virile Portuguese husband, a Catholic, where birth control came only from breast feeding and possibly abstinence.

Being such a tiny colony, Macao afforded limited openings for a livelihood, which is why my father migrated to HK where I was born. He found a position as bank clerk in the HK & Shanghai Bank. Gifted with a beautiful handwriting, he was soon assigned the important responsibility to record all new accounts.

This bank was and still is situated in the centre of Victoria, the capital of HK, on Queen’s Road Central.

Discriminação, Estilo Britânico

Baixando a cortina histórica até este ponto, deixe-me acrescentar que o HK & Shanghai Bank, onde meu pai era conhecido por sua bela caligrafia, estava imediatamente do outro lado das linhas de bonde, um arremesso de braço dos clubes ingleses mais prestigiados, o HK Club e o HK Cricket Club. Meu pai por causa de sua nacionalidade não-britânica, não era um membro de nenhum dos clubes. Os astutos britânicos, presidam a possibilidade de que hordas de refugiados colonizadores possam um dia invadir suas costas, reivindicar seus direitos como cidadãos, nunca lhes concederam cidadania. Todos aqueles que não eram de extração britânica em HK ficaram sob a designação legal como chineses (que compunham 95% da população). Enquanto nós, portugueses, éramos cidadãos independentes da nossa terra natal, para todos os fins práticos e legais em HK, éramos chineses.

A discriminação mais prejudica a exploração econômica. Meu pai, por exemplo, depois de 20 anos de serviço com o banco, estava recebendo um salário mensal de US $ 300 HK, o equivalente a US $ 50.

Naquela época, havia nove crianças em nossa família. Meus dois irmãos mais velhos, Adelino Vitus e Bellarmino Tomas, estavam trabalhando como balconistas. Meu terceiro irmão, Carlos Noberto (apelidado de Carlinho) deixou a escola cedo e estava trabalhando no mesmo banco. Quando eu tinha 8 anos, eu estava frequentando a escola sozinha, a três ou quatro milhas de casa.

A escola de São José era administrada por uma ordem católica de irmãos cristãos. Ele estava situado um terço do caminho até o Victoria Peak, e era acessível por carro de bonde.

Eu estava no bonde elétrico, voltando para casa da escola, quando, enquanto outro bonde estava atravessando outra pista, um parente me avistou e gritou a notícia. Meu pai, Julio dos Passos Gosano, de 40 anos, tinha acabado de se afogar em HK Harbour. Esse ano foi 1923.

Um apartamento, para 18 de nós

Meu pai deixou a família um fundo de previdência de US $ 15.000 (HK). Graças a algumas boas influências questionáveis, incluindo dois dos irmãos da minha mãe, esse dinheiro foi rapidamente apostado na bolsa de valores.

Adelino Vitus – Lino como ele era chamado, sendo o mais velho, tornou-se o pai da nossa família e guiou nossos destinos da melhor maneira que podia. Mas as palavras estão além do meu alcance para transmitir a coragem de Lino e da minha mãe. Estávamos vivendo um apartamento em Tin Lock Lane na orla na entrada para Happy Valley em HK. Não só minha mãe teve que nos supervisionar 9 Gosanos, havia conosco no mesmo apartamento seus 2 irmãos solteiros mais novos, José e Luiz Zeferino Marques. Depois, havia quatro primos órfãos Mano, Atina, Alita e Natercia Rodrigues. Todos os 18 de nós viviam naquele apartamento.

Como é que a minha mãe conseguiu? Primeiro, cada um dos anos de idade funcionou. Todos eram obrigados a dividir seus salários. E ao viver um modo de vida muito modesto, minha mãe conseguiu nos criar até que todos pudessem ir por conta própria.

A situação dos Gosanos era pouco diferente da da grande maioria de HK. Apesar de toda a sua expansão, nunca houve habitação adequada. Kowloon, do passado enevoado, sempre foi sobrespista com famílias empobrecidas.

