The Happy Valley Race Course Fire of 1918

Roy Eric Xavier

April 2012

This article appears in the website Far East Currents, created by Dr Roy Eric Xavier of University of California Berkeley, who is devoted to research on the Portuguese community in Hong Kong. Dr Xavier has kindly given permission for it to be reproduced here.

Prelude

The late winter of February 1918 in Hong Kong was unusually windy and heavy with anticipation. The war in Europe was in its final months, and the effect on trade, now shifting to the Americans and Japanese, was a cause for concern.

Among superstitious Chinese and Europeans, two small earthquakes on the 13th and 14th of February, and an outbreak of spinal meningitis leading to 968 deaths, were ominous signs for the future. Just a few weeks earlier a monsoon had damaged the dock and beach area around North Point. Since then no rain was recorded on the island, and as a result, the weather remained dry and unseasonably warm.

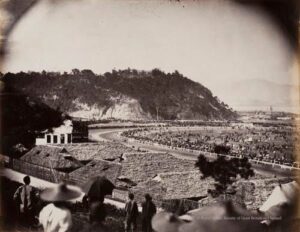

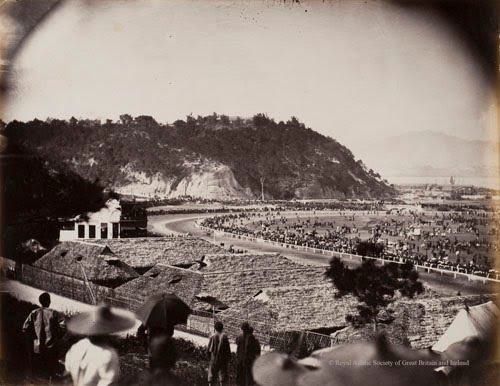

The dry weather, however, suggested to other residents the coming of spring, and with it the opening of the horse racing season at Happy Valley, a traditional event in Hong Kong since 1864.

The “season” had different meanings to many people. To the government, horse racing meant the appearance of “matsheds”, the temporary bamboo and palm leaf structures licensed and built at the race course by enterprising groups of Chinese, Portuguese, Japanese, Indian, and Swedish families.

This required police and fire personnel to perform perfunctory inspections of each structure in anticipation of the 6000 spectators who attended each year, most of whom would inhabit the sheds during the races. The process usually involved informal tours of the stands by young cadets or Chinese “watchmen ” a few days before the races began, and approval was almost never denied.* The scant oversight was also reflected in the usual police presence. Records indicate that 50 regular officers were assigned to the races that year, but none were on duty behind the matsheds, and 8 reserve officers were positioned outside the race course, presumably for crowd control.

Those who were fortunate enough to obtain the permits were considered “men of substance” in their respective communities. Some were landowners or chief clerks. Others ran taverns and boarding houses. A few were stock brokers, or owned printing presses with government contracts.

Each paid the government HK$706 for a single license and HK$180 to build each structure. The total outlay for each matshed was more than one year’s annual wages in the colony, and multiple dwellings were often purchased by large families and licensing groups. Government records indicate that 19 matsheds were built during the 1918 racing season, so the licensing revenue to the government was substantial as well.

The construction of each structure was common for the time. Most matsheds were two or three stories high, measuring about fifty feet tall, and could hold 300 people. Many were erected by Chinese contractors in less than three weeks. The design was based on single story theatrical structures used in religious ceremonies. Depending on the builder, each had a specific blueprint that usually did not vary from year to year.

On the “first” or main level were a large counter and a viewing area, with the only door at the back leading to the street and the tram. Below was a basement level, where a food counter was setup for refreshments, such as tea cakes, pastries, alcoholic drinks and hot tea. The food was kept warm on several charcoal “chatties” kept by the vendor.

Derby Day 1918

On Tuesday February 26th, took the Star Ferry from Kowloon to meet his good friend for lunch at Wiseman’s restaurant in downtown Hong Kong. Aureliano was a well-to-do member of a prominent merchant family and the father of thirteen children, with another due in April. Carlos was a distinguished Macanese diplomat and the father of eleven children.

