The great typhoon of 1874

by Stuart Braga

Edited version of an article published in the Casa Down Under Newsletter, vol 20 Issue 4, Sept 2008

A grande calamidade. So begins the report of the session of the Leal Senado (the Macau Council) of 29 September 1874, quoted by the prolific Macau historian, Father Manuel Teixeira 1 . Writing in 1974 on the centenary of the typhoon, Teixeira described it as the most destructive ever experienced in the history of Macau. As cyclones are to Northern Australia and hurricanes to the southern United States, so typhoons are to the South China Coast. Over the centuries they have brought death and disaster on a huge scale. The horroroso tufão of 1738 was the greatest disaster to have befallen Macau up to that time. About a century later, two typhoons created havoc only a year apart, in 1847 and 1848. By 1847, meteorological records had commenced, and the mercury dropped to 745 mm. The following July, another grande e violento tufão swept the coast of South China.

On this occasion, the barometer in Macau dropped to 709mm, the lowest pressure ever recorded at that time in China 2. While Hong Kong endured a terrific battering, Macau was almost obliterated. C.A. Montalto de Jesus, then a boy of eleven living in nearby Hong Kong, wrote about it a quarter of a century later.3

‘As if nature too were bent on the downfall of Macao, a terrific typhoon, its very centre, swept over the ill-fated colony on the memorable 22nd of September 1874; and a fateful shift of the wind from north to east, at the equinoctial spring tide doomed the fairest part of the city to the full havoc of cyclonic blasts and waves. Battered, flooded, Macao was at the same time assailed by pirates.’

‘the lurid glare revealed many an imminent peril in that night of unspeakable horror and tribulation.’

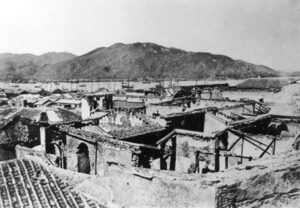

The official report, dated 23 October 1874, lists street by street Chinese houses lost. They totalled 1,172 4. Between 4,000 and 5,000 people died and 2,000 fishing and trading craft were lost. On Taipa more than 1,000 bodies were found and another 500 on Coloane, chiefly of fishermen. The value of houses, goods and ships lost came to roughly $2 million, a vast sum at that time3.On 22 September 1874,

‘It was a very hot and still night and people were out in the Praia Grande in search of a little fresh air. A full moon … filled the night sky. As people began to make their way home, it started to rain heavily and a strong wind started up. Everyone firmly secured and locked their doors and windows … Never had there been such a strong typhoon. The sea level rose so high that a lorcha [a light vessel with a European hull, and the rigging of a Chinese junk] was washed up close to the cathedral.’

The loss of ships in Hong Kong was greater than that in Macau, because the commerce of Macau had diminished during the previous thirty years. The London newspaper The Times reported on 30 September that five ships had been sunk, six were missing, three had run aground and another nine dismasted. (30 September 1874). A week later on 5 October the paper printed another long list of vessels damaged which had struggled back to Hong Kong harbour for repairs. It is interesting to note that the British papers reported only the loss of shipping. There is no mention of loss of lives or property. The British were concerned only with commerce.

Nevertheless, Macau would fulfil a vital role between 1942 and 1945 when more than 10,000 British and American people flocked there during World War II, as a calamity far greater than any typhoon overtook Hong Kong – the Japanese Occupation. If Macau had not been there for these refugees, their situation would have been unimaginably desperate. Macau, abandoned by the British for a century, generously gave them relief and safety in their time of need.

A note on sources. The Macau Collection Room of the Macau Central Library, Av. Conselheiro Ferreira de Almeida, contains all the local sources used. I am grateful to Marie Imelda MacLeod, Directora do Arquivo Histórico, for her assistance in locating printed and photographic sources there. Other printed sources are in the National Library of Australia, notably the JM Braga Collection.

I appreciate also the efforts made by António M. Jorge da Silva in enhancing the photographs.

Stuart Braga