The Border Gate, or Portas do Cerco

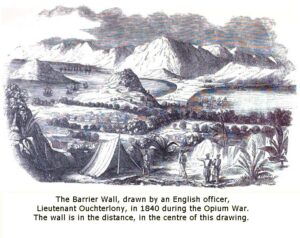

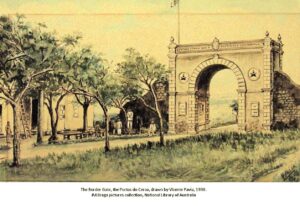

The boundary between Macau and what is commonly called the Mainland is now defined by tall buildings and a well-organised border post, some 3 km from the centre of Macau. In the middle of these modern buildings there is an old-fashioned arch erected in 1870 as a triumphal statement of Portugal’s victory over China 21 years earlier. However for most of the previous three centuries, the boot was on the other foot. In 1573, sixteen years after the Portuguese arrived in Macau, the Chinese authorities on Heung Shan Island, of which Macau is a part, decided that these strange people whom they termed Western Barbarians must be kept under control. In China, as in Europe at that time, this meant building a wall. Therefore a wall was hastily constructed across the narrowest point of the small peninsula on which the Portuguese had settled. Now known as the Border Gate, it was then the Barrier Wall, with only one gate. What did this mean?

Did it mean that the Chinese Empire had given this land to Portugal? On the other hand, was this the first stage of a siege at the end of which the Portuguese might be pushed out or exterminated, which is what the Japanese did in 1640 to the members of a Portuguese embassy seeking to re-establish trade with Japan? Neither of these is true. It seems to have been an ad hoc measure to control both the people in Macau and those who came to trade with them. This trade was essential, because Macau was a barren, rocky outcrop unable to grow its own food, and even supplies of fresh water were precarious.

Each week a market was held on the south side of the gate through which Chinese traders, chiefly vegetable growers, were allowed to enter a small area of land marked out as a market place. After a few hours, the traders were sent back and the gate was closed until the following week. Above the gate was an inscription on the Portuguese side, ‘Western Barbarian Gate’ and there were two signs instructing the Portuguese ‘dread our greatness’ and ‘respect our virtue’. The implied menace is obvious. To ensure that all requirements were observed, the Heung Shan Mandarin erected a compound on high ground some distance away from the wall. It was painted white so that it could not be ignored, and was termed by the Portuguese the Casa Branca, the White House.

Almost the only time Portuguese people were allowed on the northern side of the gate was when a delegation from the Council of Macau, the Leal Senado, came with some special request or to pay an annual rent amounting to $500. They were obliged to make obeisance, the infamous kow tow, to the mandarin. A visiting Spanish Dominican friar, Domingo Navarrete, writing in 1672, saw what happened.

The kow tow was a humiliating grovel and when King João V of Portugal heard about it in 1712, he forbade his subjects to perform it. However, Lisbon was 11,000 km away, and the people in Macau had no option but to do as the mandarin demanded.

If something happened to displease the magistrate, the gate was shut and the weekly market closed until Macau submitted to his will; the mere threat was usually sufficient, but in 1662, the gate was closed for three months and many people starved to death. There was no other way of bringing food in. Why did the Portuguese not attack the wall and force the Chinese to submit? The answer is that the fortifications of Macau, which seem quite impressive to the modern visitor, were only defensive and there was no capacity to attack.

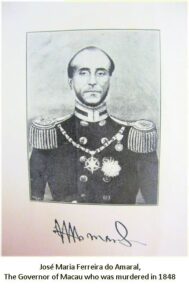

At the top of the arch is inscribed a famous quotation from the great Portuguese poet Luís de Camões: ‘A pátria honrai, que a pátria vos contempla‘ (‘Honour your country, for your country looks after you’). On the walls of the arch were tablets, one bearing the date of Governor Amaral’s death and the other, the heroic charge of Mesquita, who avenged his death.

Two more plaques bear the dates when the arch was commenced and completed: 22 August 1870, the 21st anniversary of Amaral’s murder, and the date of the arch’s completion, 31 October 1871. A further adornment is a series of azulejos, lovely Portuguese blue tiles celebrating the achievements of Portuguese exploration over the previous 400 years.