Carlos and Aureliano shared a love of horse racing and gambling with many in the Portuguese community. It was not unusual for entire families to attend the races together and place bets on their favorite thoroughbreds. The children, at least those too young to gamble, often mimicked their elders.

Carlos’ youngest son, , who was twelve at the time and attended the races that day, described how boys would write down the names of horses on small pieces of paper, then scribbled their own names, as would-be “bookies”, on the back.

On this particular day, Carlos was struck by Aureliano’s persistence about joining him for the “Derby”, and noted his own regrets because of a previous engagement at the Club de Recreio later that afternoon. So Carlos accompanied Aureliano to the tram stop, bidding him good luck on his way to Happy Valley, then took the ferry back to Kowloon.*

On that same morning, John Olson II, the son of a Swedish landowner and tavern manager, was at the race course to inspect “stands” No. 4, 5, and 6, the matsheds he owned with his business partners, J.J. Blake and Charles Warren, who was also Olson’s brother-in-law. Olson had hired the Chinese firm, Taz Hop, to construct the three structures in early February, but the crew of seventy workmen had only completed the work on the 24th. *

Four years earlier, Olson had complained in vain to the Clerk of the Course that adjoining matsheds, which stood three stories high, were too weak and had given way, compromising his own structures. In 1918 Olson instructed his workers to build only two story matsheds, but neglected to specify that supporting struts be driven into the ground. Instead the Taz Hop crew, as was tradition, lashed Olson’s stand to the adjoining structures that were being built at the same time.

Olson did, however, order his contractors to put “double uprights” to reinforce the betting and refreshments counter on the bottom floor, expecting, as he stated later, “more of a crush at the counter” that year. In No. 6, Olson also allowed the use of charcoal “chatties” for cooking by a Chinese vendor, M.Y. San, but instructed San to have three large barrels of water on the bottom floor, and eight full fire buckets on the upper floor.

After the morning races ended, , one of the owners of his family’s stand at No. 7, joined several relatives and friends for lunch. They included his stepbrothers and , and nephews and , who were eighteen and twenty years old, and niece , who was sixteen. The younger relatives were the siblings of , the owner of the Hong Kong Printing Press. They were probably joined by at least seven other members of the Portuguese community from Hong Kong and Kowloon.

Francisco had instructed his contractor to build a three story matshed for the 1918 season. The ground floor was used for refreshments, which were sold by Chinese employees. The main floor was for pari-mutuel and cash sweeps betting. The top floor, built to only half the size of the lower floor, was reserved for ladies in attendance. Cooking was not allowed that day, but a charcoal chatty was used on the bottom floor to boil water for tea. Francisco also stated there was one entrance on the first floor, but none on the top or bottom floors, adding that the doorway was about six feet wide.

The Collapse and the Fire

As the betting period ended and the horses approached the line, the last thing anyone expected was the chaos and terror that was about to unfold. A reporter for the Hong Kong Daily Press gave this eyewitness account:

Daria’s brother Paulo and others tried to free her, but Paulo was badly burned on his arms in the attempt. Years later, Paulo tearfully related how Daria told him it was no use and to flee for his life. Paulo stayed until the last possible moment, and was almost caught by the flames until a police sergeant pulled him to safety.* A Portuguese police cadet, identified only as “R. Lopes”, is credited with the rescue of several other members of the Xavier family.

Once Bernardino and his friends were on the race course, he noticed smoke rising from the collapsed stands, followed immediately by fires from every side. In less than a minute he wrote that “thousands” who had been trapped under fallen bamboo and palm leaves had no time to escape

He stated that those in the infield were …

The Aftermath

The dead included: , José Libânio Manuel Spencer do Rosário, Gustavo Maria do Rosário, , , Ludovino Leopoldo Xavier, Daria Maria Xavier, Aureliano Guterres Jorge, and . The injured included: Mr and Mrs J. Remedios. There also are unconfirmed reports that members of the d’Aquino family were among the dead. (Correspondence to the author from Fredric “Jim” Silva, April 8, 2012.)

… the service was more than a conventional expression of sympathy. It was indeed an outward manifestation of genuine sorrow, not only for the relatives and friends … but also for the hundreds of human beings who have been victims of an appalling catastrophe.

