Guia – fortress, chapel and lighthouse

by Stuart Braga

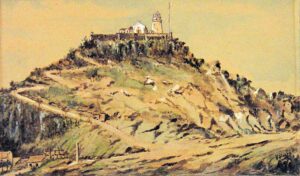

Macau in 1835. This picture appeared in Anders Ljungstedt’s book. The three hills are Guia on the right, Monte Fort in the centre and Penha on the left.

More than 300 years ago as mariners approached Macau the first glimpse they had of this tiny European outpost in East Asia was a little chapel perched improbably at the top of a steep hill. After months at sea, perhaps calling at various ports in East Africa and South Asia, sailors were keen to see something familiar. The sight of this European building must have been a considerable thrill. The chapel was dedicated to Our Lady of the Snows in reference to the ancient church built on top of the Esquiline Hill, one of the original Seven Hills of Rome, but is more commonly known as capela de Nossa Senhora da Guia, the chapel of Our Lady of Guidance.

Guidance has always been the role of Guia. The Swedish merchant Anders Ljungstedt, who wrote the first history of Macau in English, published in 1836, commented on the importance of Guia in the guidance of ships. He wrote: “the fort of Guia serves during daylight as a guidance for ships steering for Macao and Canton. When a ship is descried [i.e. sighted] the Governor is advised by signals of her approach, and when her flag can be discerned by writing, the commanding officer sends down to him. On the arrival of a Portuguese vessel a bell is rung.”(1) This bell, originally cast in 1707, still hangs in a small belfry about two metres high. It bears a dedicatory inscription set into the bell when it was recast in 1824, indicating that it was then consecrated and baptised with the names of Mary by the Most Excellent Bishop and Governor, Dom Friar Francisco de Nossa Senhora da Luz Chassim on 30 June that year. (2)

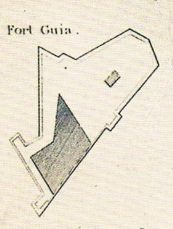

The fortress built around the steep sides of Guia Hill predates the chapel. Guia was already partially fortified by 1622, when the Dutch attempted to seize Macau on the feast day of St. John the Baptist, 24 June. Guia played a significant role in repelling the Dutch, who had landed a little to the North East and began to advance on the city. A shot from Monte fortress set off an explosion in the wagon in which the Dutch had their ammunition, whereupon they retreated in disorder, having sustained many casualties, including most of their officers. Attempting to regroup, they decided to climb Guia Hill to get a better view of their enemy, but their ascent was resisted by a small party of thirty men, whose ferocity and effective use of the high terrain forced the Dutch to abandon this plan. Retreat soon became a rout and the Dutch, who had greatly outnumbered the Portuguese defenders, returned to their base in Batavia.

Thereafter the fortifications were strengthened in earnest. The towering walls and the fort above them were completed in 1638 in the expectation of a renewed Dutch attack. This never happened, but Guia remained a military area until 1976. The completion of the fort was marked by a stone bearing the Portuguese royal arms. This seems to have been an act of defiance by the Macau Council, soon to be known as the Leal Senado, against Spanish authority, since Portugal was under Spanish rule from 1580 until 1640. Beneath the royal arms of Portugal is an inscription, reading, in translation:

THE CITY ORDERED THIS FORT TO BE BUILT AT ITS OWN EXPENSE BY CAPTAIN OF THE ARTILLERY ANTÓNIO RIBEIRO RAIA. IT WAS STARTED IN SEPTEMBER 1637 AND WAS FINISHED IN MARCH 1638, THE GENERAL THEN BEING DA CAMARA DE NORONHA.

It seems that the chapel was built at the same time, perhaps replacing an earlier ‘hermitage’, for the defenders of Macau relied on spiritual as well as physical resources. Plainly, the chapel was built as part of the defensive structure, for the walls and roof are very solidly constructed. Beneath its red-tiled pitched roof, the tiny chapel has a barrel vault ceiling for strength. In the centre, a thick Romanesque arch supports the roof; this building was meant to withstand cannon fire. Therefore it has few windows. A miniature quatrefoil window at the western end lets in light above the small doorway. Like so many baroque churches, the chapel is decorated with frescoes on the walls and ceilings, but by the time the chapel was completely restored between 1998 and 2001, many had deteriorated beyond recovery. Led by a team of experts, the restoration of the surviving frescoes took three years. The frescoes mostly show vines and flowers. There are several angels, but only one saint. Perhaps in a pointed reference to the repulse of the Dutch attack on his feast day, this is St John the Baptist. Unlike most representations, St John is not shown baptising Jesus. He is a boy, cradling a tiny lamb in his left hand. It is a powerful image of protection; perhaps the little lamb was Macau itself.(3)

Protection is what Guia was good at. As late as World War II, several concrete bunkers fitted with anti-aircraft guns were built along the ridge running north from the ancient fortress. It seems that the guns were never used, though in a series of American raids in January 1945 the nearby hangar used by PanAm as the shore base for its pre-war flying boat service was attacked. This had been used to store aviation fuel, potentially useful to the Japanese. Naturally, the fuel was destroyed in this raid.