Faculdade de Medicina

Quando eu tinha cerca de 13 anos, Lino me perguntou: “Que preferência você teria para sua educação futura?”

Ficando impressionado com o nosso médico de família, Dr. Ozorio, em uma de suas visitas para prestar ajuda a uma da família, eu respondi que eu gostaria de ser um médico. Lino foi então secretário do secretário da Universidade de Hong Kong. Seu trabalho envolveu todos os detalhes do secretariado da operação da Universidade. Isso incluiu os exames escolares locais para admissão. No final do ano de 1929, matriculei-me do St Joseph’s College, qualifiquei-me escolasticamente para entrar na Universidade de Hong Kong como estudante de medicina.

Naquela época eu tinha apenas 15 anos; isso era 2 anos antes da exigência de entrar na faculdade de medicina. Mas, como eu disse, Adelino Vitus Gosano foi secretário do secretário. Ele não olhou muito de perto para a minha certidão de nascimento. Em 1930, apenas 10 dias após o meu 15o aniversário, eu era provavelmente a pessoa mais jovem matriculada na Universidade de Hong Kong. Foi-me dada uma Bolsa Sir Paul Chater Memorial mais uma bolsa de estudos da Socorro Mutos, uma Sociedade Portuguesa local que contribuiu para estudantes necessitados. Isto pagou a minha taxa de matrícula. Mesmo que fôssemos limitados em nossos recursos financeiros, minha mãe conseguiu me fornecer os meios para completar minhas necessidades extras. Eu residi no recém-inaugurado Ricci Hall, um albergue jesuíta, durante todos os 7 anos de meus estudos na Universidade.

Ganhe $8 por mês

Em 1 de janeiro de 1939, aos 24 anos, fui nomeado Oficial Médico Cirúrgico do Departamento Médico de HK no Hospital Kowloon. Mas lembre-se de que havia cordas presas. Enquanto de ascendência e status portugueses como reconhecidos no meu país natal, aqui na colônia britânica, eu ainda era legalmente classificado como chinês. O meu concorrente era o Dr. G.A.V. Griffith, um britânico de 45 ou 50 anos de idade. Nós dois realizamos todas as cirurgias para este Hospital Civil do Governo. Nossa carga de trabalho foi medida em termos de serviços gratuitos, para 100.000 pessoas, 24 horas por dia.

Meu salário agora era de 375 dólares de Hong Kong por mês, ou 62,50 dólares americanos. A cada ano, o salário aumentava em 25 dólares de Hong Kong por mês. Nós, oficiais médicos chineses, tínhamos 2 semanas de licença por ano. Os oficiais médicos ingleses tinham 9 meses de licença a cada 3 anos, com passagem 2 e vindos do Reino Unido para toda a família. Esse status era permanente em nosso contrato durante o período pré-guerra, independentemente de nossos anos de serviço no governo de Hong Kong. Era, como diria um médico, uma pílula amarga de engolir.

Japão invade HK, sou voluntário para prisioneiros de campo de guerra

Planos de emergência foram feitos com antecedência. Nesse momento, eu deveria chamar meu oficial cirúrgico sênior, Dr. Issac Newton (em inglês). Ele me designou de volta para o hospital Kowloon, que ficava perto do Aeroporto Kai Tak. O aeroporto foi o principal alvo da força aérea japonesa. As vítimas estavam entrando nos centros de emergência em Kowloon.

De segunda a quinta-feira, trabalhamos como cães em vítimas sem número. Em seguida, os japoneses superam Kowloon. Todo o trabalho acabou. Não havia gás, nem eletricidade, nem equipamento esterilizado para cirurgia. Nós do Hospital Kowloon fomos simplesmente isolados. Não havia mais ambulâncias funcionando. Nenhum caso a chegar.