Recriminations within the Hong Kong government soon followed. Hong Kong’s Coroner noted that:

“… this calamity … could most probably have been prevented by the exercise of foresight … expected before the event…”*

A member of the Legislative Council further pointed to the:

“… neglects and omissions of duty on the part of the Public Works Department (the licensing agency for the stands) and the Police Department (which supervised Hong Kong’s Fire Brigade).”*

Then, to his credit, the Governor permanently banned the use of temporary stands from the race course. The construction of new grandstands was begun soon after.

The ruling and the renovations came too late for the victims of the Happy Valley fire of 1918. The memories of that day have faded along with a lonely memorial erected in 1922 behind the old course.

Horse racing continues at Happy Valley, where the excitement of the racing season attracts thousands each year. But with the passage of time, perhaps the ghosts of the race course tragedy, representing the many ethnic groups that were present in the stands that day, may now rest a little easier knowing that their story has finally been told.

Incêndio no Hipódromo de Happy Valley em 1918

Roy Eric Xavier

Abril 2012

Este artigo foi publicado no site Far East Currents, criado pelo Dr. Roy Eric Xavier, da Universidade da Califórnia em Berkeley, que se dedica à investigação sobre a comunidade portuguesa em Hong Kong. O Dr. Xavier autorizou gentilmente a sua reprodução aqui.

Prelude

O final do inverno de fevereiro de 1918 em Hong Kong foi excecionalmente ventoso e carregado de expectativa. A guerra na Europa estava nos seus últimos meses, e o efeito sobre o comércio, transferindo-se agora para os americanos e japoneses, era motivo de preocupação. *

Entre chineses e europeus supersticiosos, dois pequenos sismos nos dias 13 e 14 de Fevereiro e um surto de meningite espinal que resultou em 968 mortes eram sinais ameaçadores para o futuro. Poucas semanas antes, uma monção tinha danificado o cais e a zona da praia em redor de North Point. Desde então, não foi registada qualquer chuva na ilha e, como resultado, o tempo manteve-se seco e excecionalmente quente. *

O tempo seco, no entanto, sugeriu a outros residentes a chegada da primavera e, com ela, a abertura da temporada de corridas de cavalos no Vale Feliz, um evento tradicional em Hong Kong desde 1864.

A “época” tinha significados diferentes para muitas pessoas. Para o governo, as corridas de cavalos significavam o aparecimento dos “estábulos”, as estruturas temporárias de bambu e folhas de palmeira licenciadas e construídas no hipódromo por grupos empreendedores de famílias chinesas, portuguesas, japonesas, indianas e suecas. *

Isto exigia que a polícia e os bombeiros realizassem inspeções superficiais a cada estrutura, em antecipação dos 6.000 espectadores que compareciam a cada ano, a maioria dos quais habitaria os barracões durante as corridas. O processo envolvia geralmente visitas informais às bancadas por jovens cadetes ou “vigias” chineses alguns dias antes do início das corridas, e a aprovação quase nunca era negada. A escassa fiscalização refletia-se também na habitual presença policial. Os registos indicam que 50 oficiais regulares foram destacados para as corridas nesse ano, mas nenhum estava de serviço atrás dos abrigos de combate, e 8 oficiais da reserva foram posicionados fora da pista de corrida, presumivelmente para controlo de multidões. *

Aqueles que tiveram a sorte de obter as autorizações eram considerados “homens de posses” nas suas respectivas comunidades. Alguns eram proprietários de terras ou escrivães-mor. Outros geriam tabernas e pensões. Alguns eram corretores da bolsa de valores ou proprietários de gráficas com contratos governamentais.

Cada um pagou ao governo 706 HK$ por uma única licença e 180 HK$ para construir cada estrutura. * O desembolso total de cada matshed era superior ao salário anual de um ano na colónia, e as habitações múltiplas eram frequentemente compradas por famílias numerosas e grupos de licenciamento. Os registos governamentais indicam que 19 abrigos para passadeiras foram construídos durante a época de corridas de 1918, pelo que a receita de licenciamento para o governo foi substancial * também.