A quite different idea of protection was the construction in 1864 of the first lighthouse on the China coast. Using machinery designed by a Macanese citizen, Carlos Vicente da Rocha, it was first lit on 24 September 1865, originally with a kerosene lamp.(4)

It seems that the chapel was built at the same time, perhaps replacing an earlier ‘hermitage’, for the defenders of Macau relied on spiritual as well as physical resources. Plainly, the chapel was built as part of the defensive structure, for the walls and roof are very solidly constructed. Beneath its red-tiled pitched roof, the tiny chapel has a barrel vault ceiling for strength. In the centre, a thick Romanesque arch supports the roof; this building was meant to withstand cannon fire. Therefore it has few windows. A miniature quatrefoil window at the western end lets in light above the small doorway. Like so many baroque churches, the chapel is decorated with frescoes on the walls and ceilings, but by the time the chapel was completely restored between 1998 and 2001, many had deteriorated beyond recovery. Led by a team of experts, the restoration of the surviving frescoes took three years. The frescoes mostly show vines and flowers. There are several angels, but only one saint. Perhaps in a pointed reference to the repulse of the Dutch attack on his feast day, this is St John the Baptist. Unlike most representations, St John is not shown baptising Jesus. He is a boy, cradling a tiny lamb in his left hand. It is a powerful image of protection; perhaps the little lamb was Macau itself.(3)

This did not mean that the Guia lighthouse was useless. It doubled as a weather station and being on the highest point in Macau, it was in the ideal position for signals warning of approaching typhoons. There were ten signals of different shapes, made of wickerwork and painted black. When severe conditions threatened, these signals were hoisted according to the meteorological outlook. Anything above No. 8 was serious, and No. 10 warned of an approaching catastrophe. This is actually what happened in 1874, when the Great Typhoon devastated Macau, killing thousands of people. Among the many buildings that had to be rebuilt was the lighthouse itself, though the sturdy chapel survived the tempest.

The vast casinos of modern Macau dwarf all its ancient buildings, crowding around them and towering over many. Guia, often neglected and less visited than the other iconic and more accessible World Heritage sites, deserves more attention than it receives.

Guia – fortaleza, capela e farol

Stuart Braga

Macau em 1835. Esta foto apareceu no livro de Anders Ljungstedt. As três colinas são Guia à direita, Monte Forte no centro e Penha à esquerda.

Mais de 300 anos atrás, quando os marinheiros se aproximaram de Macau, o primeiro vislumbre deste pequeno posto avançado europeu no leste da Ásia foi uma pequena capela empoleirada improvável no topo de uma colina íngreme. Depois de meses no mar, talvez chamando em vários portos da África Oriental e do Sul da Ásia, os marinheiros estavam ansiosos para ver algo familiar. A visão deste edifício europeu deve ter sido uma emoção considerável. A capela foi dedicada a Nossa Senhora das Neves em referência à antiga igreja construída no topo do Monte Esquiline, uma das Sete Colinas originais de Roma, mas é mais comumente conhecida como a capela de Nossa Senhora da Guia, a capela de Nossa Senhora da Guia.

A orientação sempre foi o papel da Guia. O comerciante sueco Anders Ljungstedt, que escreveu a primeira história de Macau em Inglês, publicado em 1836, comentou sobre a importância do Guia na orientação dos navios. “O forte da Guia serve durante o dia como orientação para os navios que se dirigem para Macau e Cantão. Quando um navio é descrito, o Governador é aconselhado por sinais de sua aproximação, e quando sua bandeira pode ser discernida por escrito, o comandante envia para ele. Na chegada de um navio português é tocado um sino.”( 1) Este sino, originalmente lançado em 1707, ainda está pendurado em um pequeno campanário de cerca de dois metros de altura. Tem uma inscrição dedicatória colocada no sino quando foi reformulada em 1824, indicando que foi então consagrada e batizada com os nomes de Maria pelo Mais Excelente Bispo e Governador, Dom Frei Francisco de Nossa Senhora da Luz Chassim, em 30 de junho daquele ano. (2)