Na manhã de quinta-feira, 12 de dezembro, um soldado japonês solitário com um rifle subiu a unidade do hospital. Cerca de 150 metros atrás veio um sargento com uma espada e um revólver. Os dois assumiram o hospital sem resistência.

No 11o dia do nosso cativeiro fomos levados para o Hotel Kowloon na ponta da península… Não estávamos totalmente instalados no hotel quando tivemos um visitante. Ele era um oficial médico sênior do Exército Japonês. Seu nome era Major Konishi. Ele tinha um problema. Prisioneiros de guerra feridos britânicos estavam sendo mantidos em um acampamento na Argyle Street. A guerra ainda estava em fúria em HK. As baixas japonesas como a nossa, foram pesadas. Os japoneses foram amarrados para o pessoal médico para suas próprias necessidades. Alguns de nós se voluntariariam para servir nossas próprias vítimas na Argyle Street?

Os três oficiais médicos seniores eram de origem britânica. Eles, é claro, se ofereceram para cuidar dos seus. Fui classificado como um oficial médico júnior por causa do meu status chinês. É o mesmo Dr. Newton disse: “Eddie, você também vem, você tem que me ajudar”.

Eu não precisava “vir também”. Havia uma saída para mim. Uma forma que significa liberdade em Macau. Macau era uma colónia portuguesa a apenas 64 km de distância e Portugal não estava em guerra com o Japão. De facto, o Governador de Macau, na altura, emitia um convite aos médicos de origem portuguesa da Hong Kong, mas com diplomas britânicos para praticar livremente em Macau. Mas meu médico sênior me concedeu igual dignidade na profissão e agora ele precisava de mim. E quem, mais do que vítimas da guerra, precisava mais dos nossos serviços? Foi incutido em nossa família para servir onde havia necessidade. Eu sou voluntário. …

Tente imaginar este acampamento através dos olhos de um médico: algumas dezenas de cabanas de zinco abrigam 20 a 30 pessoas cada. Não há camas. Pacientes e médicos dormiam em pranchas apoiadas acima do nível do solo Meu trabalho era o trabalho sujo de limpar e curar feridas. Havia tantos feridos que levavam longas horas por dia…

Não é fácil descrever as circunstâncias em tais campos de prisioneiros. Antes da guerra, eu tinha sido um excelente atleta em HK. Meu peso ao entrar no acampamento, era uma luta de 155 libras. Ele caiu para 130 quilos na dieta de fome. Os prisioneiros feridos, apesar de seus ferimentos, não receberam tarifa melhor. Além disso, havia sempre o medo mortal, pairando sobre nós como a espada de Dâmocles, de cometer alguma infração. Um e todos conheciam o tratamento destinado aos infratores do exército japonês. A penalidade por qualquer transgressão do suposto código da Ocupação Japonesa, foi a morte por decapitação na rua.

Encalhado entre os prisioneiros

Agora, na Argyle Street, o Dr. Newton fez uso de sua posição como cirurgião para sair da prisão e residir em um hospital civil chamado St. Hospital de Theresa em Prince Edward Road. Dr. Uttley teve um ataque com disenteria e foi tratado em St Theresa e, em seguida, enviado para o campo de prisioneiros civis em Stanley em HK.

Isto deixou o Dr. Hargreaves e eu encalhados como bagagem excedente no campo de prisioneiros de guerra na Argyle Street. Em seguida, eles nos transferiram para o acampamento Sham Shui Po, um campo de prisioneiros para outras fileiras ou ORs, de todas as forças – britânicas, canadenses, indianas, eurasianas, portuguesas – que haviam lutado por HK.

Havia quase 200 macaenses (português) nestes campos de prisioneiros. Entre eles, além de mim, estavam meus três irmãos mais novos, Luigi, Jerry e Zinho, que todos se ofereceram para a defesa da HK. Zinho foi enviado ao Japão para trabalhar em suas minas de carvão e foi mantido até ser libertado por soldados americanos depois que o Japão se rendeu.