A construção de cada estrutura era comum na época. A maioria dos abrigos de esteira tinha dois ou três andares de altura, medindo cerca de quinze metros de altura, e podia acomodar 300 pessoas. Muitos foram erguidos por empreiteiros chineses em menos de três semanas. O projeto baseava-se em estruturas teatrais de um só piso utilizadas em cerimónias religiosas. Dependendo do construtor, cada um tinha um projeto específico que geralmente não variava de ano para ano. 8

No “primeiro” nível, ou nível principal, havia um grande balcão e uma área de observação, com a única porta nas traseiras a dar para a rua e para o eléctrico. Em baixo, existia um subsolo, onde estava montado um balcão de alimentos para bebidas, como bolos, doces, bebidas alcoólicas e chá quente. A comida era mantida aquecida em várias “chatties” de carvão mantidas pelo vendedor.

O terceiro piso da estrutura era também uma área de observação e um local popular para a maioria dos apostadores, proporcionando uma vista ampla das corridas. Todo o edifício era suportado por tábuas de bambu ou madeira, por vezes cravadas no solo sob o barracão, mas geralmente simplesmente amarradas a uma árvore, a outra estrutura próxima, se disponível, ou a outros barracões de apostas construídos ao lado. *

As licenças, a construção das bancadas e as apostas, bem como as próprias corridas, faziam parte de uma longa tradição. As ricas bolsas de Happy Valley atraíam ricos proprietários de cavalos de toda a Ásia desde a década de 1860. Cada bolsa era paga pelo elevado volume de apostas “pari-mutuel” e “cash sweeps” permitidas pelo governo em cabines de apostas localizadas no piso principal de cada barracão de apostas.

Os homens da classe média que podiam suportar o investimento inicial obtinham lucros substanciais a cada ano, cobrando uma comissão sobre cada aposta. Muitos alugavam também o piso inferior de cada banca a vendedores de comida e bebida. Esta prática continuou durante algumas décadas, contribuindo para o entretenimento do público e para a riqueza das famílias envolvidas nas festividades anuais em Happy Valley. *

Dia do Derby de 1918

Na terça-feira, 26 de fevereiro, Carlos d'Assumpção apanhou o Star Ferry de Kowloon para encontrar o seu bom amigo Aureliano Jorge para almoçar no restaurante Wiseman’s, no centro de Hong Kong. Aureliano era um membro abastado de uma importante família de comerciantes e pai de treze filhos, estando previsto outro para abril. Carlos era um distinto diplomata macaense e pai de onze filhos.

Carlos e Aureliano partilhavam o amor pelas corridas de cavalos e pelo jogo com muitos na comunidade portuguesa. Não era incomum que famílias inteiras comparecessem juntas às corridas e apostassem nos seus puro-sangues favoritos. As crianças, pelo menos aquelas demasiado novas para jogar, imitavam frequentemente os mais velhos.

O filho mais novo de Carlos, Bernardino, que tinha doze anos na altura e assistiu às corridas nesse dia, descreveu como os rapazes escreviam os nomes dos cavalos em pequenos pedaços de papel e depois rabiscavam os seus próprios nomes, como aspirantes a “apostadores”, no verso.

Corríamos por aí a vender estes “bilhetes” a quem quisesse fazer uma pequena aposta de dez ou vinte cêntimos cada, dependendo da importância das corridas. Naturalmente, retínhamos sempre para nós “uma comissão de dez por cento”, ganhando um ou dois dólares dessa forma: o que para nós era uma fortuna na altura!”

Nesse dia em particular, Carlos ficou impressionado com a persistência de Aureliano em acompanhá-lo ao “Derby” e manifestou o seu próprio arrependimento por um compromisso anterior no Club de Recreio, mais tarde nessa tarde. Assim, Carlos acompanhou Aureliano até à paragem do elétrico, desejando-lhe boa sorte na sua viagem para Happy Valley, e depois apanhou o ferry de volta para Kowloon. *