A fortaleza construída em torno dos lados íngremes da Guia Hill é anterior à capela. A Guia já estava parcialmente fortificada em 1622, quando os holandeses tentaram tomar Macau no dia da festa de São Paulo. João Batista, 24 de junho. A Guia desempenhou um papel significativo em repelir os holandeses, que haviam desembarcado um pouco para o Nordeste e começou a avançar sobre a cidade. Um tiro da fortaleza de Monte desencadeou uma explosão no vagão em que os holandeses tinham sua munição, após o que recuaram em desordem, tendo sofrido muitas baixas, incluindo a maioria de seus oficiais. Tentando se reagrupar, eles decidiram escalar a Montanha Hill para obter uma visão melhor de seu inimigo, mas sua ascensão foi resistida por um pequeno grupo de trinta homens, cuja ferocidade e uso efetivo do terreno alto forçaram os holandeses a abandonar este plano. Retreat logo se tornou uma derrota e os holandeses, que haviam superado em muito o número dos defensores portugueses, retornaram à sua base em Batávia.

Depois disso, as fortificações foram fortalecidas a sério. As imponentes paredes e o forte acima deles foram concluídas em 1638 na expectativa de um novo ataque holandês. Isso nunca aconteceu, mas a Guia permaneceu uma área militar até 1976. A conclusão do forte foi marcada por uma pedra com as armas reais portuguesas. Este parece ter sido um acto de desafio pelo Conselho de Macau, que em breve será conhecido como o Leal Senado, contra a autoridade espanhola, uma vez que Portugal estava sob domínio espanhol de 1580 até 1640. Sob as armas reais de Portugal há uma inscrição, lendo, em tradução:

THE CITY ORDERED THIS FORT TO BE BUILT AT ITS OWN EXPENSE BY CAPTAIN OF THE ARTILLERY ANTÓNIO RIBEIRO RAIA. IT WAS STARTED IN SEPTEMBER 1637 AND WAS FINISHED IN MARCH 1638, THE GENERAL THEN BEING DA CAMARA DE NORONHA.

Parece que a capela foi construída ao mesmo tempo, talvez substituindo uma “emissão” anterior, pois os defensores de Macau dependiam tanto de recursos espirituais quanto físicos. Claramente, a capela foi construída como parte da estrutura defensiva, pois as paredes e o telhado são construídos de forma muito sólida. Sob seu telhado inclinado de azulejos vermelhos, a pequena capela tem um teto de abóbada de barril para força. No centro, um grosso arco românico suporta o telhado; este edifício foi concebido para suportar o fogo de canhão. Por isso, tem poucas janelas. Uma janela de quatrefoil em miniatura na extremidade ocidental deixa entrar em luz acima da pequena porta. Como tantas igrejas barrocas, a capela é decorada com afrescos nas paredes e tetos, mas quando a capela foi completamente restaurada entre 1998 e 2001, muitos se deterioraram além da recuperação. Liderado por uma equipe de especialistas, a restauração dos afrescos sobreviventes levou três anos. Os afrescos mostram principalmente videiras e flores. Existem vários anjos, mas apenas um santo. Talvez em uma referência à repulsa do ataque holandês em sua festa, este é São João Batista. Ao contrário da maioria das representações, São João não é mostrado batizando Jesus. Ele é um menino, embalando um minúsculo cordeiro na mão esquerda. É uma imagem poderosa de proteção; talvez o cordeiro pequeno fosse o próprio Macau.(3)

This did not mean that the Guia lighthouse was useless. It doubled as a weather station and being on the highest point in Macau, it was in the ideal position for signals warning of approaching typhoons. There were ten signals of different shapes, made of wickerwork and painted black. When severe conditions threatened, these signals were hoisted according to the meteorological outlook. Anything above No. 8 was serious, and No. 10 warned of an approaching catastrophe. This is actually what happened in 1874, when the Great Typhoon devastated Macau, killing thousands of people. Among the many buildings that had to be rebuilt was the lighthouse itself, though the sturdy chapel survived the tempest.

The vast casinos of modern Macau dwarf all its ancient buildings, crowding around them and towering over many. Guia, often neglected and less visited than the other iconic and more accessible World Heritage sites, deserves more attention than it receives.