– Dr. Dr. (em inglês). Hargreaves e eu definhamos em Sham Shui Po por meses, apesar de nossos apelos ao comandante japonês que éramos pessoal médico civil. Estávamos em campos de prisioneiros de guerra em primeiro lugar porque tínhamos nos voluntariado quando o major Konishi, o oficial médico japonês, pediu nossa ajuda. Com a guerra terminada e o Corpo Médico do Exército Real mais uma vez disponível, por que ficamos presos como excesso de bagagem por 7 meses sem trabalho frutífero em um campo de prisioneiros militar?

Havia quase 200 macaenses (português) nestes campos de prisioneiros. Entre eles, além de mim, estavam meus três irmãos mais novos, Luigi, Jerry e Zinho, que todos se ofereceram para a defesa da HK. Zinho foi enviado ao Japão para trabalhar em suas minas de carvão e foi mantido até ser libertado por soldados americanos depois que o Japão se rendeu.

– Dr. Dr. (em inglês). Hargreaves e eu definhamos em Sham Shui Po por meses, apesar de nossos apelos ao comandante japonês que éramos pessoal médico civil. Estávamos em campos de prisioneiros de guerra em primeiro lugar porque tínhamos nos voluntariado quando o major Konishi, o oficial médico japonês, pediu nossa ajuda. Com a guerra terminada e o Corpo Médico do Exército Real mais uma vez disponível, por que ficamos presos como excesso de bagagem por 7 meses sem trabalho frutífero em um campo de prisioneiros militar?

Em junho de 1942, o Dr. Gosano foi autorizado a deixar o campo de prisioneiros de guerra e retornar à sua família. Pouco tempo depois, foi convidado pelo colega português HLP Ozorio para trabalhar no Consulado Britânico em Macau.

Em junho de 1942, havia 3 médicos de origem portuguesa de HK praticando em Macau. Havia os Drs. Ozorio, G.A.V. O Ribeiro e o J.W. O Barnes. Ao chegar, a chegar a Macau, recebi imediatamente os mesmos privilégios que eles.

Tínhamos nossos próprios consultórios médicos e cobramos o Consulado Britânico pelos serviços prestados. No entanto, o número de refugiados de Hong Kong tornou-se tão grande que estava se tornando uma impossibilidade financeira para o Consulado Britânico acompanhar. Então, nós, 4 médicos, concordamos em receber salários de funcionários. Nossa equipe estava de plantão 24 horas por dia com pelo menos um médico de plantão durante a noite e o dia na clínica do paciente. Visitas domiciliares foram feitas quando necessário. Não fomos autorizados a ver ou tratar pacientes nos hospitais do Governo de Macau e não tivemos privilégios para a cirurgia.

Logo depois de chegar, tive o privilégio de me tornar o médico assistente do cônsul britânico, o Sr. J.P. Reeves (em inglês). Sua filha era Leticia, chamada Tecia. Tecia tinha asma crônica e recorrente. Isso implicava visitas quase diárias à noite, pois seus ataques de asma aguda geralmente vinham ao pôr do sol. Eu me tornei um amigo da família e estava constantemente em sua casa à noite para as refeições e também um jogo de Mah Jong com sua esposa Rhonda e sua secretária de escritório, uma menina portuguesa chamada Micas Gonsalves e o próprio Côrtico.

Enfrentando o Serviço Secreto

Também me tornei médica de uma inglesa chamada Joy Wilson. Seu marido, Geoffrey, era um comissário de polícia da Polícia de Hong Kong. E havia outra senhora inglesa, a Sra. E.J.R. Mitchell, em Macau.

Na Primavera de 1943, as duas mulheres, juntamente com a gestora europeia da empresa eléctrica de Macau, decidiram deixar Macau e tentar passar pelas linhas japonesas até à sede das forças aliadas em Kun Ming, na China.

