'An Unexampled Calamity'

The Hong Kong Plague of 1894

by Stuart Braga

Article originally published in Casa de Macau Australia Bulletin

He meant that there was no other example of so great a calamity. The calamity was a serious outbreak of bubonic plague, which brought Hong Kong to its knees. Strangely, although it also devastated Canton, it left Macau largely intact. Sir William might have added that it was a vast human tragedy as well, for several thousand people, mostly poor Chinese, died, and more than 100,000 fled in panic to their home villages.

It appears that before the disease reached Hong Kong it had broken out in Canton in January that year, and by June it had accounted for some 80,000 deaths. Rapidly moving down-river, it first appeared in the Tai Ping Shan district in the early months of 1894. At that time, Tai Ping Shan, high above Kennedy Town to the west of Hong Kongs Central District, was a crowded squalid settlement of Chinese workers. There was no water supply or sanitation, and living conditions were utterly filthy.

In Tai Ping Shan there was panic and hysteria, for the outcome in the great majority of cases was an agonising death after three days of suffering. A graphic description of the symptoms of bubonic plague was given by M. Wilm in his Report of Plague in Hong Kong compiled in 1896. Wilm observed that

“at the outset of the disease the tongue usually became swollen, bright red at the tip and edges and was covered with a greyish white fur. Usually, on the second or third day of the disease, the fur became brownish or black, and dried in a crust. The tongue becomes cracked and fissured … The lips soon became dry and often fissured, the mucous membrane of the mouth and the pharynx was usually bright red. The appetite disappeared. There was frequently uncontrollable vomiting and great thirst.”

He goes on, but the details are too distressing to relate here.

On 10th May 1894 Hong Kong was declared an infected port and within the space of a few weeks the administration was faced with an epidemic of great magnitude. By July there had been 2442 deaths. Hospitals were quickly established on board the naval ship, Hygeia, at Kennedy Town Police Station and at the Kennedy Town glass works. The first two were run by European staff whilst the third was manned by Chinese personnel of the Tung Wah hospital. The Governor told his superior in London that ‘it was deemed advisable to give the Chinese doctors a free hand at first. In any case, it is difficult to persuade the Chinese to report cases of sickness and their foolish and violent prejudice against Western medical men is quite sufficient to induce them, as they certainly did for the first fortnight or three weeks of the existence of the plague, not only to secrete their sick but often to desert their plague-stricken friends and relations after death.

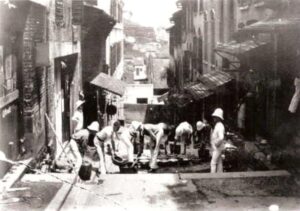

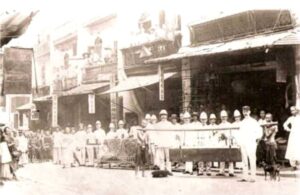

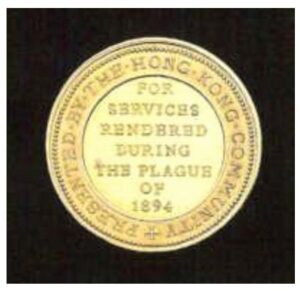

The army was sent in to cleanse and disinfect the fetid slums and to collect the dead. The 1st Battalion of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry was stationed in Hong Kong at the time, and when the plague broke out, volunteers were called for to work on plague relief. About 600 of the 1,000 men did so. The unit history tells us that ‘the work was unpleasant in the extreme – searching narrow backstreets and overcrowded houses for plague victims, tending the sick in makeshift isolation hospitals and disinfecting the houses and streets with chloride of lime and whitewash. One of the most unpleasant tasks faced by the volunteers was the location and removal of the dead, searching dark houses and carrying away the bodies to be buried in mass graves. The volunteers of the KSLI lived in quarantine in separate tented camps and were given extra rum rations to help them cope with the work. Remarkably, only one officer and nine men of the regiment fell ill and only two actually died of the plague.

The soldiers found unimaginable horrors. They were on one occasion accompanied by a 28-year-old Scottish doctor, James Lowson, Acting Superintendent of the Civil Hospital. He wrote, ‘On a miserable sodden matting soaked with abominations there were four forms stretched out. One was dead, the tongue black and protruding. The next had the muscular twitchings and semi-comatose condition heralding dissolution. Another sufferer, a female child about ten years old, lay in accumulated filth of apparently two or three days. The fourth was wildly delirious.When the disinfection of houses was undertaken it was the usual practice for the occupants to be issued with new clothes. Their own clothes, bedding, curtains and carpets were sent to a steam disinfecting station. The premises were then thoroughly cleaned by spraying the walls with a solution of perchloride of mercury; alternatively, rooms were fumigated with free chlorine obtained by the addition of diluted sulphuric acid to chlorinated lime. Finally, the floors and furniture were scrubbed with Jeyes fluid, a well-known disinfectant, and the walls were lime-washed. During these operations the occupants were given temporary accommodation on Chinese marriage boats anchored in the harbour off Stonecutters Island.

Other measures taken included the burial of the dead in a plague cemetery at Kennedy Town and the regular disinfecting of all public latrines with chlorinated lime.

The soldiers who carried out these draconian measures were resisted fiercely, and the papers spoke of ‘plague riots. Violent mobs prevented the removal of patients with plague from the Tung Wah Hospital to a special plague hospital, doctors had to carry pistols, and a gunboat was needed to restore order. Placards were posted in Hong Kong and Canton accusing the English doctors of cutting open pregnant women and scooping out the eyes of children in order to make medicines for the treatment of plague victims. Race relations in Hong Kong plunged to a new low; this was a crisis of public health, public order and soon, an economic crisis as well, as ships stopped entering a port that relied on trade for its existence.

Whole blocks of Tai Ping Shan were torn down and rebuilt with proper drainage and better ventilation. This picture was taken in 1898, four years after the plague struck.

The Sanitary Board met often and Lowsons diary reveals that tensions were high. At one meeting, he told two Board members ‘they were both damned cowards as they were afraid to go to the plague areas. He comments ‘Lockhart [the Registrar General] and Governor are now making themselves obnoxious — Bl [bloody] fools. They are walking into the mire properly. His report was later described as ‘an egotistical and garrulous document, written by someone who ‘evidently wants to make a name for himself.

In autumn, the plague subsided, and things calmed down for a time, but for several years it became an almost annual occurrence usually making its appearance in February or March reaching a peak by July and then virtually disappearing during the autumn and winter. Over the period 1894-1901 some 8,600 persons succumbed to the disease and this represented a mortality rate of about 95 per cent of those affected.