Na mesma manhã, John Olson II, filho de um proprietário de terras e gerente de uma taberna sueco, estava no hipódromo para inspecionar as “bancadas” nºs 4, 5 e 6, os estábulos que possuía com os seus sócios, J.J. Blake e Charles Warren, que também era cunhado de Olson. Olson tinha contratado a empresa chinesa Taz Hop para construir as três estruturas no início de fevereiro, mas a equipa de setenta operários só concluiu a obra no dia 24. *

Quatro anos antes, Olson queixara-se em vão ao Secretário da Pista que os abrigos para esteiras adjacentes, com três andares de altura, eram demasiado frágeis e tinham cedido, comprometendo as suas próprias estruturas. * Em 1918, Olson instruiu os seus trabalhadores para construírem apenas abrigos para tapetes de dois andares, mas esqueceu-se de especificar que as escoras de suporte deveriam ser cravadas no solo. Em vez disso, a equipa da Taz Hop, como era tradição, amarrou a plataforma de Olson às estruturas adjacentes que estavam a ser construídas ao mesmo tempo.

Olson, no entanto, ordenou aos seus empreiteiros que colocassem “pilares duplos” para reforçar o balcão de apostas e refrescos no piso inferior, esperando, como afirmou mais tarde, “mais aglomeração no balcão” nesse ano. No nº 6, Olson permitiu também o uso de “chatties” de carvão para cozinhar por um vendedor chinês, M.Y. San, mas instruiu San para ter três grandes barris de água no piso inferior e oito baldes de fogo cheios no piso superior.

Após o término das corridas da manhã, Francisco de Paula Xavier, um dos proprietários do stand da sua família no nº 7, juntou-se a vários familiares e amigos para um almoço. Incluíam os seus meios-irmãos José Maria Xavier e Ludovino (Bino) Xavier, e sobrinhos Paulo e Vasco Xavier, que tinham dezoito e vinte anos, e a sobrinha Daria Xavier, que tinha dezasseis anos. Os familiares mais novos eram irmãos de Pedro Xavier, o proprietário da Imprensa de Hong Kong. Provavelmente juntaram-se a pelo menos outros sete membros da comunidade portuguesa de Hong Kong e Kowloon.*

Francisco tinha instruído o seu empreiteiro para construir um barracão de três andares para a temporada de 1918. O rés-do-chão era utilizado para bebidas, vendidas pelos funcionários chineses. O piso principal era utilizado para apostas mútuas e em dinheiro. O piso superior, construído com apenas metade do tamanho do piso inferior, estava reservado às senhoras presentes. * Não era permitido cozinhar nesse dia, mas um grelhador a carvão era utilizado no piso inferior para ferver água para o chá. Francisco afirmou ainda que existia uma entrada no primeiro piso, mas nenhuma nos pisos superior ou inferior, acrescentando que a porta tinha cerca de 1,80 m de largura. *

O colapso e o incêndio

Com o fim do período de apostas e a aproximação dos cavalos à meta, a última coisa que se esperava era o caos e o terror que estavam prestes a desenrolar-se. Um repórter do Hong Kong Daily Press fez o seguinte relato de uma testemunha ocular:

Faltando poucos minutos para as três horas, logo após o terceiro toque da campainha para a primeira corrida..., toda a fileira de tendas e abrigos chineses... desmoronou-se, e uma confusão terrível instalou-se... As tendas caíram gradualmente... caindo... para fora... e fazendo um som como o raspar de uma serra. Parecia que o topo de todas as tendas tinha sido ligado por um fio... e que... tinha sido puxado gradualmente. As tendas e barracas demoraram cerca de 10 segundos a desabar. *

Aureliano Jorge deve ter chegado mesmo na altura em que a corrida da tarde estava prestes a começar. Bernardino estimou que provavelmente desembarcou no ponto de elétrico de Happy Valley com o resto da multidão e correu para fazer as suas únicas apostas naquele dia. Aureliano, então, terá sido um dos primeiros a passar para a frente de um barracão de passadeiras quando a corrida começou, e pode ter sido um dos primeiros a cair no meio da multidão.

Como testemunha do desastre, Bernardino descreveu as bancadas a desabar uma a uma em direção à pista de corrida, como “relva alta a ser derrubada por uma forte rajada de vento”. Nesse momento, ele e outros miúdos aperceberam-se do perigo e rapidamente desceram de uma das bancadas e correram pela pista em segurança.