Depois veio um acontecimento espantoso. Eu não teria ficado surpreso se o marido, o Comissário de Polícia, fosse chefe do serviço secreto britânico. Mas então a Sra. Joy Wilson confidenciou-me que ela era a cabeça do BAAG, o Grupo de Ajuda do Exército Britânico. “Você é a única pessoa em quem sinto que posso confiar, Dr. Gosano”, disse ela.

Por mais incrível que parecesse, pediu-me para tomar a sua posição de cabeça do BAAG subterrâneo em Macau.

Não havia um estado mais suicida para ser pego enquanto ainda vivo, não importa qual seja a sua nacionalidade ou onde você foi pego. Os japoneses também tinham seu balcão no subsolo. E sempre houve essa questão difícil de neutralidade portuguesa – que incidente poderia provocar hostilidades e Portugal se envolveria na Guerra?

Por um lado, o BAAG estava amarrado com alguns piratas do rio, três irmãos chamados Wang. Deviam-se para transportar pessoas através das linhas japonesas em torno de Macau para a sede aliada em Kun Ming (Kunming), China.

Joy Wilson deixou três associados chineses no BAAG de Macau. Eles eram Y.C. Liang (conhecido como P.L.), Fung Bay e N.K. Mar. Liang era um comerciante de arroz com uma pequena loja no centro de Macau perto da Igreja de São Domingos. Ele se tornou um financista rico e proeminente depois da guerra. Fung Bay tornou-se seu braço direito, e ainda trabalha para a família Liang em HK.

O comandante do BAAG era o tenente-coronel L.T. – Anda de comer. Ride foi professor de Fisiologia na Universidade de HK. Quando a guerra chegou, ele estava na Força de Defesa Real de Hong Kong. Ele foi internado com todos os voluntários do RHKDF no campo de prisioneiros de guerra de Shum Shui Po. Mas quase imediatamente seu secretário chinês pessoal chegou ao pareado em um lixo e o Professor Ride conseguiu escapar por cima da parede. Os dois fizeram o seu caminho para Kunming, na China. There Ride organizou o BAAG com ele mesmo como Comandante.

Eu o conhecia desde os meus dias de críquete na Universidade de HK. Durante 1935 e 36 eu era capitão da equipe estudantil que jogou a faculdade no que foi chamado de Jogo Anual Phoenix. Agora, em nossa nova associação no BAAG, cada um de nós tinha um nome de código. Tenho a certeza que o tenente. – Coronel. O Ride estava a chamar a atenção daqueles dias de críquete quando me deu o nome de código Phoenix.

Ser um médico praticante fez a minha amizade com o cônsul britânico bastante plausível e a minha clínica médica foi a cobertura perfeita para os agentes britânicos que visitam Macau. A função do BAAG em Macau era correlacionar qualquer informação que pudesse ser importante para o exército britânico. Também fomos úteis para as necessidades de pessoal dos Aliados. Houve um tempo em que três aviadores americanos foram abatidos em torno de Canton, na China. Um era um piloto de caça e os outros dois eram piloto e artilheiro em um porta-aviões de torpedos. Eles foram apanhados por pescadores e levados para Macau para o Cônsul Britânico. Os piratas fluviais e do nosso grupo levaram os três para a China.

Em qualquer ponto ao longo desta cadeia de intrigas, se os japoneses tivessem detectado o resgate, as cabeças teriam caído e possivelmente uma briga entre Portugal e o Japão poderia ter ocorrido. Eu vivia em uma fase constante de apreensão, me perguntando por que eu tinha concordado em aliviar a Sra. Joy Wilson. Ser um agente disfarçado trabalhando contra um inimigo mortal e astuto não era um perigo imaginário. Foi real. Eu carreguei uma pequena pistola para os anos do meu trabalho com o BAAG. Apesar do medo permanente da execução, eu permaneci com os outros no serviço secreto até que o Japão se rendeu e a ocupação cessou.