A century after Amaral’s murder, the frontier was closed once again. For many years after the Chinese Revolution in 1949, the Portas do Cerco was a no-go area. Only local people bringing farm produce to sell in Macau were permitted to cross. Sir Lindsay Ride, the Vice-Chancellor of Hong Kong University, who took a keen interest in the history of Macau, was not allowed to go there to look at the inscriptions. In 1952 there was a major border incident when Portuguese African troops exchanged fire with Chinese border guards. The exchange lasted for more than an hour, leaving one dead and several dozens injured on the Macau side and an unknown number of casualties on the Chinese side. After the death of Chairman Mao, tensions relaxed and the border gradually reopened.

Now, in the 21st century, all the statements asserting or denying sovereignty and conquest can be set aside. Macau is no longer terrorised by Chinese mandarins, while the Chinese no longer feel humiliated by the boastful arch built to proclaim their defeat at the hands of the Portuguese. Where once local farmers selling vegetables, pigs and poultry were allowed through the barrier gate once a week, up to 50,000 tourists now come from the mainland each day to gamble in Macau’s casinos. However, the old arch remains as a reminder of an era when times were more difficult and attitudes far less friendly.

O Portão da Fronteira, ou Portas do Cerco

A fronteira entre Macau e o que é vulgarmente chamado de Continente é agora definida por edifícios altos e um posto fronteiriço bem organizado, a cerca de 3 km do centro de Macau. No meio desses edifícios modernos há um arco antiquado erguido em 1870 como uma declaração triunfal da vitória de Portugal sobre a China 21 anos antes. No entanto, durante a maior parte dos três séculos anteriores, a bota estava no outro pé. Em 1573, dezesseis anos depois de os portugueses chegarem a Macau, as autoridades chinesas na ilha Heung Shan, da qual Macau faz parte, decidiram que estas pessoas estranhas a quem chamaram de Bárbaros Ocidentais deviam ser mantidas sob controlo. Na China, como na Europa naquela época, isso significava construir um muro. Portanto, um muro foi construído às pressas através do ponto mais estreito da pequena península em que os portugueses tinham se estabelecido. Agora conhecido como o Portão da Fronteira, era então a Muralha da Barreira, com apenas um portão. O que significa isto?

Isso significava que o Império Chinês tinha dado esta terra a Portugal? Por outro lado, foi esta a primeira etapa de um cerco no final da qual os portugueses poderiam ser expulsos ou exterminados, que é o que os japoneses fizeram em 1640 aos membros de uma embaixada portuguesa que procurava restabelecer o comércio com o Japão? Nenhum deles é verdade. Parece ter sido uma medida ad hoc para controlar tanto as pessoas em Macau como as que vieram para o comércio com eles. Esse comércio era essencial, porque Macau era um afloramento estéril e rochoso incapaz de cultivar sua própria comida, e até mesmo o suprimento de água doce era precário.

A cada semana, um mercado era realizado no lado sul do portão através do qual os comerciantes chineses, principalmente os produtores de vegetais, podiam entrar em uma pequena área de terra marcada como um mercado. Depois de algumas horas, os comerciantes foram enviados de volta e o portão foi fechado até a semana seguinte. Acima do portão havia uma inscrição no lado português, “Portão Bárbaro Ocidental” e havia dois cartazes instruindo os portugueses “medo a nossa grandeza” e “respeitam a nossa virtude”. A ameaça implícita é óbvia. Para garantir que todos os requisitos fossem observados, o mandarim Heung Shan ergueu um composto em terreno alto a alguma distância da parede. Foi pintado de branco para que não pudesse ser ignorado, e foi denominado pelos portugueses a Casa Branca, a Casa Branca.

Quase a única vez que os portugueses foram autorizados no lado norte do portão foi quando uma delegação do Conselho de Macau, o Leal Senado, veio com algum pedido especial ou pagar um aluguel anual no valor de 500 dólares. Eles foram obrigados a fazer reverência, o infame reboque, ao mandarim. Um frade dominicano espanhol visitante, Domingo Navarrete, escrevendo em 1672, viu o que aconteceu.

Eles vão em um corpo com varas nas mãos para o Mandarino que reside uma Liga de então e eles pedem-lhe em seus joelhos. A Mandarina em sua Resposta escreve assim: “Esta povo bárbara e brutal deseja tal e tal coisa: que seja concedida”. Ou ‘recusou-os’… se o rei deles soubesse dessas coisas, é quase incrível que ele as permitisse.(1)

O kow tow foi um rastejante humilhante e quando o rei D. João V de Portugal ouviu falar sobre isso em 1712, ele proibiu seus súditos para realizá-lo. No entanto, Lisboa estava a 11.000 km de distância, e as pessoas em Macau não tinham outra opção a não ser fazer como o mandarim exigia.