Aproximadamente ao mesmo tempo, John Olson estava no balcão de bebidas da banca nº 6, aguardando o sinal que assinalava o fim das apostas. Mais tarde, afirmou ter ouvido um estalido na direção do nº 7 e visto uma parte da parede desabar sobre a sua própria bancada, enquanto mulheres e crianças caíam dela. Olson baixou-se sob o seu próprio balcão reforçado no momento em que as paredes do seu stand desabavam à sua volta, evitando ser esmagado. Saiu rapidamente pela frente da bancada, mas ouviu o grito de um rapazinho português, cuja perna estava presa na passadeira. Olson puxou-o para fora, mas foi ferido por uma estaca de bambu que caiu e teve de ser resgatado por um transeunte. *

O agente J. Deskin, que estava na bancada de Olson “a auxiliar na disputa mútua”, testemunhou posteriormente que a divisória entre as bancadas nº 6 de Olson e nº 7 de Xavier oscilou para a frente e para trás no momento em que o pânico começou. Deskin testemunhou então uma debandada de pessoas em direção à saída enquanto decorria o desabamento. O polícia foi projetado para a frente no meio do impacto, mas escapou para a pista de corrida antes de o fogo deflagrar. *

O intervalo entre o desabamento e o incêndio foi notado pelo repórter do Daily Press. Escreveu que parecia que aqueles que tinham caído das bancadas estariam seguros, uma vez que alguns estavam a abrir buracos no teto de lona para escapar. Mas, de repente, fumo branco e chamas surgiram nas laterais das bancadas e começaram a alastrar.

As chamas foram vistas a subir de um dos barracões e rapidamente se espalharam por todo o local... À medida que as chamas rugiam, o vento intensificou-se e o calor tornou-se insuportável. ... Houve uma terrível aglomeração, todos lutaram para se salvar. ... O surto causou um pânico terrível... e centenas foram atirados ao chão, os quais, de outra forma, não teriam tido dificuldade... em escapar... Uma vez lá embaixo, o caso... acabou. As nuvens de fumo... devem ter sufocado muitos. ... Crianças foram arrastadas para aqui... e temo que várias delas tenham morrido espezinhadas... *

Testemunhas oculares relataram que Ludovino Xavier e a sobrinha Daria estavam sentados com outros familiares na bancada nº 7. * Quando o tapete colapsou, Daria ficou presa sob pesadas varas de bambu. De seguida, os tambores do piso inferior pegaram fogo e rapidamente engoliram a estrutura.

O irmão de Daria, Paulo, e outros tentaram libertá-la, mas Paulo sofreu queimaduras graves nos braços na tentativa. Anos mais tarde, Paulo relatou, em lágrimas, como Daria lhe disse que não adiantava e que fugisse para salvar a vida. Paulo ficou ali até ao último momento possível e quase foi apanhado pelas chamas até que um sargento da polícia o puxou para um lugar seguro. Um cadete da polícia portuguesa, identificado apenas como “R. Lopes”, é creditado pelo resgate de vários outros membros da família Xavier.

Quando Bernardino e os seus amigos estavam na pista de corrida, reparou no fumo a subir das bancadas desabadas, seguido imediatamente por incêndios por todos os lados. Em menos de um minuto, escreveu que “milhares” que ficaram presos sob bambus e folhas de palmeira caídas não tiveram tempo de escapar.

Afirmou que aqueles no infield eram…

“… atordoados pela visão impressionante…: um enorme incêndio e fumo a subir a mais de duzentos… pés, acompanhados de… gritos altos vindos de todos os lados. Como éramos jovens na altura, foi certamente uma visão e uma experiência… que ninguém poderia esquecer!”*

Os gritos eram acompanhados por “estalidos” abafados, como a explosão surda de fogo de artifício sob a areia. Um dos homens mais velhos explicou aos rapazes que era o som de crânios a explodir sob o calor intenso.