Fuga de Leo d’Almada

O Honorável Leo d’Almada foi o principal representante da comunidade portuguesa em HK. O Sr. d’Almada foi um QC (Membro do Conselho das Rainhas), bem como membro do Conselho Executivo do Governo HK. Ele foi alojado num pavilhão na quadra de ténis do Governador de Macau.

O cônsul britânico recebeu uma mensagem do governo britânico. O Cônsul deveria dizer a d’Almada que o governo queria que ele, na Inglaterra, participasse da organização de uma força-tarefa preparada para retomar e reabilitar HK quando o Japão acabaria sendo derrotado. O Sr. d’Almada conhecia bem os perigos de tentar fugir para a Inglaterra através da rede japonesa. Ele recusou a convocação.

O governo britânico pediu-me através do BAAG para ver o Sr. d’Almada. Como estávamos familiarizados socialmente, eu poderia me dirigir a ele pessoalmente. “Leo” eu disse, “como chefe do BAAG em Macau, eu sei desta mensagem da Inglaterra. Como português sênior em HK, é muito importante para nós, portugueses, bem como para os súditos britânicos, para você ir para a Inglaterra. Nossa organização irá levá-lo com segurança para Kunming e depois para Londres.

Sua obrigação deve ter pesado em sua consciência. Ele não afrontou a minha ousadia. O que o preocupava era a ideia de deixar sua esposa em tal abandono precário caso fosse pego. “Poderia Tilly também?” Ele perguntou “não tenho certeza”, eu disse. “Vou perguntar a Y.C. Liang (em inglês). Ele estará diretamente envolvido”.

Leo e Tilly d’Almada foram entregues com segurança através dos perigos por nossos agentes subterrâneos. O Sr. d’Almada voltaria a Hong Kong um dia, preparado para a aquisição provisória do Governo.

Epílogo

Imediatamente após a guerra (em 26 de novembro de 1945), o Dr. Gosano casou-se com Hazel Lang, uma menina eurasiana que tinha sido sua vizinha em Kowloon, na igreja de Santa Teresa. Eles tiveram três filhas Stephanie, Susanne e Edwina.

Dr. Gosano retornou ao Hospital Kowloon após a guerra como um “oficial médico chinês”. Ele foi então designado para o Hospital Queen Mary para cirurgia geral e de ouvido, nariz e garganta. Apesar de seus esforços heróicos durante a guerra e por seu trabalho perigoso para o BAAG, ele foi submetido à contínua discriminação colonial a serviço do governo de Hong Kong.

Foi apenas com a intervenção de seu companheiro seguinte BAAG, Major Bevan Field da HK Investment Company (HK Land) e HK Volunteers, ele finalmente conseguiu criar um consultório particular na Edinburgh House 14 anos após sua formatura.

Em 1950 foi convidado para servir como membro do Conselho Urbano, representando os interesses portugueses em HK, substituindo o Dr. A.M. Rodrigues (em inglês). Ele serviu nesta capacidade para os próximos 10 anos, particularmente em comitês selecionados sobre saúde pública. Em suas próprias palavras “Este serviço foi sem qualquer tipo de remuneração, exceto pela apreciação das pessoas que servimos”.

1953: Lelaine Mok, Gordon Randall, Tracy Brown, Hazel and Dr Eddie Gosano

O Dr. Gosano também continuou seu serviço como oficial médico com o Regimento HK da Força de Defesa voluntário em 1949 com o posto de capitão. Ele subiu para oficial médico sênior do regimento HK com o posto de Major em 1955.

Ele migrou para os Estados Unidos em 1960, garantindo uma posição como estagiário no Hospital St Joseph, em São Francisco. Na época, as qualificações médicas de Hong Kong não eram reconhecidas lá e ele era obrigado a servir 3 anos como estagiário maduro de 46 anos para completar seu diploma de MD nos EUA.

Morreu em São Francisco aos 96 anos.