Se algo acontecesse para desagradar o magistrado, o portão estava fechado e o mercado semanal fechado até Macau se submeter à sua vontade; a mera ameaça era geralmente suficiente, mas em 1662, o portão foi fechado por três meses e muitas pessoas morreram de fome. Não havia outra maneira de trazer comida. Por que os portugueses não atacaram o muro e forçaram os chineses a se submeterem? A resposta é que as fortificações de Macau, que parecem bastante impressionantes para o visitante moderno, eram apenas defensivas e não havia capacidade para atacar.

Do ponto de vista chinês, serviu bem ao seu propósito até a Guerra do ópio, 1839-1842. Os britânicos derrotaram os chineses que não estavam em posição de ditar termos aos portugueses, como fizeram por mais de 250 anos. Alguns anos mais tarde, em 1847, o governador de Macau, João Maria Ferreira do Amaral, rejeitando a suserania chinesa sobre Macau, recusou-se a pagar o aluguel anual. As tensões aumentaram, até que, em 22 de agosto de 1849, Amaral foi atacado, morto e decapitado por um grupo de chineses no que equivalia a Terra de Ninguém entre a muralha da cidade de Macau e o muro da barreira mais ao norte. Houve uma reação rápida, e pela primeira vez na história de Macau, os portugueses atacaram os chineses, que tinham sido grandemente enfraquecidos pela sua derrota na Guerra do ópio alguns anos antes. Três dias após a morte de Amaral, o tenente Vicente Nicolau Mesquita liderou uma carga heróica que capturou o forte chinês ao norte do muro da barreira.2 Esse foi o fim do antigo Portão da Barreira com todas as suas conotações de subjugação. 21 anos depois, as Portas do Cerco foram construídas. Parece muito com um arco triunfal romano e essa era realmente a intenção.

No topo do arco está inscrito uma famosa citação do grande poeta português Luís de Camões: “A pátria honrai, que alha a comunidade da pátria” (“Honre o seu país, pois o seu país cuida de você”). Nas paredes do arco estavam tábuas, uma com a data da morte do governador Amaral e outra, a carga heróica de Mesquita, que vingou sua morte.

Mais duas placas têm as datas em que o arco foi iniciado e completado: 22 de agosto de 1870, o 21o aniversário do assassinato de Amaral, e a data de conclusão do arco, 31 de outubro de 1871. Outro adorno é uma série de azulejos, adoráveis azulejos portugueses que celebram as conquistas da exploração portuguesa ao longo dos 400 anos anteriores.

Um século após o assassinato de Amaral, a fronteira foi fechada novamente. Por muitos anos após a Revolução Chinesa em 1949, o Portas do Cerco era uma área proibida. Apenas as pessoas locais que trazem produtos agrícolas para vender em Macau foram autorizadas a atravessar. Sir Lindsay Ride, vice-chanceler da Universidade de Hong Kong, que se interessou muito pela história de Macau, não foi autorizado a ir lá para ver as inscrições. Em 1952, houve um grande incidente na fronteira quando tropas africanas portuguesas trocaram tiros com guardas de fronteira chineses. A troca durou mais de uma hora, deixando um morto e várias dezenas de feridos no lado de Macau e um número desconhecido de vítimas no lado chinês. Após a morte do Presidente Mao, as tensões relaxaram e a fronteira reabriu gradualmente.

Agora, no século 21, todas as declarações afirmando ou negando soberania e conquista podem ser postas de lado. Macau não é mais aterrorizado por mandarins chineses, enquanto os chineses não se sentem mais humilhados pelo arco arrogante construído para proclamar sua derrota nas mãos dos portugueses. Onde antes os agricultores locais que vendiam legumes, suínos e aves eram autorizados a atravessar o portão da barreira uma vez por semana, até 50.000 turistas agora vêm do continente todos os dias para apostar nos casinos de Macau. No entanto, o arco antigo permanece como um lembrete de uma época em que os tempos eram mais difíceis e as atitudes muito menos amigáveis.