Ludovino Xavier e Aureliano Jorge tiveram destinos semelhantes. Dizia-se que “Bino” tinha escapado ao desabamento e ao incêndio fugindo para a segurança do hipódromo. Mas, de repente, apercebeu-se que tinha deixado para trás o cofre na casa de apostas da família. Correndo de volta para as chamas, ficou também preso nos escombros e juntou-se às outras vítimas. O corpo de Aureliano foi identificado por Carlos após uma longa busca. Embora queimado ao ponto de se tornar irreconhecível, Carlos estava convencido de que era seu amigo quando o relógio de ouro de Aureliano foi encontrado debaixo do seu corpo.

As consequências

Um inquérito do governo de Hong Kong registou oficialmente 670 mortos, a maioria mulheres e crianças chinesas, com centenas de feridos e vários corpos não identificados. O número exato de mortos e as suas etnias nunca foram totalmente contabilizados. * Com base em registos fornecidos pelo site Macanese Families e outras fontes, pelo menos nove macaenses morreram no incêndio e vários outros ficaram provavelmente feridos. Maria Ernestina Vieira RibeiroNo site restrito, clique no ícone PESQUISAR e digite o seu número (1525) para ser levado para a sua página’], José Libânio Manuel Spencer do Rosário, Gustavo Maria do Rosário, Carlota Isabel Vieira Ribeiro, Maria Amélia Vieira Ribeiro, Ludovino Leopoldo Xavier, Daria Maria Xavier, Aureliano Guterres Jorge, e Luís Gonzaga Baptista. Entre os feridos estavam o Sr. e a Sra. J. Remédios. Há também relatos, não confirmados, de que membros da família d’Aquino estariam entre os mortos. (Correspondência de Fredric “Jim” Silva ao autor, 8 de abril de 2012.)

Poucas semanas depois, a comunidade portuguesa reuniu-se no Clube Lusitano, em Hong Kong, para expressar as condolências às famílias e familiares das vítimas. Muitos agradeceram as demonstrações de solidariedade dos dirigentes militares, governamentais e religiosos, que incluíram a oferta de alojamento e educação gratuitos aos filhos de Ludovino Xavier no Seminário de Macau. *

As missas de requiem foram celebradas pelas vítimas macaenses em Hong Kong, Macau e outras cidades chinesas. Um correspondente na cerimónia em Cantão escreveu que quase todos os membros da comunidade portuguesa compareceram, acrescentando:

… o serviço foi mais do que uma expressão convencional de simpatia. Foi, de facto, uma manifestação exterior de genuíno pesar, não só pelos familiares e amigos… mas também pelas centenas de seres humanos que foram vítimas de uma terrível catástrofe. *

Logo surgiram recriminações no seio do governo de Hong Kong. O médico legista de Hong Kong observou que:

Um membro do Conselho Legislativo destacou ainda:

“… esta calamidade… poderia provavelmente ter sido evitada pelo exercício da previsão… esperada antes do evento…”

“… negligências e omissões de dever por parte do Departamento de Obras Públicas (a agência de licenciamento das bancadas) e do Departamento de Polícia (que supervisionava o Corpo de Bombeiros de Hong Kong).”*

Isto levou o governador, Sir Francis Henry May, um entusiasta das corridas de cavalos, * a assumir a responsabilidade oficial pelo incêndio, expressando sentimentos que muitos provavelmente partilhavam:

Culpo-me pela falta de precauções contra incêndios, porque fui chefe de polícia aqui durante nove anos e nunca previ um incêndio nestes barracões. *

Depois, para seu crédito, o Governador proibiu permanentemente o uso de bancadas temporárias no hipódromo. * A construção de novas bancadas começou logo de seguida.

A decisão e as reformas chegaram tarde demais para as vítimas do incêndio de Happy Valley em 1918. As memórias desse dia apagaram-se, juntamente com um memorial solitário erguido em 1922 atrás do antigo hipódromo.

As corridas de cavalos continuam em Happy Valley, onde a emoção da temporada atrai milhares de pessoas todos os anos. Mas, com o passar do tempo, talvez os fantasmas da tragédia do hipódromo, representando os muitos grupos étnicos que estiveram presentes nas bancadas naquele dia, possam agora descansar um pouco mais descansados sabendo que a sua história foi finalmente contada.